A remarkable discovery in northern Norway has uncovered the remains of 46 species from the last Ice Age — from reindeer and Arctic foxes to whales and seabirds — preserved for 75,000 years inside a mountain cave.

A cave near Kjøpsvik in the municipality of Narvik, northern Norway, has yielded one of the most extraordinary Ice Age fossil finds in Europe. Deep inside the Arne Qvam Cave, scientists uncovered thousands of fragmented bones from animals that once lived there 75,000 years ago — offering a detailed glimpse into a cold, coastal Arctic ecosystem long before the last glaciers reached their maximum.

The research, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), reveals a rare and rich mix of mammals, birds, and fish, making it the oldest preserved faunal assemblage ever found in the European Arctic.

“Unique, even by global standards”

“This is extremely rare and valuable,” says Sanne Boessenkool, professor of evolutionary biology at the University of Oslo and co-author of the study. “Most traces of Ice Age life in Scandinavia were wiped away when glaciers advanced and stripped the land bare. These cave sediments are a remarkable exception.”

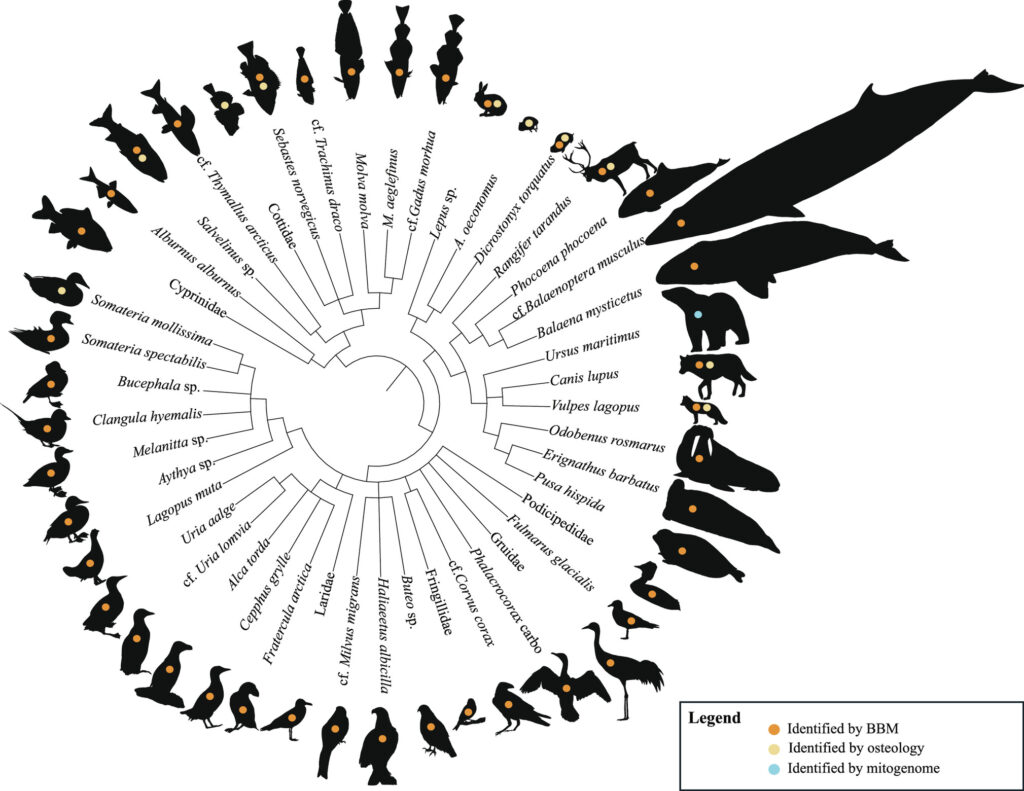

Altogether, the researchers identified 46 animal taxa: 23 bird species, 13 mammals, 10 kinds of fish, and a handful of marine invertebrates and plant remains. Such a broad range of fauna from one Ice Age deposit has never before been found in Scandinavia.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“It’s unique, even by global standards,” Boessenkool says.

A cave frozen in time

The Arne Qvam Cave is part of the larger Storsteinhola karst system, first discovered by chance in the early 1990s during tunnel construction by the cement company Norcem (now Heidelberg Materials). Initial investigations revealed polar-bear bones, but it was not until 2021 – 2022 that a full excavation, funded by the Research Council of Norway and led by Trond Klungseth Lødøen of the University Museum of Bergen, began in earnest.

