For nearly two thousand years, a pale earth from the hills of central Italy has quietly bridged the worlds of medicine, craftsmanship, ritual, and science. Today, new archaeological and geochemical research suggests that this humble clay—still sold in local markets—may be the very same substance praised by Pliny the Elder in ancient Rome.

A Clay Worth Writing About

In the 1st century AD, Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder meticulously catalogued the materials that shaped everyday life in the ancient world. Among them was creta umbrica, a pale clay from Umbria prized not for beauty, but for utility. Used by fullers—specialists who cleaned and restored wool garments—this clay had a remarkable ability to absorb grease and revive dulled fabrics.

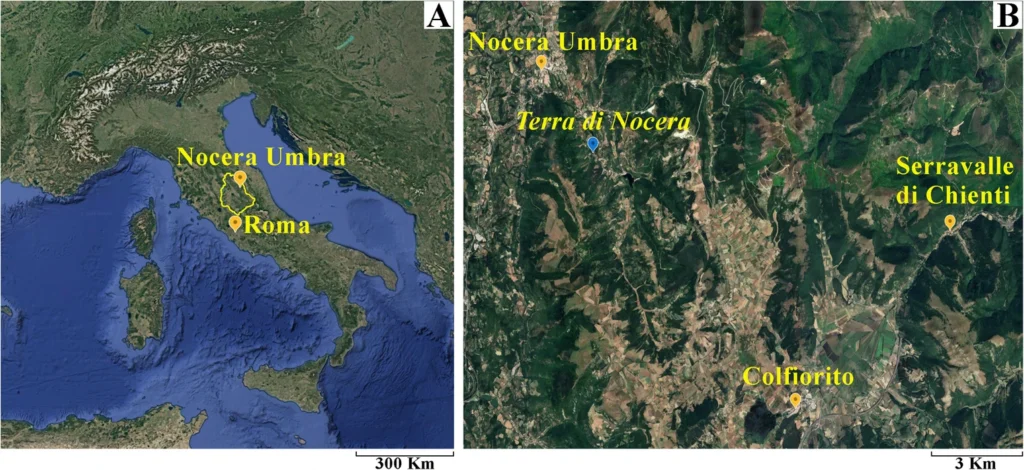

Fast forward to the present, and a similar material still circulates in the same region under a different name: Terra di Nocera. Marketed today for cosmetic and therapeutic purposes, this white clay from Nocera Umbra is used in soaps, skin treatments, and traditional remedies. Could this modern product be the descendant of Pliny’s creta umbrica?

A multidisciplinary research team believes the answer may be yes.

Science Meets Ancient Texts

Published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, the new study combines archaeology, mineralogy, and geochemistry to investigate whether Terra di Nocera and creta umbrica are, in fact, the same material separated by centuries of changing names and uses.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The researchers analyzed samples of Terra di Nocera taken directly from its geological source—the Scaglia Cinerea Formation, a marly limestone formation characteristic of the Umbrian Apennines. Using X-ray diffraction and chemical analyses, they identified a mineral composition dominated by calcite, illite, and smectites—clay minerals well known for their absorbent and cleansing properties.

These findings align strikingly well with Pliny’s descriptions. In Roman textile processing, absorbency was everything. Wool garments were treated with clays to remove oils and restore brightness after sulfur fumigation. The mineral profile of Terra di Nocera makes it exceptionally suited to precisely those tasks.

Clues from Ancient Graves

The investigation did not stop at geology. Archaeological evidence provided an even deeper historical dimension.

Excavations at the Umbrian necropolises of Colfiorito and Serravalle di Chienti, dating from the 9th to the 3rd century BC, revealed unfired clay “loaves” placed deliberately in elite burials. These raw clay masses—sometimes weighing several kilograms—were positioned near the feet or head of the deceased, and occasionally inside ritual vessels.

Chemical analyses of several of these clay loaves showed a strong compositional similarity to Terra di Nocera and the Scaglia Cinerea Formation. This suggests a shared origin and indicates that the clay held symbolic as well as practical significance long before Roman times.

Researchers propose that these clay loaves may have served a dual role: practical, linked to textile production and domestic life, and symbolic, associated with healing, purification, or ritual protection in death.

