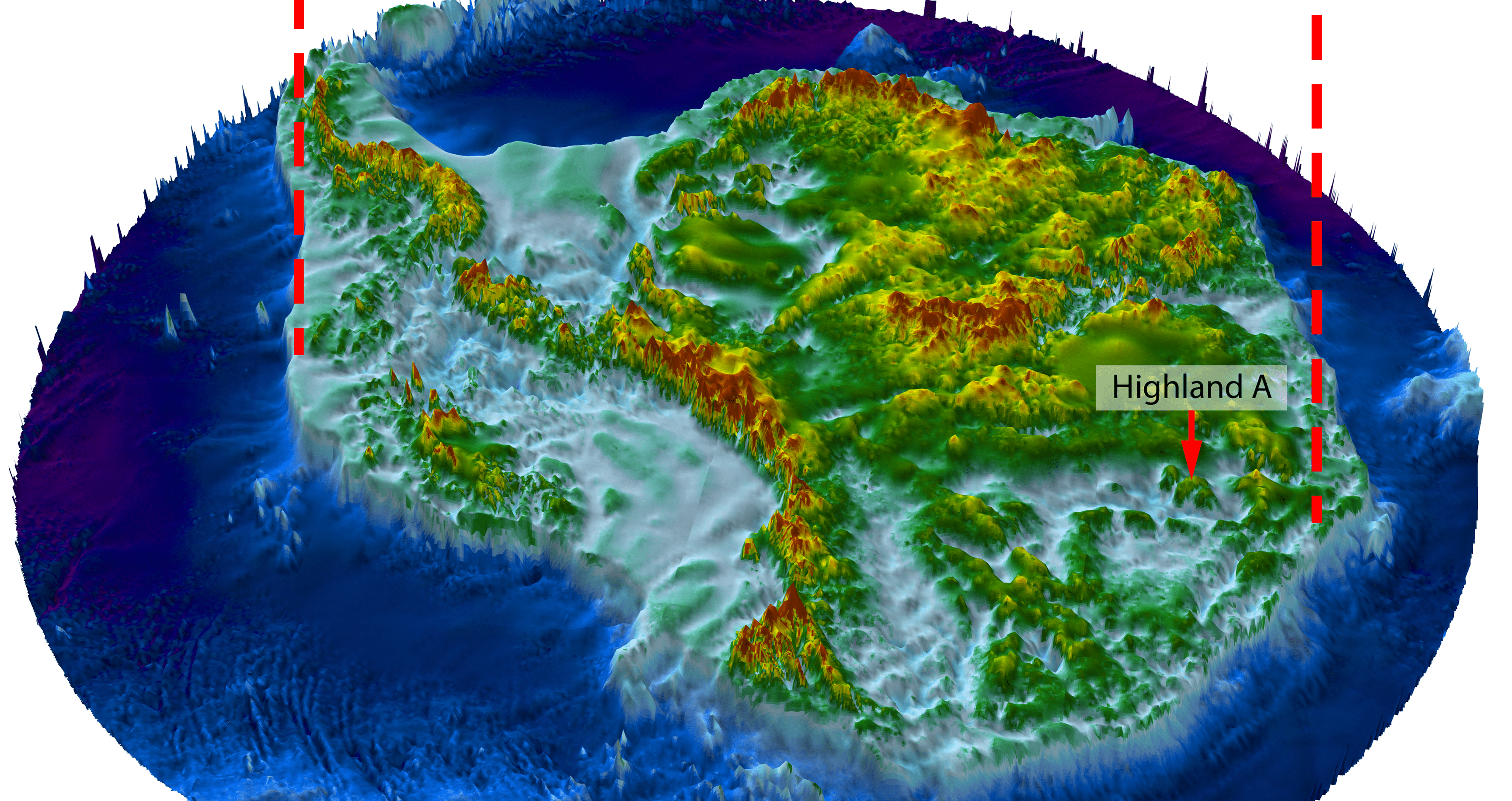

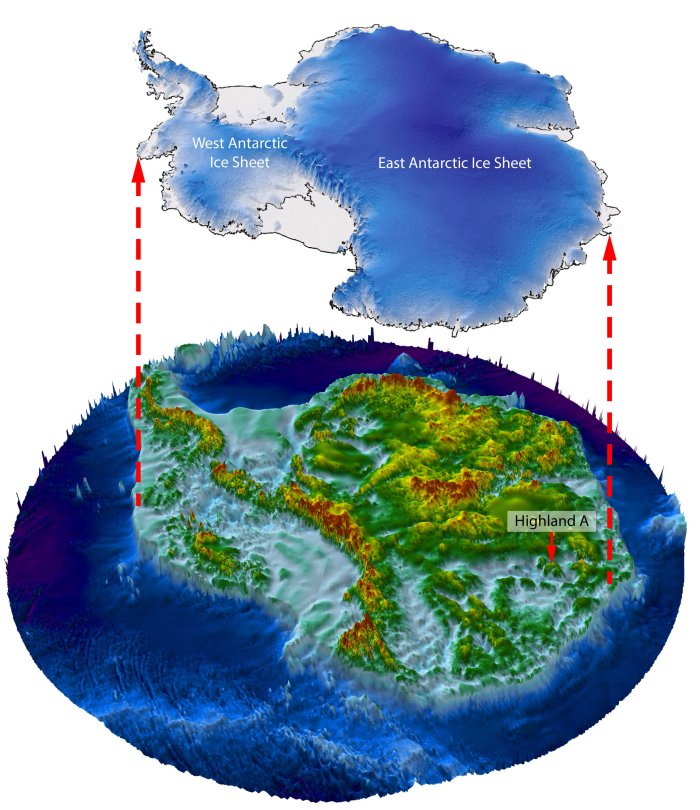

Researchers have uncovered an ancient landscape that remained hidden beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS) for at least 14 million years, using new satellite data and radar imaging.