The team excavated thousands of bone fragments from sediment layers corresponding to a relatively mild interstadial phase of the Ice Age, known as Marine Isotope Stage 5a (roughly 85 – 71 thousand years ago). Despite being buried beneath later glacial deposits, the cave’s higher elevation and unique drainage system protected the sediments from destruction.

Polar bears, whales, and seabirds

Among the finds were bones of polar bears (Ursus maritimus), walruses, ringed and bearded seals, reindeer, and Arctic foxes. The researchers also discovered remains of whales, including blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) and harbor porpoise, as well as cold-water fish such as cod, haddock, and redfish.

Bird bones were abundant too — 23 species in total — ranging from seabirds like ducks, auks, and king eiders to land species such as ravens, cranes, and rock ptarmigans. Together, these species indicate a coastal tundra environment bordered by seasonal sea ice.

“What’s most exciting is the overall picture,” Boessenkool says. “We get a glimpse of a complete Ice Age ecosystem — a mix of tundra, sea-ice, and open water — that we knew almost nothing about before.”

An Arctic landscape with life and open water

The animal remains reveal much about the region’s Ice Age climate. The presence of polar bears, seals, and walruses shows that sea ice existed nearby, yet porpoise bones — from an animal that avoids ice — suggest that the ice was seasonal rather than permanent.

“We also found freshwater fish, which means there must have been rivers and lakes in the area,” Boessenkool notes. “And reindeer need wide, open spaces to migrate — so there were significant ice-free areas along the coast.”

The researchers picture a tundra landscape dotted with sparse pine trees, where glaciers retreated seasonally and wildlife thrived much like in modern-day Svalbard, though slightly farther south.

Many Norwegians assume their country was completely buried in ice throughout the last Ice Age. “That’s not the case,” says Boessenkool. “There were large variations, with warmer intervals when the coast remained habitable.”

