For centuries, one of the most important cities of the ancient world lay hidden beneath dust, war zones, and shifting rivers. Alexandria on the Tigris—once a thriving center of long-distance trade connecting Mesopotamia with India and beyond—vanished from historical memory after late antiquity. Now, an international research team led by Professor Stefan Hauser of the University of Konstanz has successfully rediscovered and reinterpreted this lost metropolis, revealing its crucial role in ancient global commerce.

A City Founded by Alexander the Great

In the 4th century BCE, Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Persian Empire, reshaping the political and economic landscape of the ancient Near East. Historical sources describe his return journey from the Indus Valley to Mesopotamia, where he planned to travel by water from Susa to Babylon. During this journey, Alexander recognized a strategic problem: heavy sedimentation in southern Mesopotamia was gradually pushing the coastline of the Persian Gulf farther south, making existing harbors unusable.

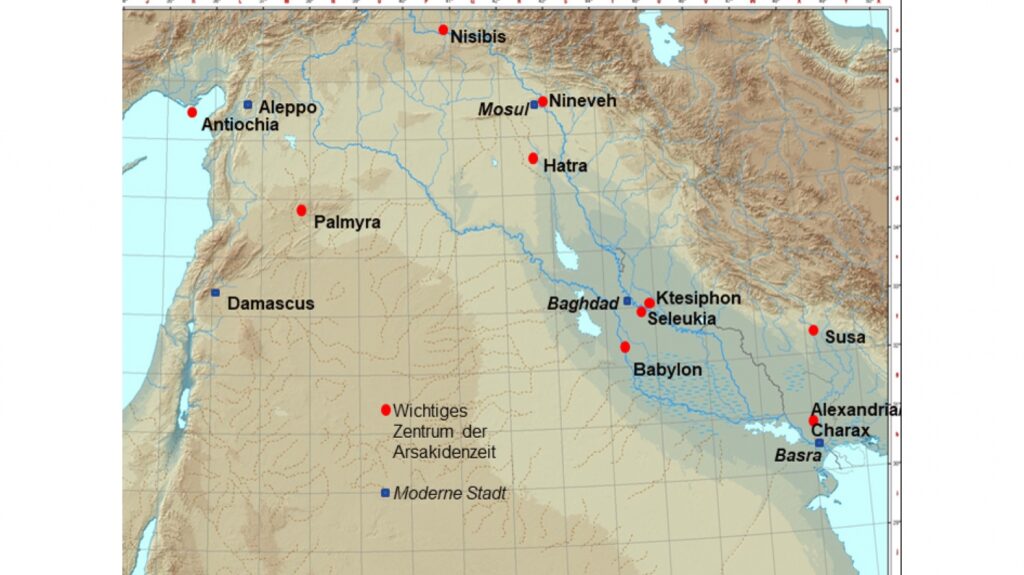

To solve this, Alexander founded a new port city—Alexandria on the Tigris—near the confluence of the Tigris River and the Karun River, approximately 1.8 kilometers from the ancient coastline. Later known as Charax Spasinou or Charax Maishan, the city was mentioned by Roman authors and referenced in inscriptions found as far away as Palmyra in Syria. Despite these clues, its exact location remained uncertain for centuries.

Rediscovering a Lost Metropolis

The first modern hint came in the 1960s, when British researcher John Hansman identified massive settlement outlines and city walls in Royal Air Force aerial photographs. However, due to political instability and armed conflict near the Iranian border, further research was impossible for decades. The site—now called Jebel Khayyaber—was even used as a military camp during the Iran-Iraq War.

Only in 2014 did foreign archaeological missions cautiously return to southern Iraq. British archaeologists working near the ancient city of Ur were guided to Jebel Khayyaber by local authorities. Despite heavy security restrictions, the team was astonished by the scale of the ruins: a massive city wall stretching for kilometers and still rising up to eight meters high in places.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

By 2016, a formal research campaign began, and shortly afterward, Stefan Hauser—one of the world’s leading experts in Hellenistic Near Eastern archaeology—joined the project.

Mapping a Megacity Without Excavation

Due to ongoing security concerns, the researchers initially relied on non-invasive methods. Over several years, they conducted extensive surface surveys, covering more than 500 kilometers on foot and documenting thousands of pottery shards and brick fragments. Drone photography allowed the team to construct a detailed digital terrain model, revealing the astonishing truth: Alexandria on the Tigris was a massive, carefully planned metropolis.

Hauser describes it as the eastern counterpart to Alexandria in Egypt. Both cities were founded at the meeting point of river systems and maritime trade routes, functioning as gateways between inland regions and the open sea. For more than 550 years, Alexandria on the Tigris served as one of the most important hubs of ancient long-distance trade.

Streets, Temples, and Industrial Zones

Geophysical surveys played a key role in reconstructing the city’s layout. Using cesium magnetometers, researchers detected streets, walls, canals, and even industrial installations without disturbing the soil. The results revealed some of the largest residential blocks known from antiquity, arranged in a systematic grid extending kilometers beyond the city’s northern wall.

However, the grid was not uniform. Archaeologists identified at least four different orientations, indicating multiple construction phases and functional zones. The city included extensive residential areas, monumental temple complexes, workshop districts with kilns and smelting furnaces, an inner-city harbor connected to canals, and even a palace-like complex possibly surrounded by gardens or agricultural land.

Satellite imagery also revealed a vast irrigation system north of the city, suggesting large-scale grain production to support the population.

Still impressive today: the fortification walls of Alexandria. Credit: © Charax Spasinou Project – Stuart Campbell, 2017

A Key Node in Ancient Global Trade

Between 300 BCE and 300 CE, trade between Mesopotamia and India intensified dramatically, with connections reaching Afghanistan and China. During this period, the great twin cities of Seleucia and Ctesiphon emerged along the Tigris as imperial capitals. Ancient sources estimate Seleucia’s population alone at up to 600,000—creating enormous demand for imported goods.

According to Hauser, nearly all trade from India passed through Alexandria on the Tigris. Even when newer ports were built farther south due to ongoing sedimentation, goods were still transshipped through this city first. Its strategic location made it indispensable—until nature intervened once again.

Decline, Abandonment, and Legacy

The city’s fate was tied to the river that sustained it. Geological studies show that the Tigris gradually shifted westward, cutting Alexandria off from its waterway. By the 3rd century CE, the city lay far from both the river and the Persian Gulf, which had retreated nearly 180 kilometers south.

Without river access, Alexandria on the Tigris lost its economic and political significance and was eventually abandoned. Its legacy, however, lived on. The modern city of Basra would later inherit its role as the region’s primary port.

Today, thanks to funding from the Gerda Henkel Foundation, the German Research Foundation (DFG), and the British Council’s Cultural Protection Fund, further excavations are planned. As Professor Hauser notes, Alexandria on the Tigris still has many secrets left to reveal—and its rediscovery is reshaping our understanding of ancient globalization.

Cover Image Credit: Charax Spasinou Project 2022 (Robert Killick)