On a quiet rise above the Saale River, long before agriculture reshaped the landscapes of Europe, a woman was laid to rest with an infant in her arms. Her grave—sealed beneath layers of red ochre—remained undisturbed for millennia, a silent archive of ritual practices from a world that vanished nine thousand years ago. Today she is known as the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman, and new microscopic discoveries emerging from her burial are transforming how scholars understand early European ritual life.

The shaman’s story has been told many times since workers first uncovered her grave by accident in 1934. Yet the narrative was always incomplete, shaped by a hurried excavation carried out in a single afternoon. Only recently, as archaeologists returned to the site during redevelopment work in 2019, did it become clear that portions of the original grave had never been touched. Those untouched sediments—lifted in blocks and transported to a laboratory—have now yielded the most intimate details of her ceremonial identity.

What researchers found, under magnification, was something no one expected to survive the passage of nine millennia: microscopic traces of feathers.

A Burial Reopened by Modern Science

The 1934 discovery was dramatic but deeply constrained. With a newly built spa park about to open, archaeologists had mere hours to clear the burial. They saved what they could—antler pieces, animal-tooth pendants, the skeletal remains of a 30- to 40-year-old woman and a six-month-old infant—but much of the surrounding soil was never investigated.

When experts from the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle reopened the site eighty-five years later, they identified surviving pockets of the grave pit still darkened with ochre. These were carefully extracted and subjected to a suite of laboratory techniques unavailable in the early 20th century.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

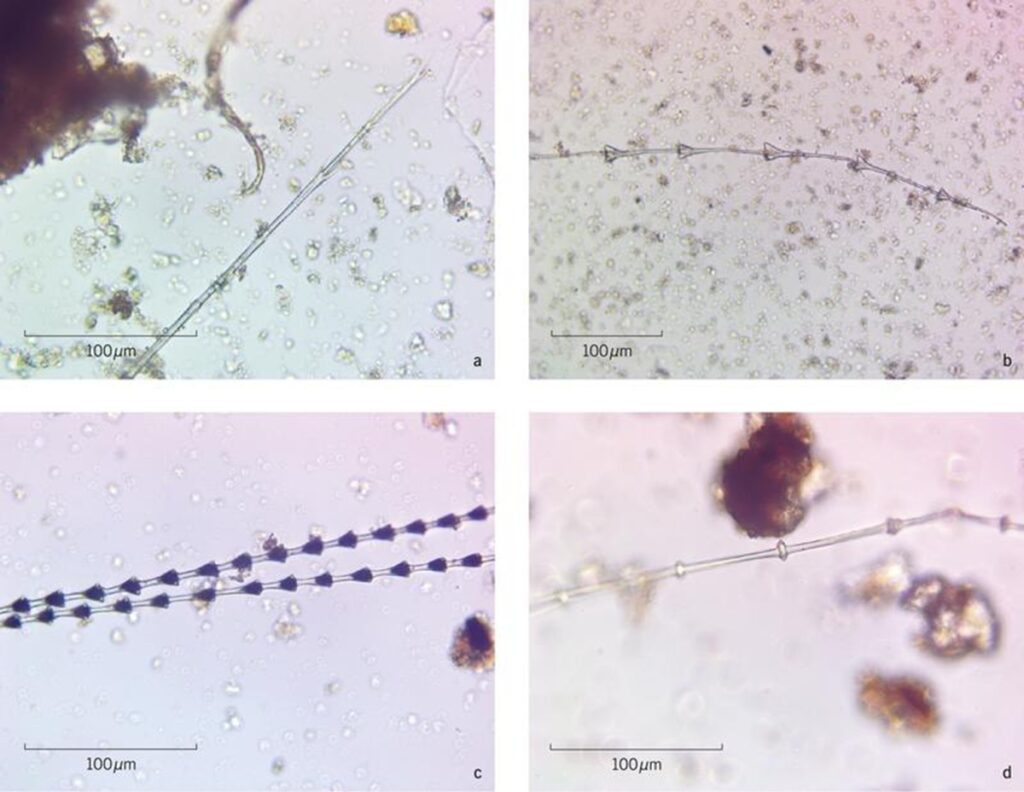

The microscopic work was led by Tuija Kirkinen of the University of Helsinki, a specialist in identifying ancient feather remains. Under high-powered imaging, she isolated tiny hooked structures—some less than a millimetre long—that unmistakably belonged to goose feathers. Their location, clustered around the skull of the deceased, indicates that the shaman once wore an elaborate headdress incorporating feathers, antler elements, and strings of animal teeth.

For decades, reconstructions of the burial depicted such a headdress as a hypothesis rooted in ethnographic parallels. Now, for the first time, scientific evidence has confirmed it.

A Spiritual Specialist in a Transforming World

The Mesolithic epoch—beginning after the last Ice Age and preceding the Neolithic—was a period of profound ecological change. Forests spread across Europe, river systems stabilized, and human groups adapted to more predictable but still challenging environments. Ritual specialists like the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman likely played essential roles in mediating transitions, healing the sick, and negotiating with the spirit world.

Her burial goods reflect this position: a majestic antler structure carefully arranged around her head, strings of animal-tooth pendants that signaled symbolic authority, and layers of red ochre that framed her body in a deliberate ceremonial composition. To these elements we can now add microscopic traces of feathers—an unexpected detail that elevates her identity even further and strengthens the interpretation of her as a spiritual specialist within her community.

The presence of an infant in her arms adds emotional depth, but also cultural complexity—whether the child was her own or a symbolic burial companion remains unknown.

Offerings Left Six Centuries Later

Yet perhaps the most astonishing revelation comes not from the grave itself but from a pit discovered directly in front of it. This feature was created around six hundred years after the shaman’s death, demonstrating a remarkable continuity of memory in Mesolithic communities.

Inside the pit were two ritual masks crafted from red deer antlers. Scientific analysis revealed feather traces on these masks as well—this time from songbirds and grouse-like species, including capercaillie and black grouse. One mask also preserved fragments of bast fibers, hinting that it once formed part of an intricate woven-and-feathered ceremonial costume.

Such long-term veneration is rare in prehistoric Europe. The later offering suggests the shaman’s influence endured across generations, perhaps marking her as a founding ancestor or spiritual patron of the region.

Rewriting the Story of Early European Ritual Life

The convergence of archaeology, microanalysis, and ethnological comparison has turned the Bad Dürrenberg burial into one of the best-studied Mesolithic graves in Central Europe. More importantly, it offers tangible evidence that early hunter-gatherer communities employed sophisticated ceremonial attire—feathered headdresses, an’s grave points to a world rich in symbolism, ritual continuity, and specialized spiritual roles.

Looking Ahead

On 27 March 2026, the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle will open a landmark exhibition, “The Shaman,” dedicated to the Bad Dürrenberg burial and the broader development of ritual practices during the Mesolithic. Featuring major loans from across Europe and the Near East, the exhibition promises to illuminate the earliest roots of religion on the continent.

Nine thousand years after her death, the shaman continues to speak—through bone, ochre, antler, and now the faintest remnants of feathers. Each new discovery draws us closer to a world where ritual specialists shaped the spiritual and social landscapes of early Europe, leaving traces that waited millennia to be found.

Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt (State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt)

Cover Image Credit: Artistic reconstruction of the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman’s ceremonial attire featuring feather adornments. © Karol Schauer | Copyright: State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt