A groundbreaking study from Georgia’s Kvemo Bolnisi site reveals that Bronze Age metallurgists were experimenting with iron oxides long before iron smelting became a dominant technology.

Archaeologists have long debated how and where humanity first mastered the technology of producing iron, the metal that would come to define entire civilizations. A new scientific study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science (2025), sheds fresh light on this mystery by re-examining one of the Caucasus region’s most intriguing archaeological sites: Kvemo Bolnisi in southern Georgia.

Originally excavated in the late 1950s, Kvemo Bolnisi was once thought to be among the earliest iron smelting workshops. However, new chemical and microscopic analyses of metallurgical debris tell a different story. Researchers Nathaniel L. Erb-Satullo and Bobbi W. Klymchuk from Cranfield University demonstrate that the site was in fact a copper smelting workshop, active in the late second millennium BC—yet with a twist that has profound implications for the history of metallurgy.

From Bronze to Iron: A Technological Turning Point

The transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, around 1200 BC, remains one of the most pivotal shifts in human history. Bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, had dominated weaponry, tools, and trade for centuries. Iron, however, was tougher, more abundant, and ultimately cheaper. The spread of iron technology restructured economies, military power, and trade networks across the ancient Near East and Mediterranean.

Yet one puzzle has persisted: how exactly did ancient metallurgists discover that iron-bearing minerals could be intentionally reduced to produce workable iron? Did the breakthrough occur by accident, or as part of deliberate experimentation?

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The evidence from Kvemo Bolnisi offers one of the clearest answers yet.

Hematite as a Deliberate Flux

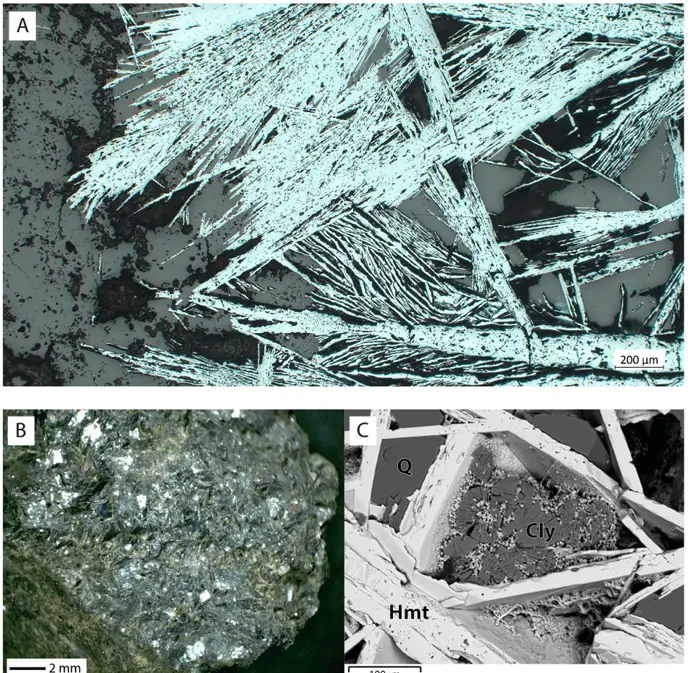

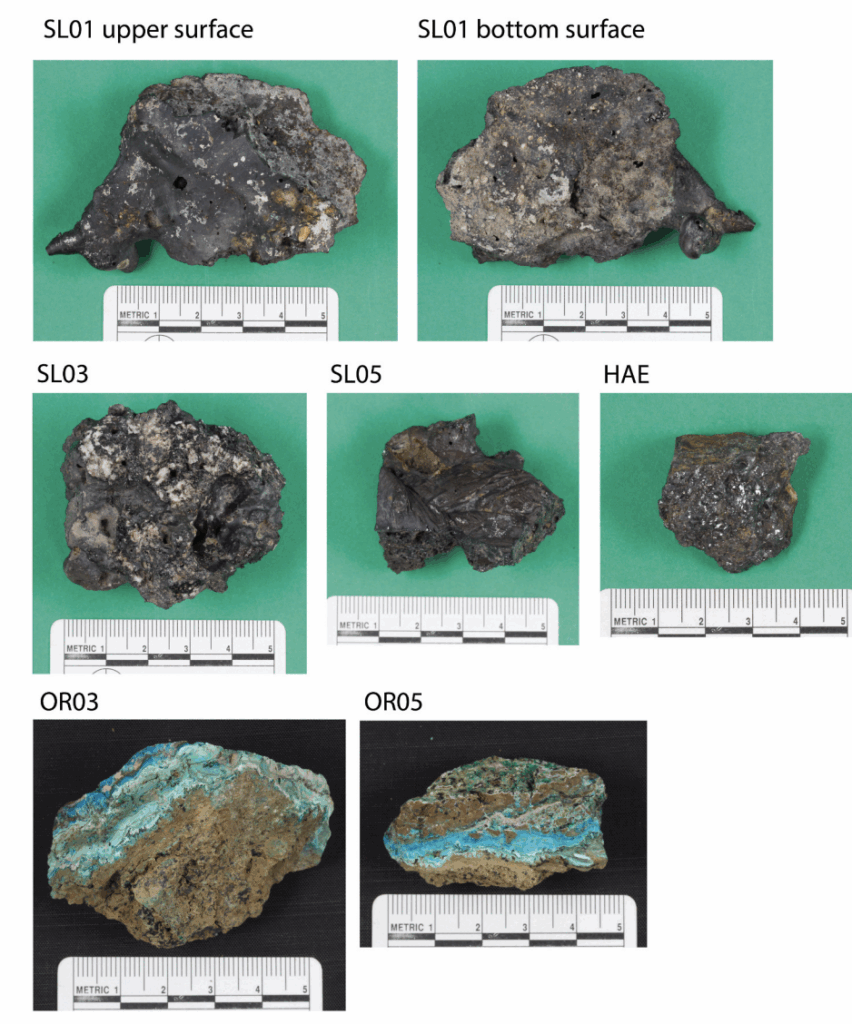

The research team analyzed slags, ores, and minerals recovered from the site using scanning electron microscopy (SEM-EDS) and optical microscopy. They found unequivocal proof that copper—not iron—was the primary product. But the slags also revealed something extraordinary: chunks of hematite (iron oxide) had been deliberately added into the furnace charge.

