For decades, the story of how the first humans reached the Americas has been framed around an inland migration across the frozen plains of Beringia. A growing body of archaeological and genetic evidence, however, is now challenging that long-held narrative. According to a new interdisciplinary study by Japanese and U.S. researchers, the earliest ancestors of Native Americans may have originated not in central Siberia, but in a coastal region spanning Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands—and they may have reached the Americas by sea.

The research, published in Science Advances, proposes that maritime-adapted hunter-gatherers from Northeast Asia played a decisive role in what has been called the final great migration of Homo sapiens.

A Northeast Asian Origin Reconsidered

Paleogenomic studies have long suggested that the population ancestral to Native Americans formed somewhere in Northeast Asia around 25,000 years ago. Genetic data also point to a prolonged period—roughly 4,000 to 5,000 years—of isolation and population decline before these groups entered the American continents after 20,000 years ago. What has remained unclear is where this so-called “standstill” occurred.

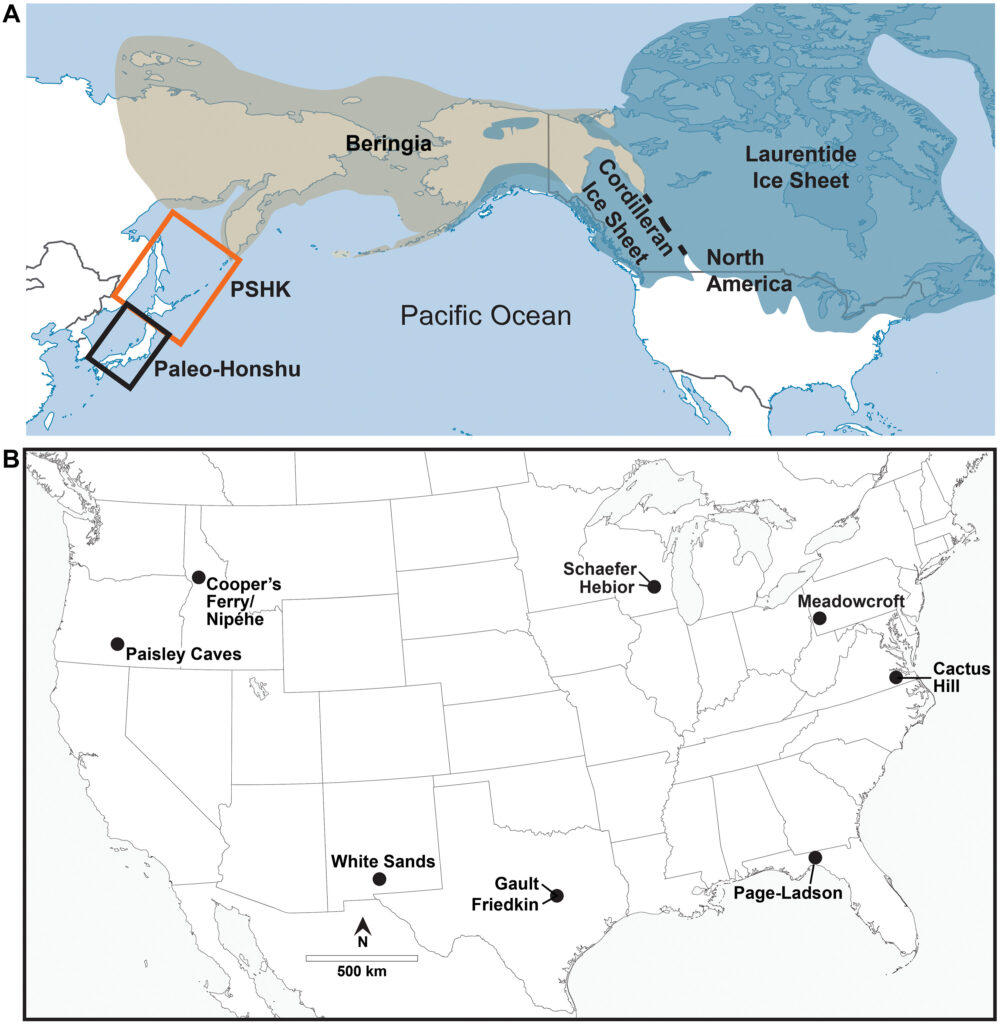

The new study argues that the most plausible location for this prolonged isolation was not the interior of Beringia, but the Hokkaido–Sakhalin–Kuril (HSK) region, which during the Last Glacial Maximum formed an extended peninsula connected to the Asian mainland. Unlike the harsh polar desert conditions of glacial Beringia, this coastal zone offered comparatively stable marine and terrestrial resources.

