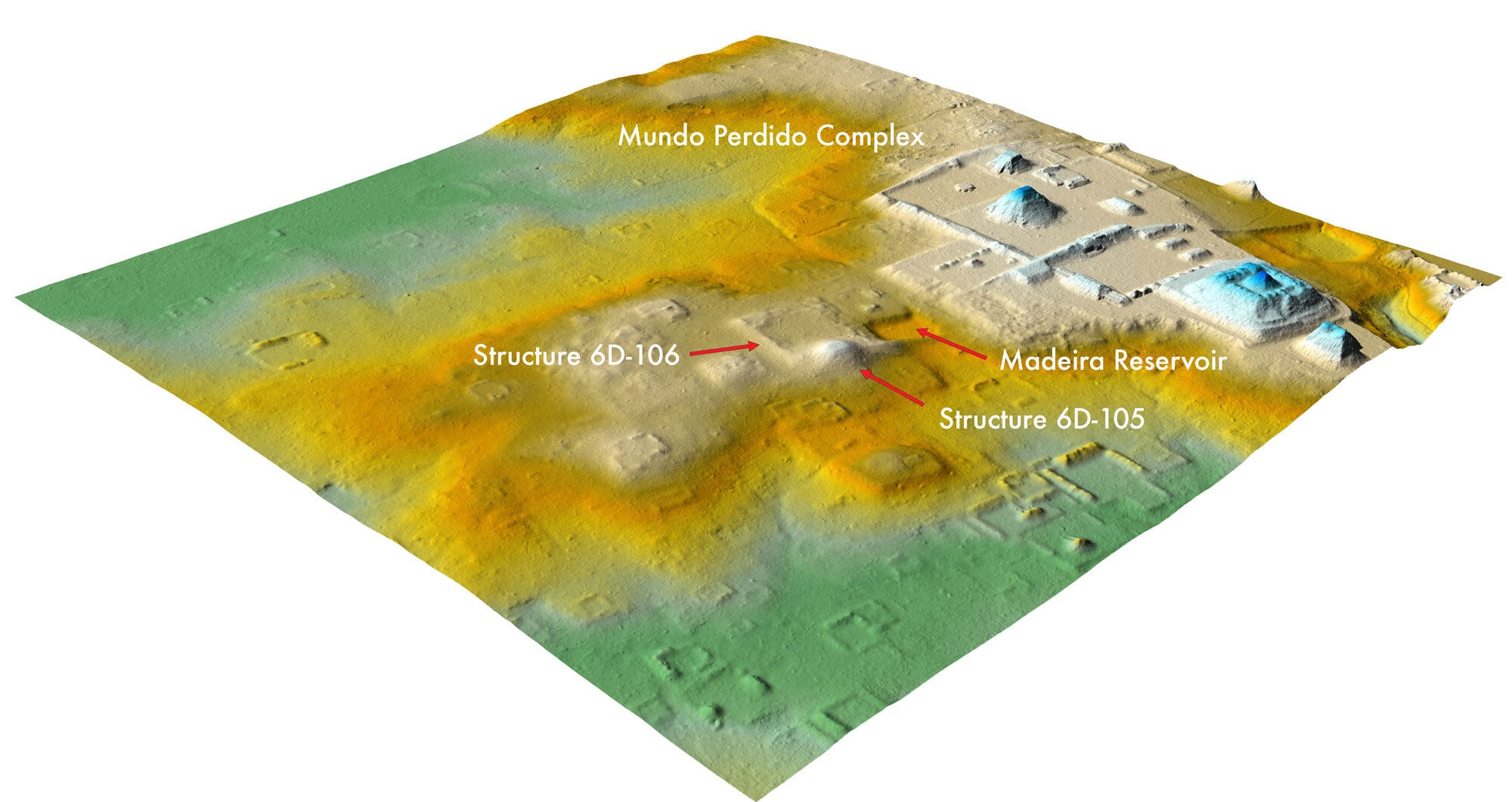

A recent lidar analysis revealed, the region surrounding Central Tikal’s Lost World Complex, which was long thought to be a natural hill, is actually a 1,800-year-old destroyed stronghold.

Scientists have been excavating the ruins of Tikal, an ancient Maya city in modern-day Guatemala, since the 1950s, and Tikal has become one of the world’s best understood and most thoroughly studied archaeological sites as a result of those many decades spent documenting details.

