In a discovery that may represent the world’s oldest ritual honey, researchers have identified the chemical remains of ancient honey preserved inside bronze jars buried beneath a 2,500-year-old Italian temple once dedicated to a forgotten Greek deity.

New biomolecular analysis reveals that bronze jars from a 6th-century BCE Greek shrine in Italy once contained honey — offering fresh insight into ancient rituals and beekeeping.

Ancient Honey Discovered in 2,500-Year-Old Greek Shrine

In a remarkable breakthrough combining archaeology and modern chemistry, scientists have confirmed that mysterious residues found in bronze jars in an ancient Greek shrine are the 2,500-year-old remains of honey. This discovery, recently published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, is rewriting our understanding of ancient Mediterranean rituals and food practices.

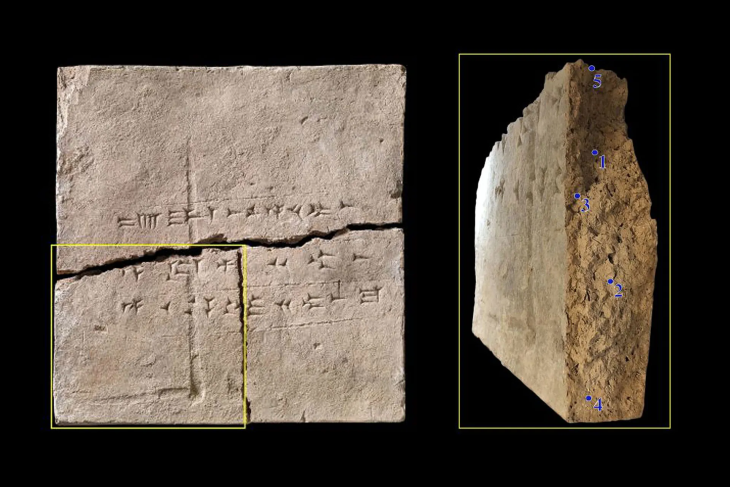

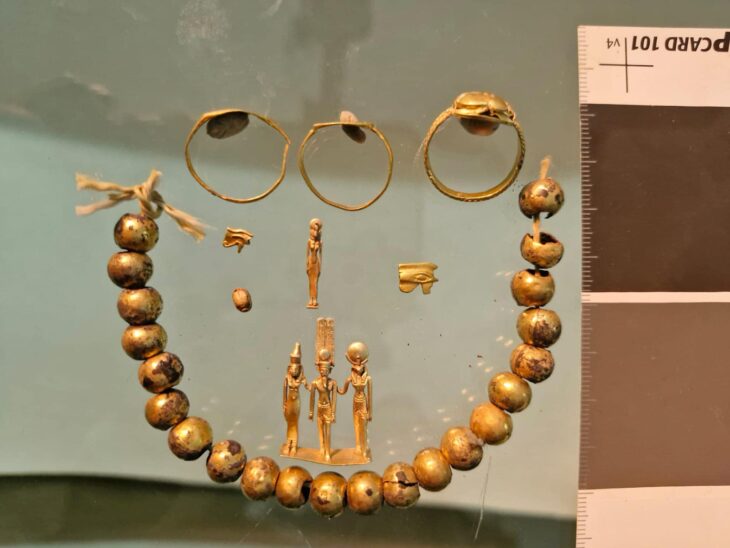

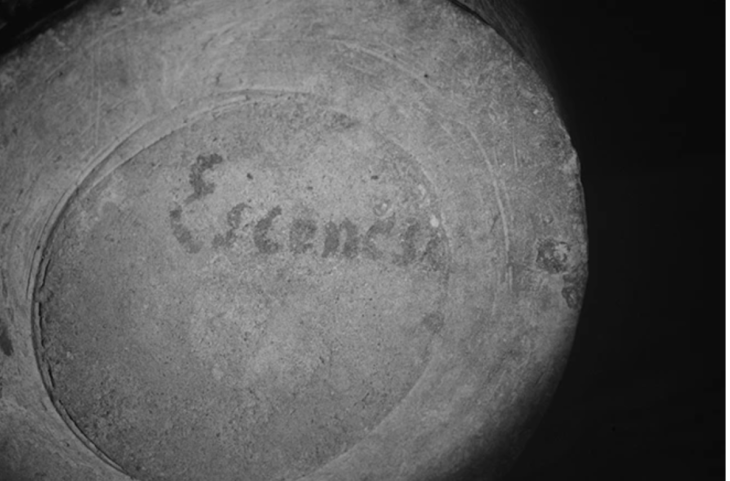

The jars were excavated in 1954 from an underground shrine in Paestum, Italy, a former Greek colony located near modern-day Naples. Inside the shrine were several bronze hydriae and amphorae — ceremonial vessels — containing a sticky, waxy paste. At the time, archaeologists believed the substance might have been honey offered to the gods, yet decades of scientific testing failed to confirm this hypothesis. Until now.