Rather than smelting iron, Bronze Age metallurgists were using hematite as a flux—a material that lowers the melting point of silica-rich ores, creating a more fluid slag. This made it easier to separate copper metal from impurities, increasing yields.

Crucially, this demonstrates that ancient smelters recognized iron oxides as a distinct, manipulable material. They were not merely encountering iron by accident in their ores but were stockpiling and deliberately applying it as part of their metallurgical process.

This intentionality marks a cognitive leap: an early understanding of iron’s properties that may have laid the groundwork for the eventual invention of iron smelting itself.

A Caucasian Laboratory of Innovation

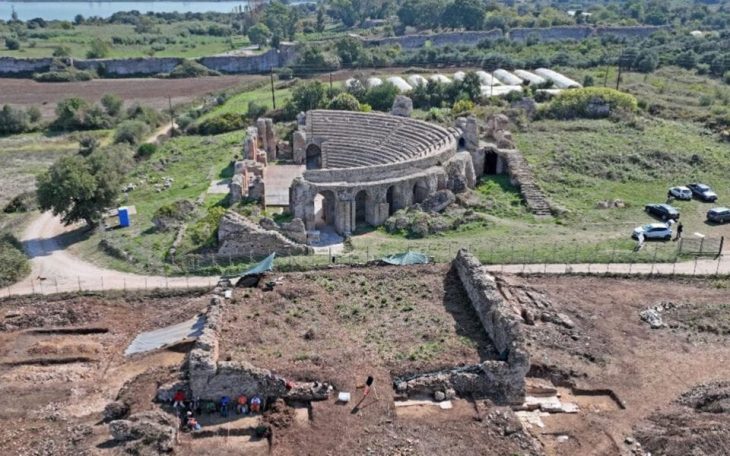

The South Caucasus, rich in mineral deposits, has long been a crossroads of technological experimentation. Western Georgia’s Colchis region is well known for its massive Late Bronze and Early Iron Age copper smelting industries. Yet Kvemo Bolnisi stands out for its unique integration of settlement, mining, and smelting activities in one place.

Unlike Colchis, where copper was smelted in isolated industrial landscapes and then transported to coastal settlements, Kvemo Bolnisi’s workshop sat directly next to the ore body and within a lived settlement. This proximity may have fostered daily experimentation, including the deliberate addition of hematite.

Implications for the Origins of Iron

The discovery rewrites part of the story of iron’s origins. While Kvemo Bolnisi was not producing iron objects, the habit of adding iron oxides to the furnace charge created the conditions in which metallic iron could have been accidentally or deliberately produced.

If a furnace charge contained less copper and more hematite—and if reducing conditions were intensified—then usable metallic iron might have been formed. Such scenarios make it increasingly plausible that iron metallurgy emerged not in isolation but directly out of the practices of copper smelters.

This supports a long-discussed but poorly evidenced hypothesis: that iron technology was invented by copper workers who were already experimenting with the redox behavior of iron-bearing minerals.

A Cognitive Step Toward the Iron Age

What makes Kvemo Bolnisi so significant is not that it produced iron, but that it demonstrates a new level of metallurgical knowledge. By treating hematite as a separate, functional material, Bronze Age smelters in Georgia showed a grasp of high-temperature processes that went beyond simple ore exploitation.

This was not blind trial and error: it was empirical innovation. In the words of the researchers, it reflects “an ability to control and manipulate materials to achieve a desired result”—a hallmark of true technological progress.

Global Parallels and the Wider Picture

Other cases of intentional fluxing in copper smelting are known—from Timna in the Levant, to Peru and even Iron Age South Africa—but most are later in date or less conclusive in demonstrating deliberate practice. Kvemo Bolnisi now stands as the earliest unequivocal evidence of iron oxide fluxing in copper metallurgy, predating 500 BC.

By showing that Bronze Age metallurgists in the Caucasus were already experimenting with hematite more than 3,000 years ago, the study provides a missing link in the long and complex story of iron invention.

Conclusion

The findings from Kvemo Bolnisi underscore the creativity and experimental mindset of ancient metallurgists. Far from passive workers bound by tradition, they were active innovators, probing the boundaries of materials science millennia before the term existed.

Iron may not have been the intended product at Kvemo Bolnisi—but the seeds of the Iron Age were arguably sown in its furnaces.

Erb-Satullo, N. L., & Klymchuk, B. W. (2025). Iron in copper metallurgy at the dawn of the Iron Age: Insights on iron invention from a mining and smelting site in the Caucasus. Journal of Archaeological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2025.106338

Cover Image Credit: Reconstruction of a Bronze Age smelting workshop in Georgia, where metallurgists experimented with hematite, a practice that helped spark the dawn of the Iron Age. AI-generated illustration. Credit: Arkeonews