New isotopic research reveals that seabird droppings fueled the rise of the Chincha Kingdom on Peru’s arid Pacific coast

When we imagine the wealth of ancient South American civilizations, we tend to picture gold masks and silver ornaments. But for the Chincha Kingdom, which flourished on Peru’s southern coast between 1000 and 1400 CE, true power came from something far less glamorous: seabird guano.

A new multidisciplinary study published in PLOS One demonstrates that marine bird fertilizer played a decisive role in transforming one of the driest regions on Earth into a productive agricultural landscape. Through chemical analyses of ancient maize cobs, researchers now present some of the strongest evidence to date that seabird guano fueled the economic and political expansion of this pre-Inca society.

Chemical Fingerprints in Ancient Maize

The Chincha Valley lies within Peru’s coastal desert—a region where agriculture is only possible through irrigation. Yet irrigation alone comes at a cost. Sandy soils quickly lose nutrients, and without replenishment, crops fail.

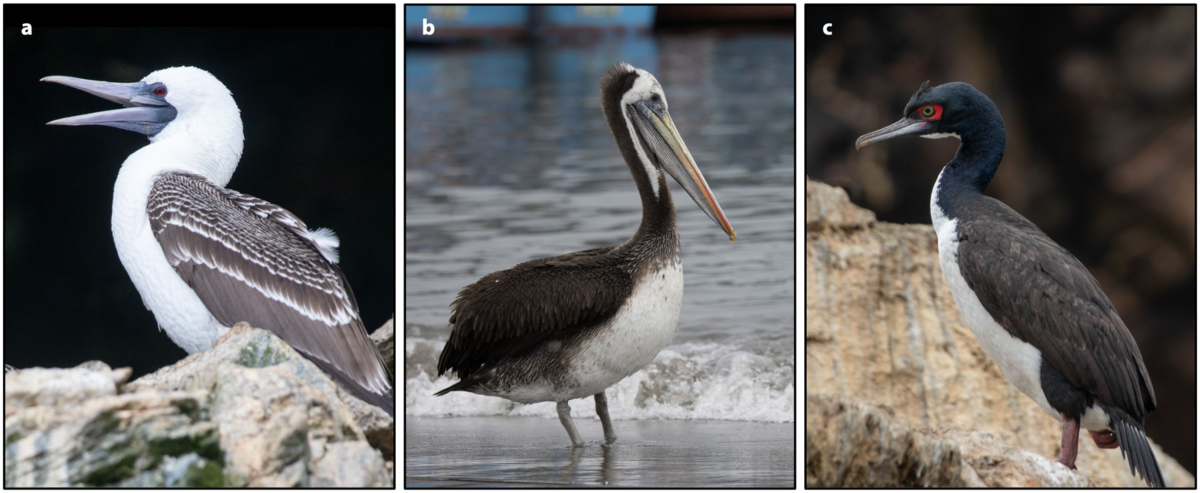

The solution lay just 25 kilometers offshore on the Chincha Islands. These rocky outcrops were home to vast colonies of guano-producing seabirds such as the guanay cormorant, the Peruvian booby, and the Peruvian pelican. Their nitrogen-rich droppings accumulated in thick deposits that would later become globally famous in the 19th-century fertilizer trade.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

But this “white gold” was already being exploited centuries earlier.

Researchers analyzed 35 maize cobs recovered from Chincha Valley burials, spanning periods from the late Formative era (ca. 200 BCE) to the Colonial period. Using stable isotope analysis—specifically nitrogen (δ¹⁵N), carbon (δ¹³C), and sulfur (δ³⁴S)—the team searched for biochemical signatures of fertilization.

The results were striking. Some maize samples reached nitrogen isotope values as high as +27.4‰. For comparison, unfertilized crops typically show values below +10‰. Experimental and archaeological research demonstrates that only seabird guano reliably produces nitrogen values exceeding +20‰ in plants.

In other words, the chemical evidence points clearly toward intensive guano fertilization by at least 1250 CE.

Fertilizer as Political Power

Why does this matter?

Because agricultural surplus is the foundation of state formation.

The Chincha Kingdom was not a loose farming community. At its peak, it was a centralized polity with an estimated 30,000 tribute-paying households and possibly over 100,000 inhabitants. Specialized farmers, fisherfolk, and merchants formed an interconnected economic system. Maritime traders sailed along the Pacific coast, reaching as far as present-day Ecuador.