Stone Tools Tell a Shared Story

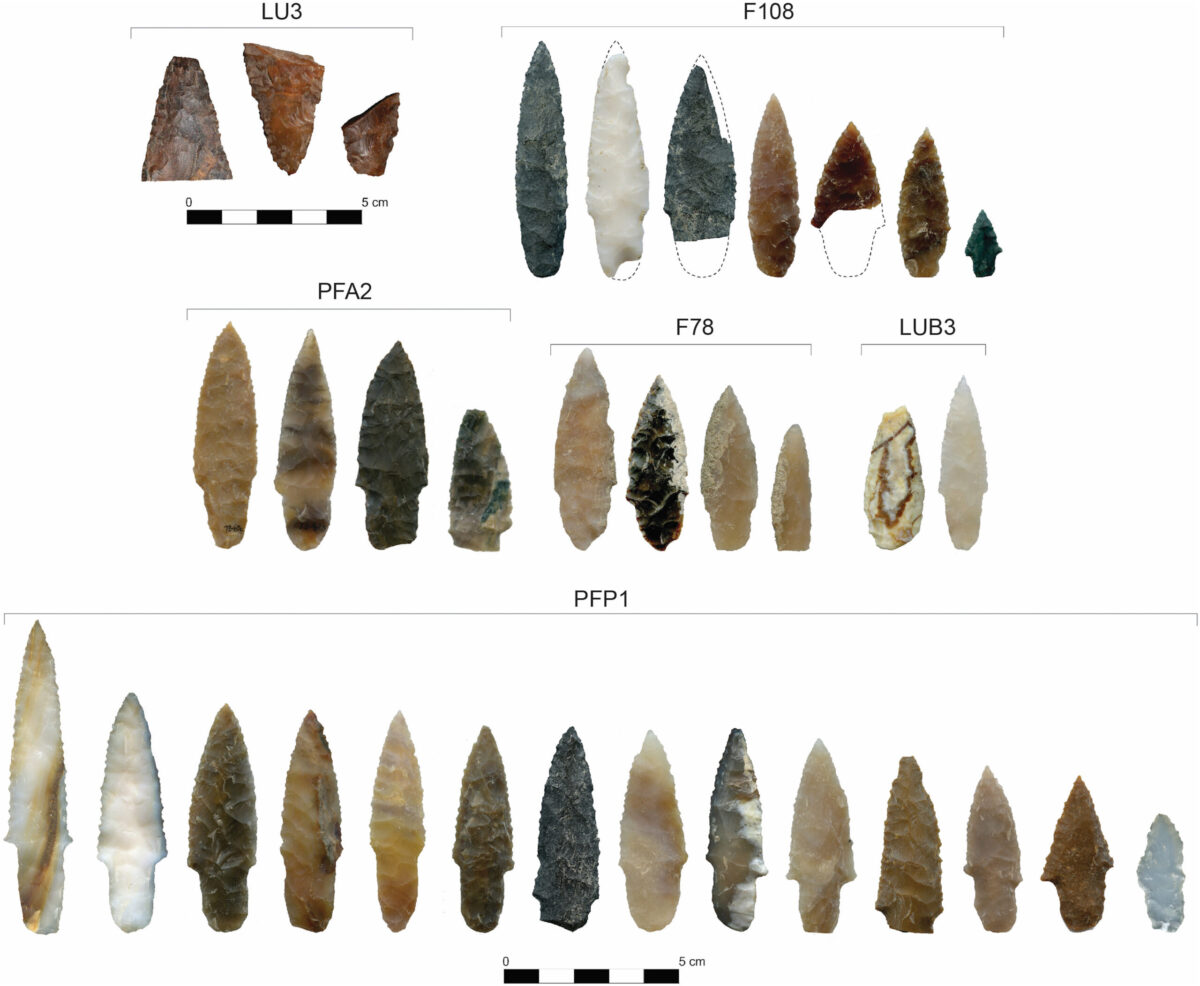

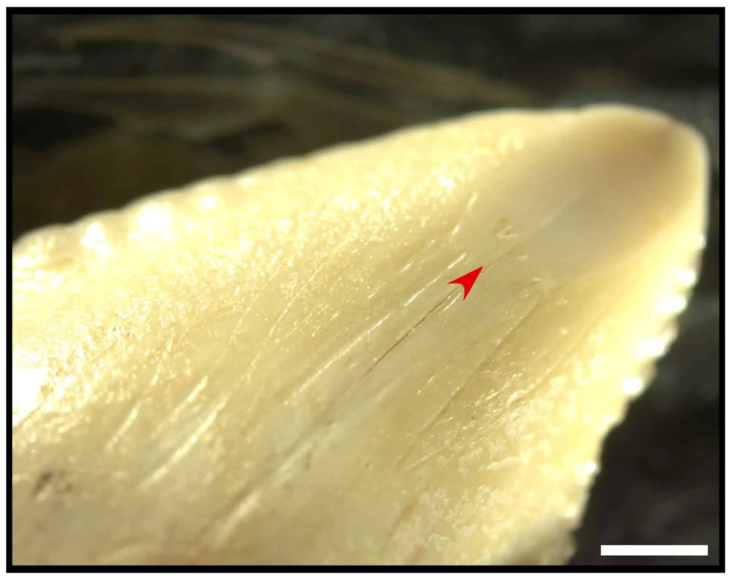

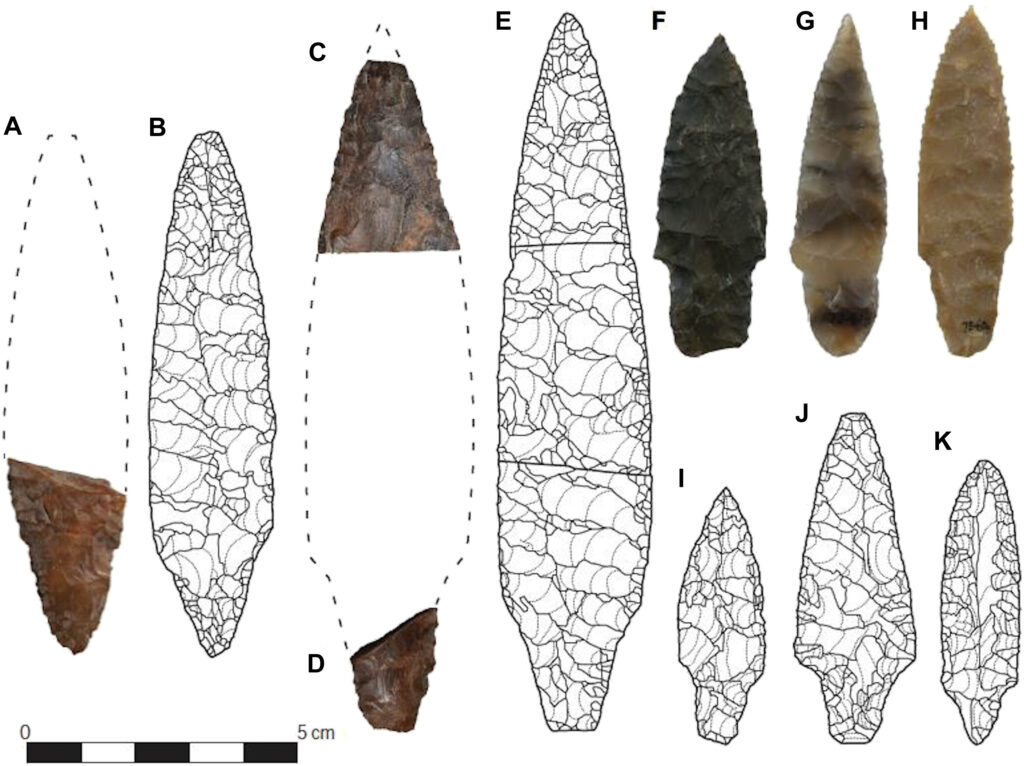

At the heart of the argument lies a detailed technological comparison of stone tools. Researchers analyzed lithic assemblages from ten Upper Paleolithic sites across mainland North America, dated between 18,000 and 13,500 years ago. These sites yielded projectile points and blades with remarkably consistent features: elliptical outlines, sharp bilateral edges, and cross-sections optimized for penetration and durability.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Strikingly similar stone tool designs have been documented at archaeological sites in Hokkaido and neighboring islands, some dating back as far as 20,000 years ago. By contrast, comparable technologies appear in Beringian contexts only around 14,000 years ago. This chronological gap suggests a technological flow from Northeast Asia toward the Americas, rather than the reverse.

Projectile points of this form were highly efficient hunting tools, well suited for both terrestrial mammals and coastal subsistence strategies. Their presence on both sides of the North Pacific points to a shared technological tradition, likely carried by mobile populations with advanced adaptive skills.

Why the Coast Matters

During the coldest phase of the last Ice Age, roughly between 29,000 and 18,000 years ago, massive ice sheets covered much of northern North America. Inland migration routes through Beringia would have been extremely hostile, and notably, no archaeological sites from that period have been found in the region.

