Two small gold objects discovered in Mycenaean tombs on the Greek island of Cephalonia are reshaping what archaeologists know about cultural connections at the end of the Bronze Age. A new study published in the European Journal of Archaeology reveals that the solar symbols decorating these ornaments originated not in the Aegean, but in Northern and Central Europe—offering striking evidence of long-distance interaction, hybrid art, and early globalization in the 12th–11th centuries BC.

A Remarkable Discovery in Mycenaean Cemeteries

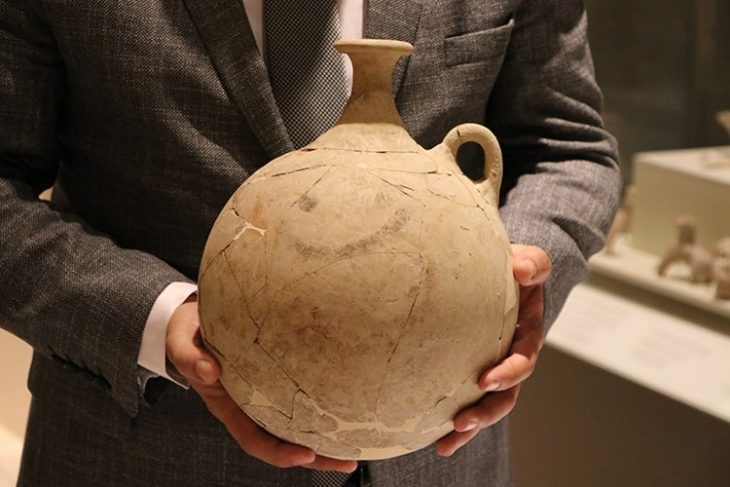

The artifacts were unearthed in two separate Late Bronze Age cemeteries in the Livatho region of southwest Cephalonia. Both objects are crafted from hammered gold and date to the post-palatial Mycenaean period, a time marked by political fragmentation but expanding maritime mobility.

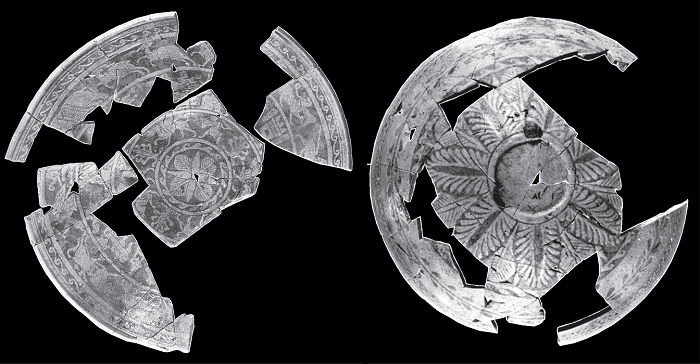

The first object, found at Mazarakata, is a fragment of a circular gold disk once measuring around 12 centimeters in diameter. It is decorated with concentric circles in relief—a striking but unfamiliar motif in Mycenaean visual culture.

The second object, discovered at Lakkithra, is a complete elongated gold ornament about 9.7 centimeters long. It features a four-spoked wheel—a cross enclosed within a circle—flanked by two bands ending in symmetrical volutes. This piece was recovered from a collective “cave-dormitory” tomb alongside weapons, pottery, and what may have been a wooden shield, strongly suggesting the burial of a warrior.

Solar Symbols from the European North

What makes these objects exceptional is not their material value, but their iconography. According to the study, neither the concentric circles nor the four-spoked solar wheel are typical of Mycenaean art. Instead, these motifs closely resemble solar symbols widely used in Bronze Age Northern and Central Europe, where they were deeply tied to cosmology, religious belief, and the sun’s daily journey across the sky.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Comparable gold disks have been found in Italy, particularly at Gualdo Tadino in Umbria and Rocavecchia in Apulia. These Italian examples are themselves understood as adaptations of Central European solar imagery, creating a cultural chain that stretches from northern Europe to the eastern Mediterranean.

Not Simple Imports, but Cultural Hybrids

Rather than viewing the Cephalonia objects as straightforward imports, the researchers argue for a more complex process of transcultural exchange.

The Mazarakata disk is the closest match to the Italian examples and may indeed be a foreign-made object that entered the Mycenaean world through exchange or travel. Its probable use as a funerary garment ornament aligns with Aegean burial practices, although the use of gold in this context was rare and prestigious.

The Lakkithra ornament, however, tells a more intricate story. While the central solar wheel clearly reflects European symbolism, other features are distinctly Mycenaean. The volutes may reinterpret familiar Aegean spiral or lily motifs, while the zigzag infill parallels decorative patterns found on local pottery. Even the manufacturing technique—folded edges used for attachment—matches Mycenaean goldworking traditions.

This object represents what scholars describe as “material entanglement” or “creative translation”: a hybrid artifact in which foreign ideas are actively reworked to fit local artistic language and belief systems.

Function, Symbolism, and the Afterlife

The precise function of the Lakkithra ornament remains debated. Based on its shape, researchers suggest it may have covered the handle of a bronze mirror or possibly the hilt of a small dagger. The mirror interpretation is particularly compelling.

Mirrors were elite objects in the Late Bronze Age Aegean and are overwhelmingly found in funerary contexts. Across cultures, mirrors often carry symbolic links to the sun due to their reflective surfaces. This association reinforces the meaning of the solar imagery and suggests the object may have played a role in beliefs about death, rebirth, or the soul’s journey.

In European Bronze Age iconography, solar symbols are frequently linked with boats and chariots—vehicles of cosmic travel. Similar ideas existed in the Aegean, where boats, birds, and water were long associated with the divine and the afterlife.

Cephalonia at the Crossroads of the Bronze Age World

The study places Cephalonia within a dense network of maritime routes connecting the Aegean, the Adriatic, and Italy, and ultimately Central Europe. After the collapse of the Mycenaean palace system, these routes became less regulated, allowing local elites greater freedom to travel, trade, and form alliances.

Archaeological evidence supports this picture. Baltic amber beads, likely arriving via northern Italy, and glass beads linked to the Po Valley site of Frattesina have also been found in Cephalonia’s cemeteries. Together, these finds suggest that island elites—possibly warriors—were active participants in long-distance exchange networks.

A Bronze Age World More Connected Than We Imagined

As author Christina Souyoudzoglou-Haywood emphasizes, these gold ornaments are powerful indicators of both early globalization and cultural adaptability. Rather than passively absorbing foreign ideas, Mycenaean communities selectively adopted and reshaped them within their own symbolic frameworks.

Ultimately, these two small objects provide outsized insight into a dynamic, interconnected Bronze Age Mediterranean—one in which ideas, symbols, and beliefs traveled as far and as meaningfully as goods themselves.

Souyoudzoglou-Haywood C. The Aegean Meets Europe: Two Ornaments with Solar Motifs from Mycenaean Kefalonia (Greece). European Journal of Archaeology. Published online 2026:1-19. doi:10.1017/eaa.2025.10031

Cover Image Credit: Gold ornament from Lakkithra. Greek Ministry of Culture, Ephorate of Antiquities of Kephallenia and Ithaki.