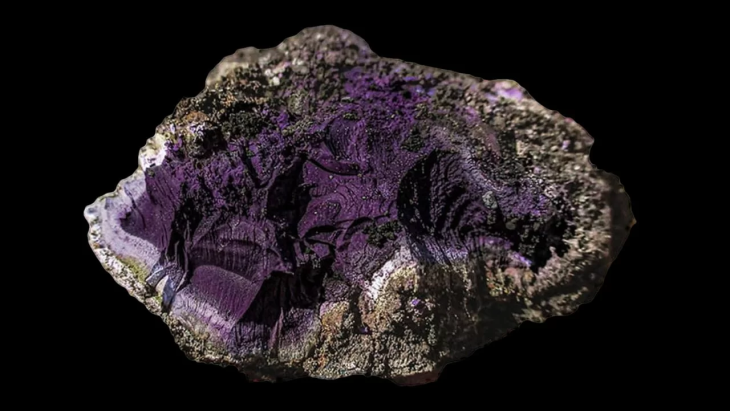

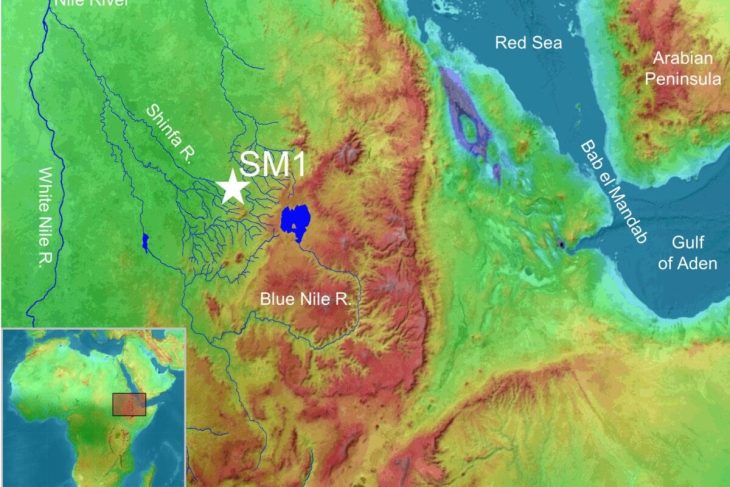

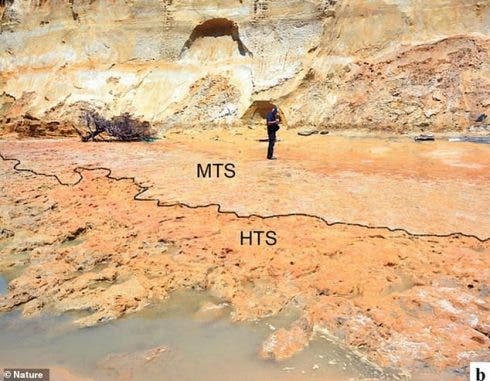

A stroll along the beach of Matalascanas (Huelva) in June of last year unearthed a spectacular scenario that occurred in this area more than 100,000 years ago. Winter storms and high tides exposed a 6,000-square-meter field.

The site revealed a massive amount of well-preserved fossil footprints (ichnites) of large vertebrates such as aurochs, deer, wild boar, elephants, canids, and waterfowl, among others (geese, waders, etc.). However, amid the many animal tracks, this remarkable document uncovered another significant discovery: the presence of human footprints.

The role of human ichnites is critical to understanding facets of our ancestors’ biology and behavior as there are no records of bones or teeth.

The footprints provide a glimpse into specific events of their lives that have been preserved in time. In this way, footprints provide crucial information about the number of people who made them, as well as their biological features (height, age, body mass, sex), and even biomechanics (posture, gait, speed).

However, as compared to other archaeological or palaeoanthropological sites, the number of sites with this type of footprint remains relatively scarce worldwide, especially those associated with Neanderthal hominids.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

This is the case in the Iberian Peninsula, where Neanderthal bones and industrial (lithic industry) remains have been discovered in many locations. For instance, the Arrábida coast in Portugal, Málaga’s Bajondillo and Abrigo 3 caves, and Gibraltar’s Vanguard and Gorham caves.Just one badly preserved footprint has been found in Gibraltar’s Catalán Bay, but its attribution is dubious since its age (28 000 years) corresponds to a period when Neanderthals were extinct in Europe.

The Matalascaas footprints are the first undeniable record of Neanderthal hominid footprints discovered on the Iberian Peninsula, and they are the world’s earliest, dating from the Upper Pleistocene (from 129 000 to 11 700 years ago). The footprints are more than 106 000 years old.

The analysis of the shape and proportions (morphometry) of the full footprints has enabled scientists to determine not only whether they match the characteristics of these ancient hominids’ feet, but also the group’s biological and social characteristics.

Thus, the body height corresponding to 31 of the footprints may be estimated, with 7 identified with infants, 15 with youth, and 9 with adults. The two smallest footprints age of 6 years, while 11 footprints fall anywhere between children and adolescents.

In addition, 5 footprints lead to heights between 140 and 155 cm and are correlated with teenagers. Adult Neanderthal females or small males may, however, have made them.

The footprints are spread around an NW-SE swath on the edge of what was once a flooded field, most likely seasonal, and only reaching into the water. Since the majority of them are perpendicular to the same course, the more plausible explanations would be tracking and stalking animals in the sea.

The idea that it was a staging area or part of a migratory path cannot be ruled out, but the possibility of a group bearing any sort of load is impossible to detect based on the morphology of the tracks alone.

Experiment results reveal that the overall length of the footprints varies just slightly (less than one cm on average) as people walk with or without a load.

The findings are published in Scientific Reports.