Despite the widely acknowledged monumentality and durability of ancient Egyptian sculpture, carved reliefs, and paintings the makers of these works remain mostly unknown.

For a long time, academics considered tomb and temple decorations as sources of knowledge about ancient Egyptian religious beliefs rather than works of art in their own right. Little is known about individual Egyptian artists and their methods. Textual evidence suggests the presence of sculptors and painters, but rarely provides specifics about their work or who they were.

In a new approach, archaeologists have revealed that Egyptian sculptors worked in teams rather than solo artisans.

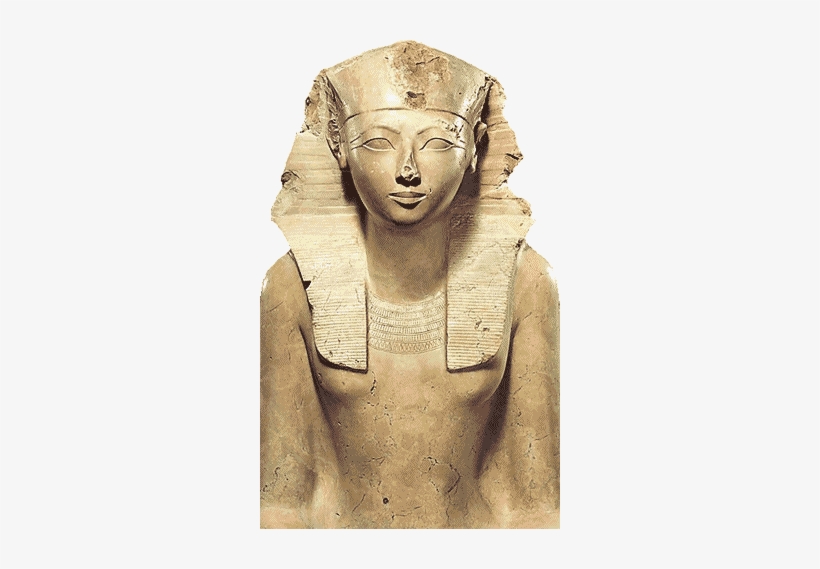

Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska and colleagues from the University of Warsaw researched the temple of Hatshepsut, one of Egypt’s few female pharaohs who reigned from 1478 to 1458 B.C.E.

To better understand the work of decorating ancient temples, Anastasiia Stupko-Lubczynska, an archaeologist at the University of Warsaw, and his colleagues studied the Temple of Hatshepsut.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Maat-Ka-Re Hatshepsut (XVIIIth Dynasty, circa 1479-1457 BC) was the daughter of Aa-kheper-ka-Re Thutmosis I, and the wife of Aa-kheper-en-Re Thutmosis II. She was the third woman in Egyptian history to take up the Pharaoh’s throne.

Queen Hatshepsut was a great builder sovereign, who showed evidence of outstanding originality. The temple of Deir el-Bahari is the most spectacular example of it.

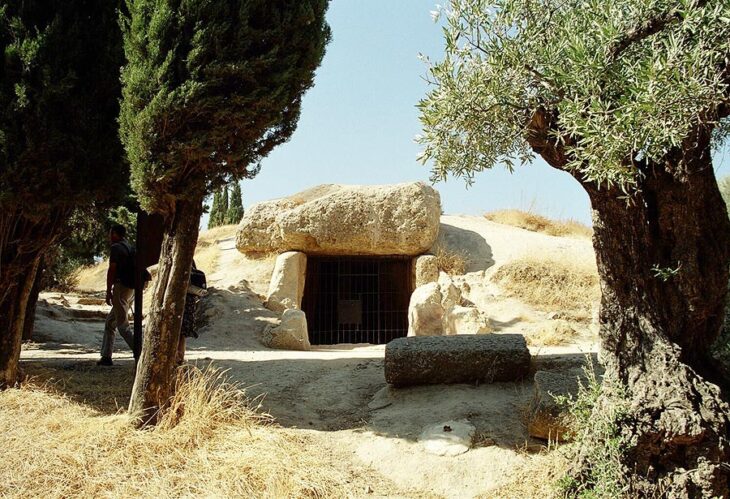

Hatshepsut temple, which stretches 273 meters by 105 meters, was built almost 3500 years ago at Deir el-Bahari, near modern-day Luxor.

Stupko-Lubczynska was there as part of the University of Warsaw’s Polish-Egyptian expedition’s painstaking—and ongoing—effort to clean and restore the temple’s damaged walls.

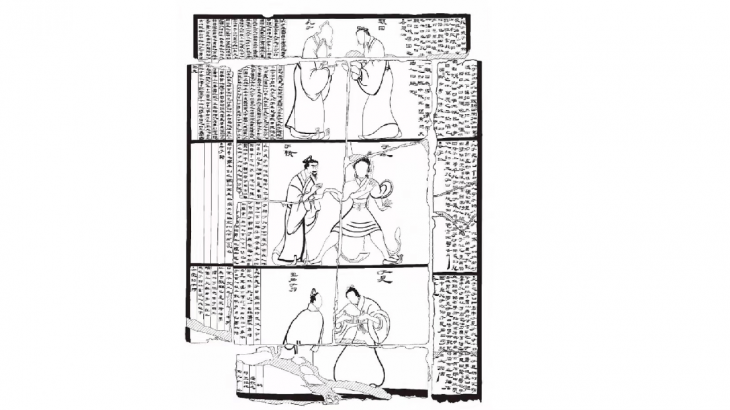

Stupko-Lubczynska and a team of draftspeople spent hundreds of hours between 2006 and 2013 documenting the chapel walls by hand, copying the carvings on sheets of plastic film at a one-to-one scale.

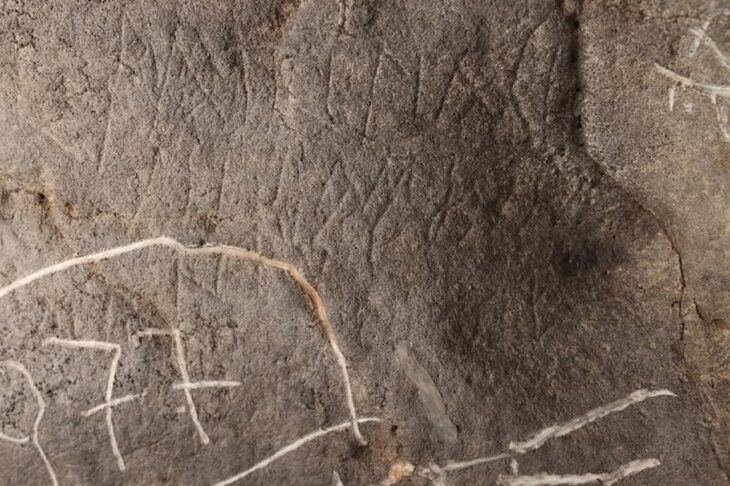

During the procedure, the archaeologist discovered minute features in the chapel’s fragile limestone, such as awkward chisel strokes and subsequent adjustments.

“Because we have so many figures with repetitive details, we can compare the details and workmanship,” Stupko-Lubczynska says. “If you look at enough of them, it’s easy to see when someone was doing it properly.”

Some figures, she and her coworkers saw, were noticeably worse—legs and torsos with sloppily chiseled edges, or many chisels blows to sculpt wig curls that only required two or three precise strokes elsewhere.

Stupko-Lubczynska said today in Antiquity that the study showed the painting was a collaborative effort done in stages by different painters.

“Maybe the master artisans came in at the end to finish the figure.” With no natural light in the cavernous, windowless hall, there must have also been assistants holding oil lamps crowding onto the scaffolds.” she says.

As a result of the research, the process of creating Ancient Egyptian reliefs was well understood.

The examination of the procedures utilized and the sequencing of the acts necessary to manufacture an item is known as the chaîne opératoire in archaeology (operational sequence). The chaîne opératoire approach was applied to the wall reliefs in the Chapel of Hatshepsut, the largest room in the temple built for the eponymous female pharaoh.