From Funerary Rituals to Fuller’s Workshops

By the Roman Imperial period, the role of Umbrian clay appears to have shifted from ritual object to industrial material. Pliny describes how different clays were used at specific stages of cloth production—washing, fumigation, and finishing—highlighting a sophisticated understanding of material properties.

Creta umbrica, in particular, was valued for restoring garments rather than whitening them, suggesting a gentler but highly effective action. The fact that it was sold by volume, not weight, further implies that it did not expand dramatically when wet—a detail consistent with the mineral behavior identified in Terra di Nocera.

Reinvented in the Modern World

By the 16th century, references to Terra di Nocera re-emerge in medical texts, poetry, and local traditions. Physicians debated whether it resembled famous medicinal clays from Lemnos or Samos, while others dismissed classification altogether in favor of its perceived benefits.

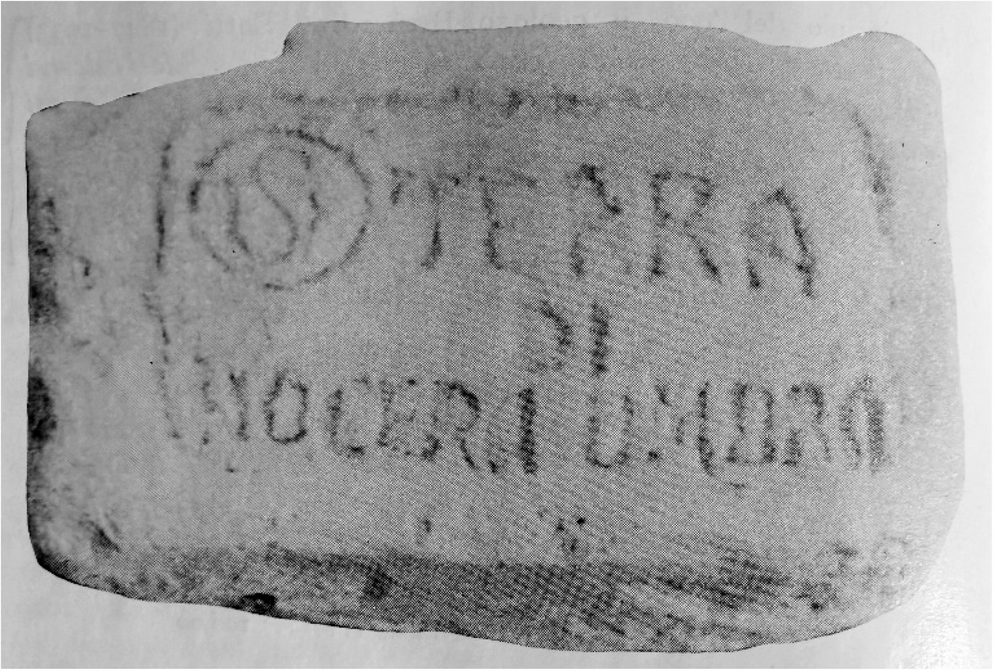

In the 20th century, Terra di Nocera was even marketed as a soap substitute, stamped into bars and sold commercially. Modern analyses, however, confirm that its cleansing power is mechanical rather than chemical—a natural degreaser rather than a true soap.

Despite bold contemporary marketing claims, the study is careful to note that no clinical evidence currently supports many of the health benefits attributed to Terra di Nocera today. Its true value lies not in miracle cures, but in its long, well-documented functional history.

A Material That Endures

While the identification of Terra di Nocera with Pliny’s creta umbrica cannot be proven beyond doubt, the convergence of historical texts, archaeological finds, and modern scientific data makes the connection compelling.

More importantly, the study highlights how natural materials can persist across millennia, adapting to new cultural contexts while retaining their essential properties. From ancient funerary rites to Roman workshops and modern wellness products, Umbrian clay tells a story not of superstition, but of continuity.

In an age obsessed with innovation, Terra di Nocera reminds us that some of humanity’s most enduring technologies were perfected long ago—quietly, in the earth beneath our feet.

Gliozzo, E., Fantozzi, P.L., Frapiccini, N. et al. Pliny’s Creta umbrica reconsidered: connections with Terra di Nocera and clay loaves from Umbrian necropoleis. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 18, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-025-02379-0

Cover Image Credit: A mid-20th-century stamped soap bar labelled “Terra di Nocera Umbra” from Sigismondi (1979). Gliozzo, E., Fantozzi, P. L., Frapiccini, N., et al. (2026)