In contrast, archaeological evidence from the Japanese archipelago demonstrates that humans possessed seafaring capabilities as early as 35,000 years ago. Sites on islands in present-day Okinawa and southern Kyushu attest to repeated open-water crossings long before the peopling of the Americas.

Building on this evidence, the researchers propose that groups originating in the HSK region followed a circum-Pacific coastal route, moving gradually eastward along shorelines, estuaries, and kelp-rich marine ecosystems. This model aligns closely with the well-known “kelp highway” hypothesis, which argues that coastal environments provided reliable food sources that made long-distance migration feasible even during glacial periods.

A Lost Population in Human History

An important implication of the study is that the HSK population involved in this migration was likely not ancestral to modern Japanese people. Archaeological and genetic evidence indicates that the Jomon populations—often considered among the ancestors of today’s Japanese—entered Hokkaido only around 10,000 years ago.

Instead, the earlier coastal migrants may represent what researchers describe as a “ghost population”: a group that played a critical role in human dispersal but later disappeared or was absorbed without leaving a clear genetic legacy in present-day populations of Northeast Asia.

AUP points from Cooper’s Ferry/Nipéhe LU3 (A, C, D, and F to H) and bifacial stemmed points from Hokkaido (B, E, and I to K). Modified from Davis et al. Credit: Madsen et al., 2025, Science Advances

Rethinking the Final Chapter of Human Expansion

Masami Izuho, an associate professor of archaeology involved in the research, emphasizes that archaeological findings from Japan have often been discussed primarily in a regional context. The new study, he argues, reframes these discoveries as part of a global narrative.