High-Tech Analysis Reveals the Truth

Now, with the help of cutting-edge mass spectrometry, infrared spectroscopy, and proteomic analysis, a research team led by Dr. Luciana da Costa Carvalho and Dr. James McCullagh of the University of Oxford has confirmed the presence of hexose sugars, royal jelly proteins, and other biomarkers uniquely associated with Apis mellifera — the western honeybee.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“Ancient residues are more than culinary scraps — they’re biochemical time capsules,” said Dr. da Costa Carvalho. What we found is molecular evidence that strongly supports the original idea — these vessels once contained real honey. The detection of honey changes how we understand ritual practices in the Mediterranean world.”

Using a multi-analytical approach, the team discovered:

Hexose sugars, a hallmark of natural honey

Saccharide degradation compounds, such as 5-methylfurfural

Royal jelly proteins specific to Apis mellifera (the Western honeybee)

An acidic chemical profile matching the degradation pattern of ancient honey and beeswax

Copper-sugar compounds formed where the honey interacted with the bronze vessels

The team compared these ancient residues with modern samples of beeswax, raw honey, and honeycombs sourced from Italy and Greece, including aged samples to simulate long-term storage. The results were unmistakable — chemically, the 6th-century BCE residue was most similar to a degraded form of honey.

Honey: A Sacred Symbol in the Ancient World

Honey was more than a sweet treat for ancient civilizations. In Greek mythology, honey was a symbol of immortality and divine nourishment, believed to have been fed to infant Zeus. The presence of honey in a religious context — sealed in jars and buried beneath an inaccessible shrine — suggests it was likely part of ritual offerings.

The shrine itself was found with an empty iron bed, further hinting at ceremonial practices tied to death, rebirth, or divine presence.

“This wasn’t food storage. This was sacred,” explains co-author Kelly Domoney from the Ashmolean Museum, which currently houses the residue.

A New Chapter in Archaeological Science

What sets this study apart is not only the discovery of honey, but the innovative methods used to confirm it. Unlike earlier analyses from the 1960s to 1980s, which could only identify fatty acids and wax-like substances, the current research utilized:

Thermal Separation GC-MS to reveal volatile compounds

Ion Chromatography-MS for detecting sugars and acids

Bottom-up proteomics for identifying bee-specific proteins

These tools enabled researchers to distinguish honey from other possibilities like animal fats, resins, or plant oils, which had long clouded previous interpretations.

This study now serves as a benchmark for future residue analysis, especially of museum-held artifacts that were previously considered chemically inaccessible.

This rediscovery of honey in ancient Greek jars is more than a biochemical breakthrough — it’s a bridge between science and sacred tradition. For the first time in over two millennia, we now know that the shimmering liquid once poured into these ceremonial vessels was indeed honey, preserved by time, ritual, and copper.

The research highlights not just what ancient people valued, but how far science has come in uncovering the invisible stories of the past.

da Costa Carvalho, L., Pires, E., Domoney, K., Zuchtriegel, G., & McCullagh, J. S. O. (2025). A symbol of immortality: Evidence of honey in bronze jars found in a Paestum shrine dating to 530–510 BCE. Journal of the American Chemical Society. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c04888

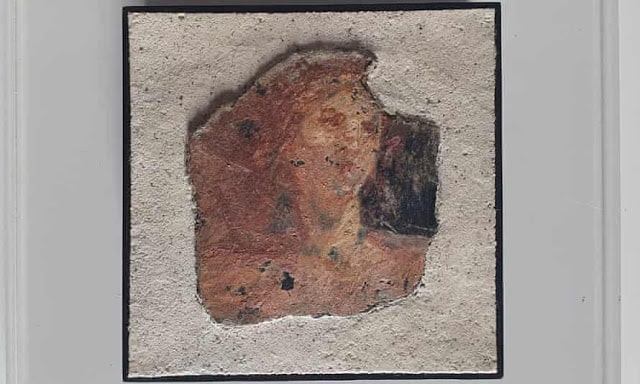

Cover Image credit: This is likely what 2,500-year-old honey looks like, according to new tests using modern techniques. Luciana da Costa Carvalho