Archaeologists have uncovered a little-known knife collection revealing that Xiongnu-era blacksmithing traditions survived along the Yenisei River for more than 1,000 years, from antiquity to the Middle Ages.

New archaeological research indicates that communities living along Siberia’s Yenisei River preserved metalworking traditions rooted in the era of the Xiongnu nomads for more than a thousand years—long after those techniques vanished elsewhere across Eurasia. The findings shed new light on the cultural resilience of taiga societies and the long afterlife of steppe technologies beyond the fall of ancient nomadic powers.

The study was carried out by researchers from Siberian Federal University, who re-examined a rare but largely forgotten group of iron artifacts held in the collections of the Yeniseisk Museum-Reserve named after A. I. Kytmanov. Many of the objects entered the museum as early as the late 19th century but, until now, had never been fully documented or studied in a modern archaeological framework.

Knives That Defied Time

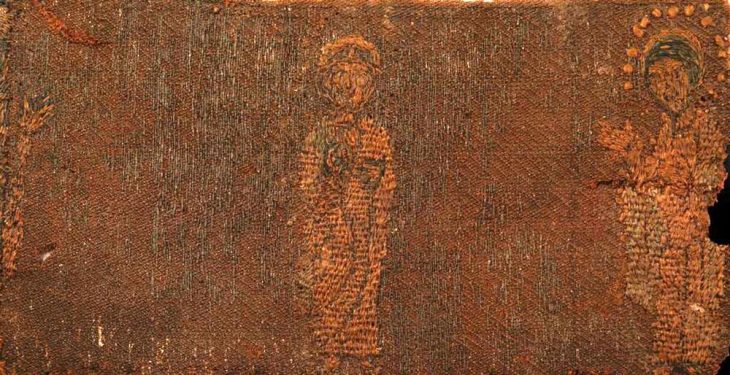

At the core of the research is a collection of 17 iron knives recovered from sites across the Yenisei region. Several of these blades display a striking and rare feature: a pommel formed as a loop or ring. This design is well known to archaeologists as a hallmark of metalworking traditions that emerged during the Xiongnu period, roughly between the 2nd century BC and the 2nd century AD.

Across most of Eurasia, knives with ring-shaped pommels disappear after the collapse of Xiongnu political dominance. In the Yenisei taiga, however, the idea endured. According to the researchers, such knives continued to be manufactured and used locally until the 11th–14th centuries, a survival unmatched in neighboring regions of Siberia or Central Asia.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The blades themselves vary in size and form, indicating everyday use rather than ceremonial display. Many show traces of fire exposure, including scale and oxidation, suggesting that they originated from disturbed or destroyed burial contexts rather than settlement layers.

From Fieldwork to Museum Archives

The breakthrough did not come from a new excavation campaign in the taiga, but from painstaking work inside museum archives. As Polina Sentorusova, senior researcher at the Laboratory of Archaeology of Yenisei Siberia, explained, archaeological discovery is not always about remote field expeditions.

“Archaeological expeditions are not always journeys into the taiga, mountains, or swamps,” Sentorusova noted. “Sometimes, the most valuable material is found by visiting small regional museums and carefully re-examining old collections.”

It was precisely through this kind of archival research that the team was able to assemble, systematize, and publish a collection of 17 iron knives that had remained largely unstudied since their acquisition by the museum in the late 19th century. Many of the blades bear clear traces of exposure to fire, including heavy scaling, suggesting that they likely originated from burial contexts that were later disturbed or destroyed.

From Museum Storage to Scientific Record

The breakthrough did not come from a new excavation, but from careful work inside museum storage rooms. Researchers digitized the artifacts, revisited archival records, and reconstructed the circumstances under which the knives were originally collected more than a century ago.

This approach allowed scholars to trace how blade shapes evolved over time, from the Xiongnu era through the Migration Period and into the developed Middle Ages. Such long-term continuity is rare in archaeological material and provides an important chronological tool for dating other, less well-preserved finds in the region.

The collection is now recognized as one of the largest and most informative assemblages of iron knives from the Yenisei area, significantly expanding knowledge of everyday life in Siberia’s medieval taiga.

Who Were the Xiongnu?

The Xiongnu were a powerful nomadic confederation that emerged in the late 3rd century BC across the степpe regions of northern China and southern Siberia. Often described as the first great nomadic empire of Inner Asia, they built a complex political system based on mobile pastoralism, long-distance trade, and advanced military organization.

Chinese historical sources portray the Xiongnu as formidable rivals of the Han dynasty, prompting the construction and expansion of early frontier defenses later incorporated into the Great Wall. After the decline of their confederation, parts of the Xiongnu population are believed to have migrated westward, contributing—directly or indirectly—to the emergence of the Huns known from European history.

What this new study highlights is not migration, but legacy. The persistence of Xiongnu-style metalworking along the Yenisei suggests that technological knowledge could outlast political structures by many centuries when embedded in local craft traditions.

A Cultural Island in the Taiga

One of the most striking aspects of the findings is their geographical isolation. Medieval sites neighboring the Yenisei basin show no comparable knives, indicating that these blacksmithing traditions survived within a limited cultural corridor rather than spreading outward.

For archaeologists, this makes the Yenisei region a rare case study of long-term technological continuity. It also challenges the assumption that nomadic innovations vanished quickly after the collapse of steppe empires.

Instead, the research points to a quieter story: small, forest-based communities selectively preserving and adapting ancient ideas that remained practical in their environment. In doing so, they became the last custodians of a metallurgical tradition that once stretched across much of Inner Asia.

Cover Image Credit: Siberian Federal University