Rather than viewing the peopling of the Americas as a one-directional expansion driven by continental hunters, the findings suggest a more complex process shaped by island-based communities with sophisticated maritime knowledge. Boats, coastal navigation, and marine subsistence may have been as crucial as land bridges and big-game hunting.

Rintaro Ono, a specialist in maritime archaeology, notes that the proposed timeline—slightly earlier than 20,000 years ago—coincides with the coldest climatic conditions of the Ice Age. Resource scarcity, shifts in animal populations, and increasing reliance on marine ecosystems may have pushed these coastal groups to explore new territories across the Pacific Rim.

Implications for Archaeology and Future Research

While the hypothesis does not close the debate on the origins of the first Americans, it significantly strengthens the case for a coastal migration rooted in Northeast Asia. Further archaeological discoveries along submerged coastlines—now hidden beneath post-glacial sea levels—may provide the decisive evidence needed to test this model.

If confirmed, the study would mark a fundamental shift in how archaeologists understand the final stage of Homo sapiens’ global dispersal: not as a desperate crossing of frozen wastelands, but as a calculated expansion by skilled coastal navigators who turned the Pacific shoreline into a migration corridor.

Madsen, D. B., Davis, L. G., Williams, T. J., Izuho, M., & Iizuka, F. (2025). Characterizing the American Upper Palaeolithic. Science Advances, Vol 11, Issue 43. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady954

Cover Image Credit: Madsen et al., 2025