However, a stunning new finding by the Pacunam Lidar Initiative, a research partnership led by a Brown University anthropologist, has ancient Mesoamerican academics all around the world questioning if they know Tikal, as well as they, think.

Using light-sensing and ranging software or lidar, Stephen Houston, professor of anthropology at Brown University, and Thomas Garrison, assistant professor of geography at the University of Texas at Austin, found that what had long been considered the nature area of The Hills at a distance walking distance from downtown Tikal was in fact a neighborhood of ruined buildings that were designed to look like those in Teotihuacan, the largest and most powerful city in ancient Americas.

The results, including lidar images and a summary of excavation findings, was published today (Tuesday, September 28, 2021) in the journal Antiquity.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The lidar research, along with an excavation by a team of Guatemalan archaeologists led by Edwin Román Ramrez, has revealed fresh information and new questions about Teotihuacan’s impact on the Maya civilization.

“What we had taken to be natural hills actually were shown to be modified and conformed to the shape of the citadel — the area that was possibly the imperial palace — at Teotihuacan,” Stephen Houston said. “Regardless of who built this smaller-scale replica and why it shows without a doubt that there was a different level of interaction between Tikal and Teotihuacan than previously believed.”

The cities of Tikal and Teotihuacan were radically different areas, Houston added. Tikal, a Maya city, was fairly populous but relatively small in scale — “you could have walked from one end of the kingdom to the other in a day, maybe two” — while Teotihuacan had all the marks of an empire. Though little is known about the people who founded and governed Teotihuacan, it’s clear that, like the Romans, their influence extended far beyond their metropolitan center: Evidence shows they shaped and colonized countless communities hundreds of miles away.

Houston stated that anthropologists have known for decades that the two towns’ residents were in contact and frequently traded with one another for centuries before Teotihuacan conquered Tikal in 378 A.D.

However, the latest lidar data and excavations by the study team show that the imperial authority in modern-day Mexico did more than merely trade with and culturally impact the smaller city of Tikal before conquering it.

“The architectural complex we found very much appears to have been built for people from Teotihuacan or those under their control. Perhaps it was something like an embassy complex, but when we combine previous research with our latest findings, it suggests something more heavy-handed, like occupation or surveillance. At the very least, it shows an attempt to implant part of a foreign city plan on Tikal” Houston said.

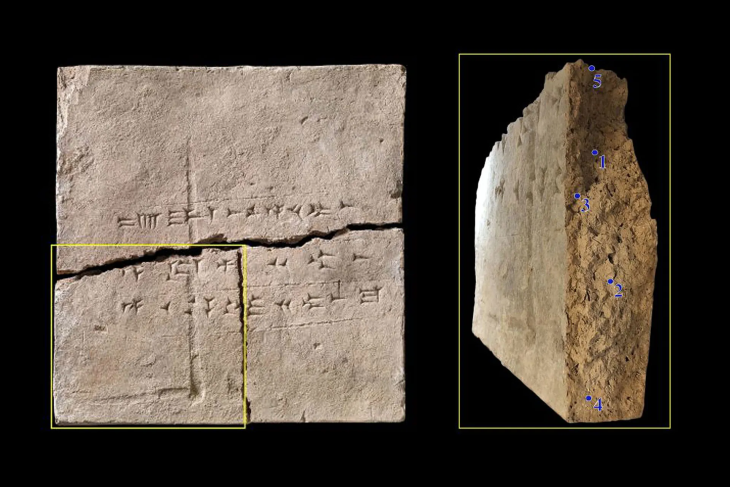

Excavations after the lidar work, directed by Román Ramrez, proved that certain structures were built with mud plaster rather than the typical Maya limestone, according to Houston. The structures were meant to be miniature copies of the buildings that make up Teotihuacan’s citadel, even down to the elaborate cornices and terraces and the complex’s platforms’ unique 15.5-degree east-of-north orientation.

Archaeologists discovered projectile points manufactured with flint, a material typically used by the Maya, and green obsidian, a material commonly used by Teotihuacan inhabitants, at a nearby, freshly unearthed complex of residential structures, providing seeming evidence of conflict.

The consortium’s ongoing research is authorized by the Ministry of Culture and Sports of Guatemala and funded by Guatemala’s PACUNAM Foundation, in partnership with the United States-based Hitz Foundation.