For decades, scholars assumed that long-distance trade in luxury goods—particularly Spondylus shells—underpinned Chincha wealth. The new study shifts that narrative. Instead, guano fertilization likely enabled dramatic increases in maize production, generating surplus that supported population growth, trade expansion, and regional influence.

“Seabird guano may seem trivial,” the authors write, “but it likely contributed significantly to the sociopolitical and economic transformation of the Peruvian Andes”.

In the Andes, fertilizer was power.

A Culture Rooted in Ecological Knowledge

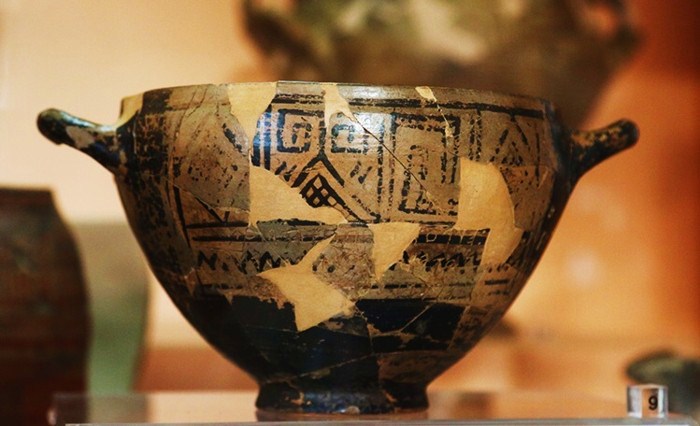

Archaeology reinforces the isotopic findings. Chincha textiles, ceramics, wooden artifacts, and architectural friezes frequently depict seabirds, fish, and maize. These images are not decorative coincidences. They reflect a cultural understanding of the ecological chain linking marine life to agricultural fertility.

Fisherfolk harvested guano from offshore islands using balsa rafts. Farmers applied it to maize fields. Merchants distributed surplus crops across regional trade networks.

This integrated marine–terrestrial economy was deeply embedded in Chincha society.

Diplomacy with the Inca Empire

By the 15th century, the expanding Inca Empire incorporated the Chincha Kingdom. Unlike many conquests marked by violence, Chincha appears to have negotiated a strategic alliance.

Why?

The Inca state depended heavily on maize, particularly for producing chicha, a fermented ceremonial drink. Yet highland environments limited maize cultivation. Access to guano—an unparalleled fertilizer—would have been strategically invaluable.

The study suggests that Chincha control over guano resources strengthened its negotiating position. Colonial accounts even note that the Chincha lord was the only dignitary besides Inca ruler Atahualpa permitted to be carried on a litter—a powerful symbol of status.

Guano may have been central to that prestige.

Rethinking Ancient Diets

The research also carries methodological implications. Elevated nitrogen values caused byguano fertilization can mimic marine-based diets in human skeletal remains. Without careful analysis, archaeologists might mistakenly conclude that ancient populations consumed large quantities of seafood when, in fact, they were eating maize grown with marine fertilizer.

Sulfur isotope analysis (δ³⁴S) was tested as an additional tool to distinguish between marine diets and marine-fertilized crops. While sulfur results proved more complex and variable, the combined isotopic approach offers new pathways for refining paleodietary reconstructions.

An Indigenous Land-Management Strategy

Guano fertilization was not a marginal practice. It was a sophisticated land-management system rooted in local ecological expertise.

Historical records describe strict regulations protecting guano islands during Inca rule. Killing seabirds during breeding season could be punishable by death. Such measures reflect a clear recognition of guano’s economic and agricultural importance.

The Chincha case demonstrates that marine fertilizers were already transforming agricultural systems centuries before industrialized fertilizer production.

Ecological Wisdom in the Desert

The Peruvian coastal desert remains one of the most arid environments on Earth. Sustaining large populations there required deep environmental knowledge.

The Chincha did not merely possess access to a resource. They mastered a complex ecological network linking ocean currents, seabird colonies, soil chemistry, irrigation systems, and maize production.

Their power was not forged in gold.

It was built on nitrogen.

And as this new study shows, ecological wisdom helped lay the foundation for one of the most influential pre-Inca societies on the Pacific coast of South America.

Bongers JL, Milton EBP, Osborn J, Drucker DG, Robinson JR, et al. (2026) Seabirds shaped the expansion of pre-Inca society in Peru. PLOS ONE 21(2): e0341263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0341263

Cover Image Credit: Seabirds shaped the expansion of pre-Inca society in Peru. Bongers JL (2026), PLOS ONE