Archaeologists working in Siberia have identified a series of early medieval child burials containing jewelry, ornate belts, and high-status dress elements, shedding new light on how social rank and identity were assigned from a very young age in ancient societies.

The discoveries come from burial sites associated with the Upper Ob cultural sphere, dated between the 5th and 8th centuries AD, and include elite child graves furnished with objects typically reserved for powerful adults. According to researchers, these finds challenge modern assumptions about childhood and suggest that social status in early medieval Siberia was inherited—and symbolically displayed—almost from birth.

The study was led by Andrey Pavlovich Borodovsky, a professor and archaeologist at Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University, who examined child burials spanning multiple historical periods across Western Siberia.

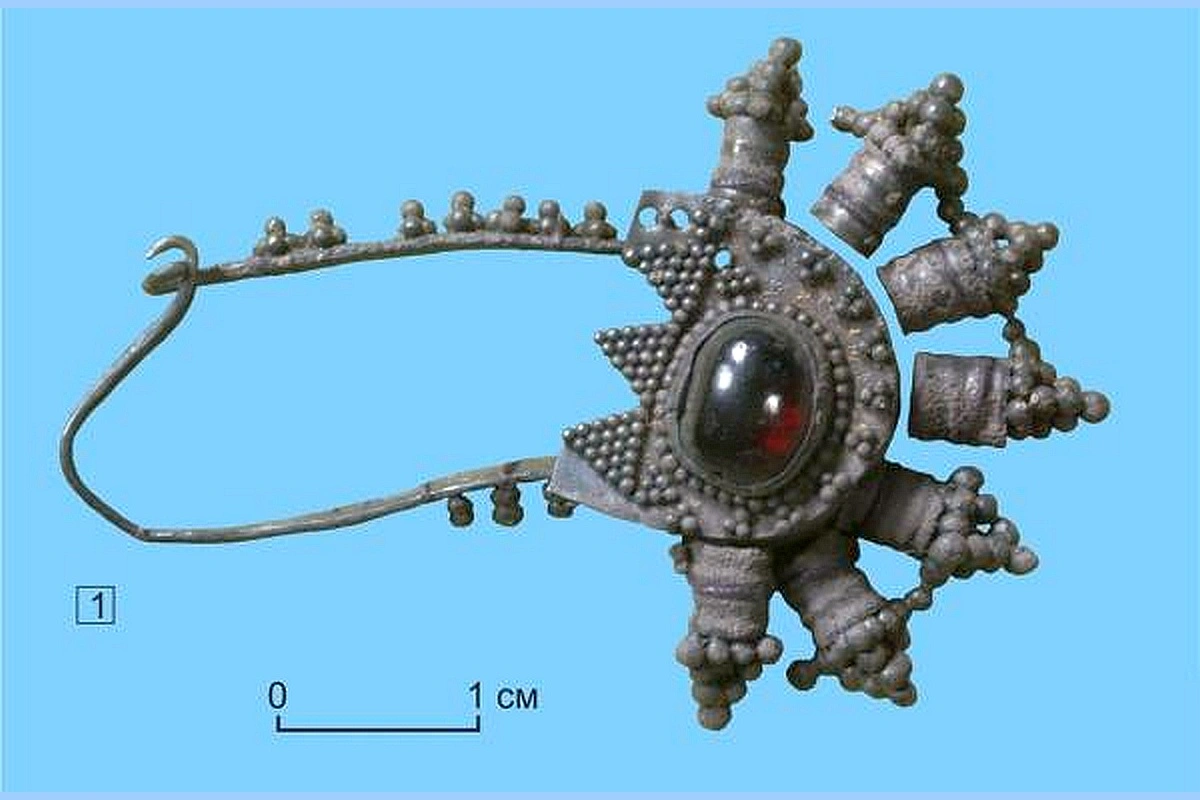

Jewelry, Belts, and a Byzantine-Style Fibula

Excavations at sites such as Ivanovka-6, Umna-2, Umna-3, and Yurt-Akbalyk-8 revealed children buried with composite belts, metal ornaments, and finely crafted jewelry. One of the most striking finds came from Ivanovka-6: a silver fibula pendant set with a garnet, stylistically comparable to objects known from the Byzantine world.

The presence of such an object far from the Mediterranean does not necessarily indicate direct contact with Byzantium, but it strongly suggests that Upper Ob elites participated in long-distance symbolic and stylistic exchange networks stretching across Eurasia. These imported or imitated forms were likely used to signal prestige rather than function.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Borodovsky argues that the richness of these graves should not be interpreted simply as expressions of parental grief or affection. Instead, the burial inventories reflect structured social processes and the public affirmation of elite identity.

Children as Bearers of Status

“What we see in these elite child burials is not sentimental excess,” Borodovsky explains, “but a deliberate and highly mythologized ritual language.”

According to the researcher, early medieval societies in Southern Siberia and Central Asia developed powerful narratives centered on the figure of the ‘royal’ or heroic youth. These myths emphasized predestined leadership, sacred lineage, and inherited authority—concepts that appear to be mirrored in burial practice.

The uniqueness and surplus of grave goods in elite child burials support this interpretation. Children were not viewed as incomplete social beings, but as full carriers of status, already embedded within their community’s hierarchy.

Ethnographic Parallels and Cultural Continuity

Ethnographic evidence supports this long-standing tradition. Among the Tuvan people, for example, boys were historically dressed at a very young age in garments bearing the same markers of rank as those worn by adult men. Central to this outfit was the belt, often crafted by the father, symbolically initiating the child into the adult social world.

Such practices suggest deep cultural continuity and help archaeologists interpret the symbolic meaning of belts and ornaments found in ancient child graves.

From Jewelry to Uniforms: A Shift in Symbols

This emphasis on visible status did not disappear with time—it evolved. When Western Siberia became part of the Russian state, new symbols of authority replaced older ones. The most powerful of these was the official uniform.

A compelling later example comes from Umrevinsky Ostrog, where archaeologists uncovered the burial of a boy aged approximately six to twelve years, dating to the late 18th or early 19th century. The child was interred wearing a uniform with silver embroidery, closely resembling attire used by Russian mining and industrial administration.

This burial demonstrates how state symbols were absorbed into local ritual practice, continuing the tradition of expressing status through dress—even in childhood.

Rethinking the History of Childhood

The Siberian discoveries also contribute to a broader reassessment of childhood as a historical concept. Borodovsky notes that the modern idea of childhood as a protected, separate life stage is remarkably recent, emerging only around the last 120 years.

For most of history, children were integrated into social systems from infancy and assigned clearly defined roles. The graves of elite children in Siberia preserve this worldview in material form.

“These burials allow us to trace how societies understood childhood,” Borodovsky concludes. “Not as a time of waiting—but as an active social condition.”

Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University (NSPU)

Cover Image Credit: Silver fibula pendant with a garnet cabochon and granulation, discovered at the Ivanovka-6 site. Novosibirsk State Pedagogical University (NSPU)