DNA metabarcoding unlocks hidden species

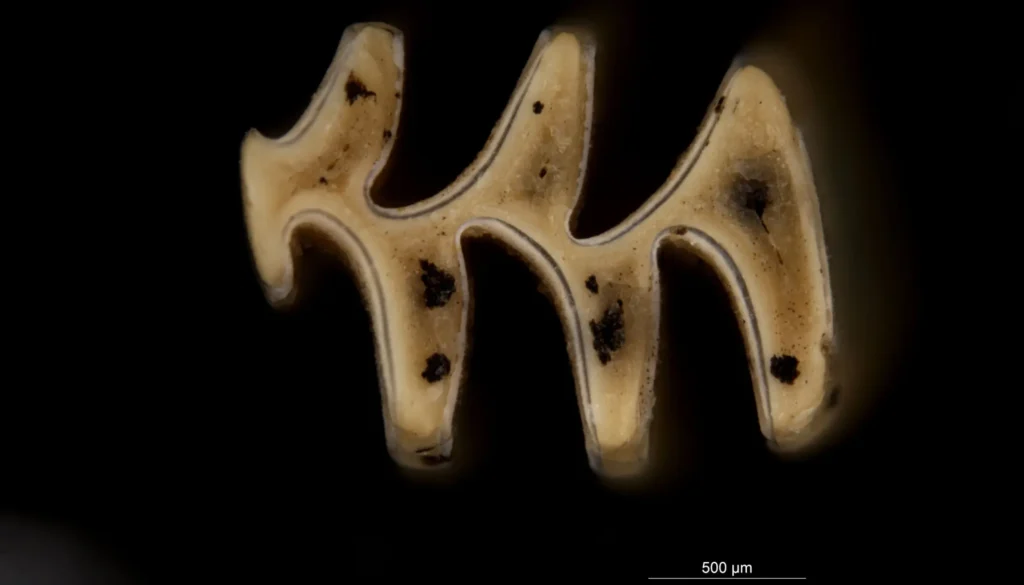

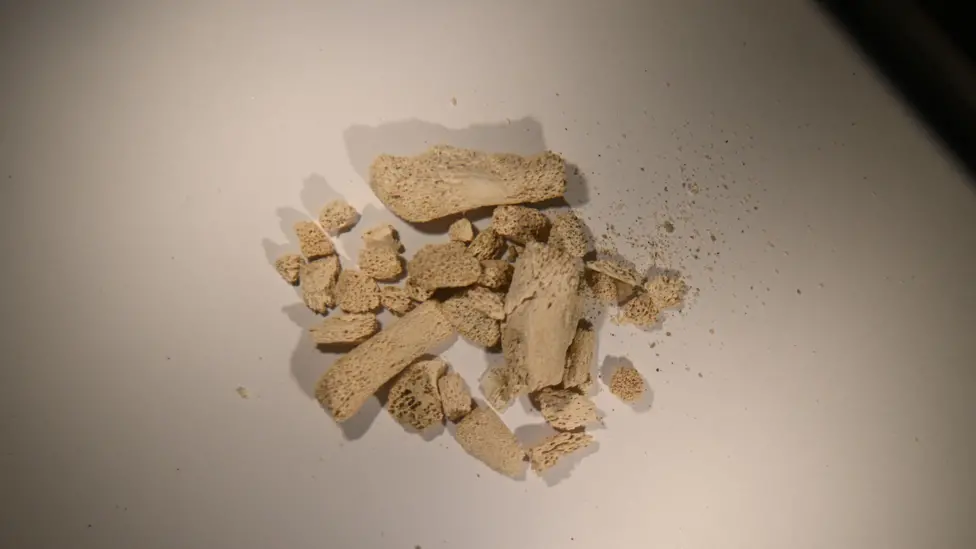

Much of the bone material in the cave was crushed into pieces just a few millimetres long. “We sifted more than a thousand buckets of sediment and used magnifying lamps to extract each fragment,” Boessenkool explains.

Traditional osteology could identify only a small fraction of the fragments. To go further, the team applied DNA barcoding and bulk-bone metabarcoding, methods that extract and analyze traces of DNA from mixed bone fragments.

“These techniques detect short DNA sequences unique to certain species and match them against reference databases,” says Boessenkool. “Thanks to this, we were able to identify far more species — especially birds and fish — than would ever be possible with bones alone.”

According to Hanneke Meijer, a palaeontologist at the University of Bergen not involved in the excavation, this combined approach marks a turning point:

“I’ve worked with cave fossils for decades, and the hardest part is that we usually only find tiny, unrecognizable pieces. Metabarcoding of prehistoric DNA lets us classify those fragments and build a far more detailed picture of past animal life.”

Predators and water: how the bones got there

How did remains ranging from tiny birds to giant whales end up together in one cave? Researchers believe predators and water transport were key. Polar bears and Arctic foxes may have dragged prey into the cave to eat or store, while seasonal meltwater and flooding could have washed in marine carcasses.

The bones show no signs of human activity — no cut marks, burns, or tools — confirming that this was a natural deposit, not a human hunting site.

Extinct lineages and lessons for today

DNA sequencing revealed that several species — including the collared lemming (Dicrostonyx torquatus), Arctic fox, and polar bear — belonged to now-extinct genetic lineages. This suggests that as Ice Age climates shifted, many populations failed to track their habitats and eventually disappeared.

“All the sequenced lineages from the cave are extinct,” says lead author Samuel J. Walker of Bournemouth University. “It shows that Arctic species were resilient in recolonizing the region after glaciations, but they couldn’t always adapt fast enough to survive every major climate swing.”

A window into Arctic resilience

The Arne Qvam Cave site fills a crucial gap in understanding how Arctic ecosystems responded to past climate change. The combination of osteology and ancient DNA analysis reveals a complex, cold-adapted coastal community that thrived during a warmer interlude of the Ice Age — a reminder of both nature’s resilience and its fragility.

“This research connects the past to the present,” says Boessenkool. “By understanding how Arctic species once adapted — or failed to adapt — we gain insight into how today’s wildlife might cope with the rapid warming now transforming the North.”

Walker, S. J., Boilard, A., Henriksen, M., Lord, E., Robu, M., Buylaert, J. P., … & Boessenkool, S. (2025). A 75,000-year-old Scandinavian Arctic cave deposit reveals past faunal diversity and paleoenvironment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), 122(32), e2415008122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2415008122

Cover Image Credit: The sediment profile in Arne Qvamgrotta after excavation. Credit: Trond Klungseth Lodoen/Bournemouth University/PA Wire