Hidden beneath the sands of time in the tranquil Morphou Bay lies Agia Eirini (Turkish: Akdeniz), a seemingly quiet village in the Kyrenia district that holds one of the Mediterranean’s most astonishing archaeological treasures: the Agia Eirini Terracotta Army. Often overshadowed by its Chinese counterpart, this lesser-known yet equally fascinating collection of ancient figures paints a vivid picture of Cypriot religious and cultural life from over 2,500 years ago.

Located near the northwestern coast of Cyprus, in the Kyrenia district overlooking the scenic Morphou Bay, the small village of Agia Eirini (known today as Akdeniz) lies within the territory currently under the de facto control of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

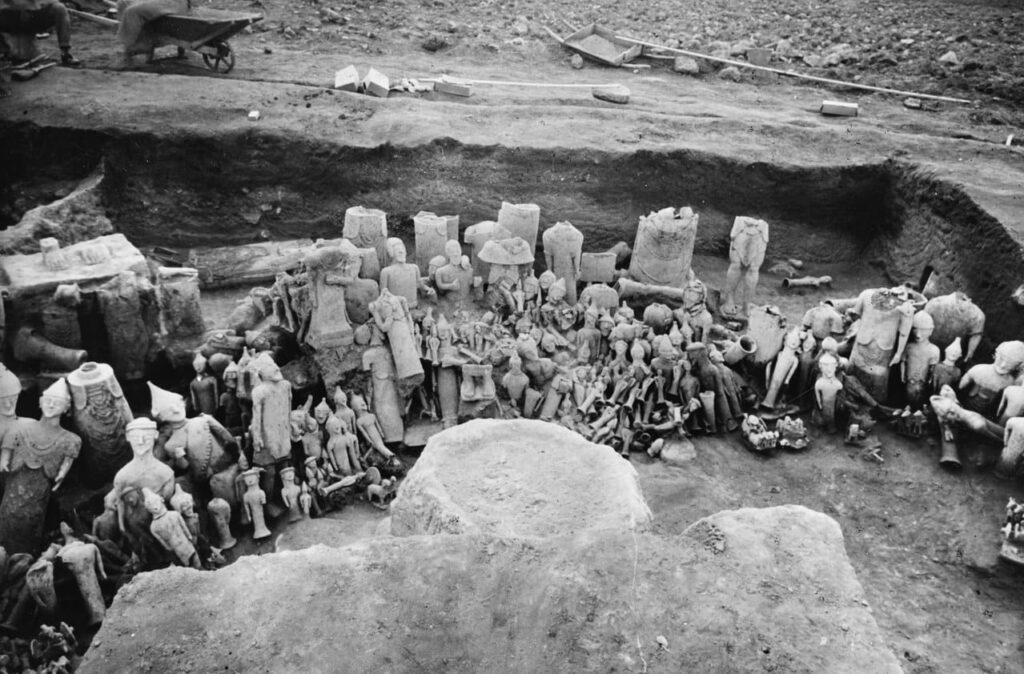

Discovered in 1929 by the Swedish Cyprus Expedition, led by archaeologist Einar Gjerstad, the sanctuary at Agia Eirini has yielded over 2,000 terracotta sculptures dating from the 7th to 6th centuries B.C., representing a remarkable continuity of sacred traditions and artistic craftsmanship.

The Accidental Discovery That Changed Cypriot Archaeology

The story began when a local priest, Papa Prokopios, intercepted a looter on his farmland and presented a fragment of a stolen statue to the museum in Nicosia. This prompted the Swedish team to launch an excavation that would reveal not just an ancient temple, but an entire religious complex used continuously from the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1200 B.C.) to the Cypro-Archaic period (ca. 500 B.C.).

Just half a meter below the surface, archaeologists uncovered a semicircular arrangement of terracotta statues, depicting priests, warriors, musicians, and animals. These figures, some life-sized and intricately detailed, stood as silent sentinels to a forgotten deity.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The sculptures are on display at the Medelhavsmuseet (Museum of Mediterranean Antiquities) in Stockholm. Photo credit: Notafly / Public Domain

Artistry Influenced by Empires

Experts suggest the figures demonstrate stylistic influences from Assyrian, Phoenician, and Minoan cultures, visible in their attire, posture, and symbolic accessories. Some warrior statues bear horned helmets and exaggerated musculature reminiscent of Assyrian guardian spirits, while others reflect Greek kouroi stylization with their rigid postures and almond-shaped eyes.

Notably, the bull-headed priest figurines and libation vessels with mythological motifs echo Minoan and Mycenaean iconography, suggesting that the cult may have absorbed diverse elements from regional trade and migration.

A Sanctuary of Fertility, Warfare, and Ritual Music

Archaeological findings indicate that the sanctuary was dedicated to a fertility deity, likely associated with agricultural abundance and animal husbandry. The abundance of bull effigies, libation tools, and ritual musical instruments such as terracotta tambourines and flutes reveals a dynamic ritual life.

Later phases of the sanctuary included anthropomorphic figures, minotaurs, and warrior-priests, suggesting a shift toward heroic or martial aspects of divinity—possibly tied to regional conflicts or changing political ideologies.

A unique feature was the presence of sacred enclosures for trees, a direct nod to Minoan sacred groves, further emphasizing the syncretic nature of the Cypriot religion.

Sacrifices and Symbolism: Clues from Ashes and Altar

Charred remains and ash layers atop stone altars point to blood sacrifices, a practice that added a visceral dimension to the temple rituals. The altars were later displaced during reconstruction, with offerings reverently reburied nearby—a testament to the evolving yet persistent nature of local faith.

At the center of worship may have stood a sacred stone or betyl, an aniconic symbol of the divine that persisted across successive phases of the temple’s use.

From Obscurity to International Fame

After being forgotten for centuries beneath agricultural fields, the sanctuary’s discovery not only transformed the archaeological map of Cyprus but also sparked international collaboration. In 1931, half of the statues were sent to Stockholm’s Medelhavsmuseet, where they remain a centerpiece of Mediterranean antiquities. The remaining figures are housed in the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia (Lefkoşa), proudly representing the island’s rich prehistoric narrative.

Though the true identity of the deity remains unknown, the Agia Eirini sanctuary continues to captivate scholars and visitors alike. It serves as a reminder of the island’s pivotal role in the crossroads of ancient civilizations, and the enduring power of art to preserve spiritual memory.

Source: Medelhavsmuseet (Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm) Online archive: Medelhavsmuseet’s digital collection

Swedish Cyprus Expedition: Finds and Results of the Excavations in Cyprus 1927–1931, Vol. 1 (1934)

Swedish Cyprus Expedition: Finds and Results of the Excavations in Cyprus 1927–1931, Vol. 2 (1935)

Swedish Cyprus Expedition: Finds and Results of the Excavations in Cyprus 1927–1931, Vol. 3 (1937)

Cover Image Credit: The terracotta statues of Agia Eirini at the Medelhavsmuseet in Stockholm. Credit: Margareta Sjöblom / Public Domain