A major archaeological discovery in Germany is reshaping long-held assumptions about one of Europe’s most iconic imperial monuments. The tomb of Emperor Otto I, known as Otto the Great, located in Magdeburg Cathedral, has revealed a surprising secret: the marble slab covering his sarcophagus does not originate from Italy or Greece, as scholars believed for decades, but from the Marmara Island in modern-day Turkey.

This groundbreaking finding emerged during an extensive conservation and restoration project launched in January 2025 by the Cultural Foundation of Saxony-Anhalt and the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology (LDA) Saxony-Anhalt. The project aims to preserve one of the most important monuments of medieval Europe while applying state-of-the-art scientific methods to uncover new historical insights.

Otto the Great and the Heart of Medieval Europe

Emperor Otto I (912–973) is regarded as one of the most influential rulers in European history. As the successor to Charlemagne’s imperial vision, he revived the Roman Empire in Western and Central Europe, laying the foundations for what would later become the Holy Roman Empire. His reign reshaped political, religious, and cultural structures across the continent.

Otto’s deep connection to Magdeburg played a crucial role in the city’s rise. In 968, he elevated Magdeburg to the status of an archbishopric, triggering economic prosperity and cultural growth along the Elbe River. Following his death in 973, the emperor was buried in Magdeburg Cathedral, where his tomb remains a central landmark to this day.

A Conservation Project Unlocks Hidden History

While the tomb has been revered for centuries, recent monitoring revealed alarming structural damage, prompting urgent conservation measures. During the restoration, experts carefully removed the marble lid of the stone sarcophagus in March 2025, allowing researchers to examine its underside for the first time.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

It was already known that the sarcophagus itself was carved from limestone, while the lid was made of distinctive white marble with dark grey banding. Historians long suspected that the slab was reused from antiquity—but its true origin remained uncertain.

The representative cover slab removed from the stone box, which was examined by specialists from Vienna and Bochum for the provenance of ancient marble. Credit: State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology, Saxony-Anhalt, Andrea Hörentrup

Scientific Analysis Reveals a Surprising Origin

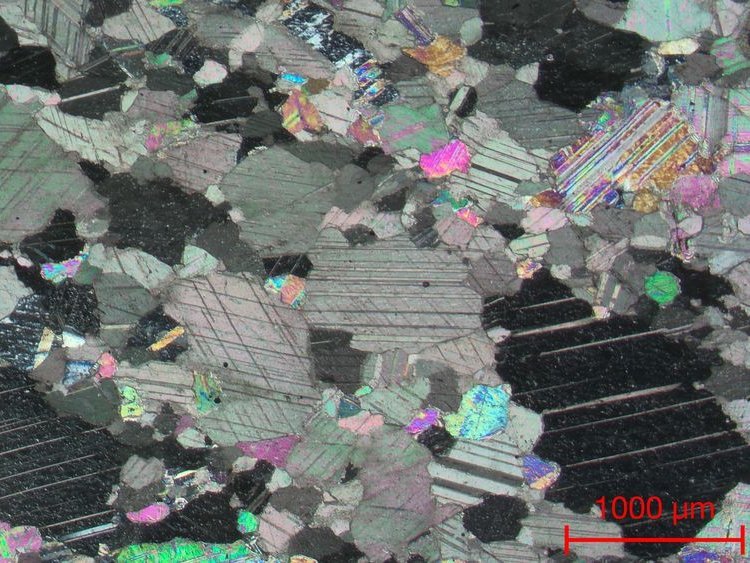

To solve the mystery, leading marble specialists from Vienna and Bochum conducted an in-depth material analysis. Small core samples were extracted from both the white and dark layers of the marble. These samples underwent microscopic petrographic examination, chemical analysis, and isotopic testing.

The results were then compared with a vast reference database of approximately 7,500 marble samples from ancient quarries across the Mediterranean, Northern Italy, and the Alpine region.

The conclusion was definitive: the marble originates from the Prokonnesos quarries on Marmara Island, located in the Sea of Marmara, Türkiye. This marble—known as Proconnesian or Marmara marble—has been quarried since the 7th century BC and was widely used in Late Antiquity.

From Constantinople to Ravenna – and Finally to Magdeburg

Proconnesian marble is characterized by its bright white color and sharply defined grey bands. Interestingly, the banding pattern on Otto’s tomb slab is tightly folded and angled diagonally—an artistic cutting style that became fashionable only in Late Antiquity.

Comparable marble elements can be found in some of the most significant monuments of the ancient and medieval world, including Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice, and numerous churches in Ravenna, Italy.

Based on these parallels, researchers believe the marble slab originally formed part of an architectural structure in Ravenna, one of the most important cities of the late Roman Empire. It was likely used as wall cladding or flooring before being removed and transported north.

Spolia, Power, and Imperial Prestige

During the Middle Ages, the reuse of ancient building materials—known as spolia—was both common and symbolic. Transporting raw marble directly from Anatolia to Germany during Otto’s reign would have been logistically and politically unrealistic. Instead, valuable stone elements were often taken from Roman and late antique buildings in Italy and repurposed for imperial projects.

Otto the Great spent nearly ten years in Northern Italy, making it highly plausible that the marble slab was acquired there and brought to Magdeburg as a prestigious trophy of imperial authority. Even Charlemagne is known to have imported spolia from Rome and Ravenna to legitimize his rule through association with Roman legacy.

Microscopic image of the marble sample from the white area of the tombstone under a polarization microscope, showing the characteristic, uneven-grained ‘mortar’ texture of Proconnesian marble. Credit: Institute of Archaeological Sciences, Ruhr University Bochum, Vilma Ruppiene

A Monument of European Heritage

The discovery highlights the deep interconnectedness of Europe, the Mediterranean, and Anatolia long before the modern era. A single marble slab now tells a story spanning centuries, empires, and continents—from ancient quarries in Turkey to imperial Italy and medieval Germany.

As conservation work continues into 2026, Otto the Great’s remains will remain in Magdeburg, while researchers promise to keep the public informed through exhibitions and digital displays inside the cathedral.

This remarkable finding not only enriches our understanding of Otto the Great’s tomb but also underscores the enduring value of scientific archaeology in preserving and reinterpreting Europe’s shared cultural heritage.

Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt

Cover Image Credit: Tomb of Otto I in Magdeburg Cathedral – Public Domain