This newly discovered landscape consists of ancient valleys and ridges, not dissimilar in size and scale to the glacially-modified landscape of North Wales, UK.

With ice-penetrating radar and satellite data, Durham University glaciologist Stewart Jamieson and colleagues mapped the topographic features of the landscape hidden beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet, to get a better understanding of how the ice sheet has fluctuated over time.

The researchers say preserved landscapes like this provide a rare opportunity to examine past ice conditions, but warming temperatures mean we are on track to return to the climate conditions that existed before the landscape was frozen, and it is possible that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet will retreat enough to change the landscape for the first time in at least 14 million years.

“The land underneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is less well known than the surface of Mars,” explained study author Professor Stewart Jamieson in a statement. “And that’s a problem because that landscape controls the way that ice in Antarctica flows, and it controls the way it might respond to past, present and future climate change.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The researchers say preserved landscapes like this provide a rare opportunity to examine past ice conditions, but warming temperatures mean we are on track to return to the climate conditions that existed before the landscape was frozen, and it is possible that the East Antarctic Ice Sheet will retreat enough to change the landscape for the first time in at least 14 million years.

“The land underneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet is less well known than the surface of Mars,” explained study author Professor Stewart Jamieson in a statement. “And that’s a problem because that landscape controls the way that ice in Antarctica flows, and it controls the way it might respond to past, present and future climate change.”

“As ice sheets fluctuate, they modify the landscape upon which they rest, leaving a fingerprint,” the researchers explain in their published paper. “But it is rare to find unmodified landscapes that record past ice conditions.”

The EAIS formed around 34 million years ago when Antarctica iced over and has advanced, retreated, thickened, and thinned, as temperatures fluctuated over geological epochs.

The ice sheet has remained fairly stable for the last 14 million years, covering the vast eastern part of the Antarctic continent, yet the extent of ice sheet retreat during warm intervals remains uncertain.

Scanning the Aurora-Schmidt basins, the team found an ancient landscape 300 kilometers (186 miles) inland from where the present-day ice sheet meets the sea.

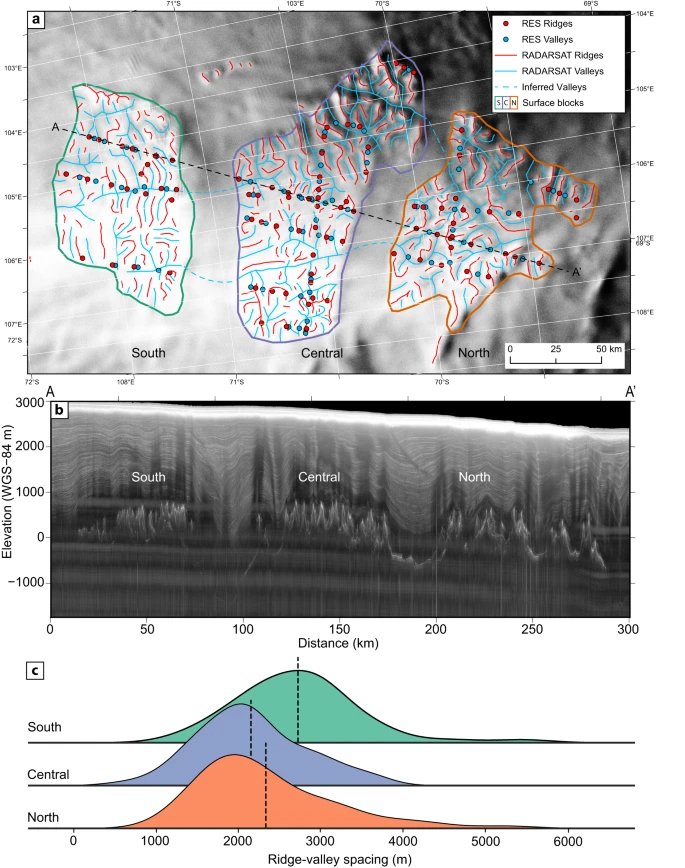

It’s a small part of a vast continent, but a very revealing one. The area consists of three river-carved ‘blocks’ separated by deep troughs about 40 kilometers wide.

An intricate network of ridges and valleys covers the blocks, but these features aren’t consistent with the slow, modern-day northward ice flow across this part of the continent.

So it’s more likely the terrain formed prior to Antarctic glaciation, when rivers crossed the region to a coastline that appeared as the Gondwana supercontinent drifted apart. The researchers suggest the terrain was sculpted from rifts that initially opened up as Gondwana split, which eroded further into deep troughs.

Put together, it suggests this buried landscape likely took shape more than 14 million years ago. Because the network of rivers and valleys is so well preserved, it suggests the region iced over quickly, and that the EAIS hasn’t retreated far enough in the past 14 million years to expose the landscape to other erosive forces, like glaciers.

But ice sheet retreat may reach this region in the future, the researchers warn, if temperatures warm 3-7 °C like they did between 14 and 34 million years ago, when the EAIS formed.

“Given this discovery of an ancient landscape hidden in plain sight, and that of others, we propose that there will be other similar, as yet undiscovered, ancient landscapes beneath the EAIS,” the researchers conclude.

The study has been published in Nature Communications.

Cover Credit: Stewart Jamieson