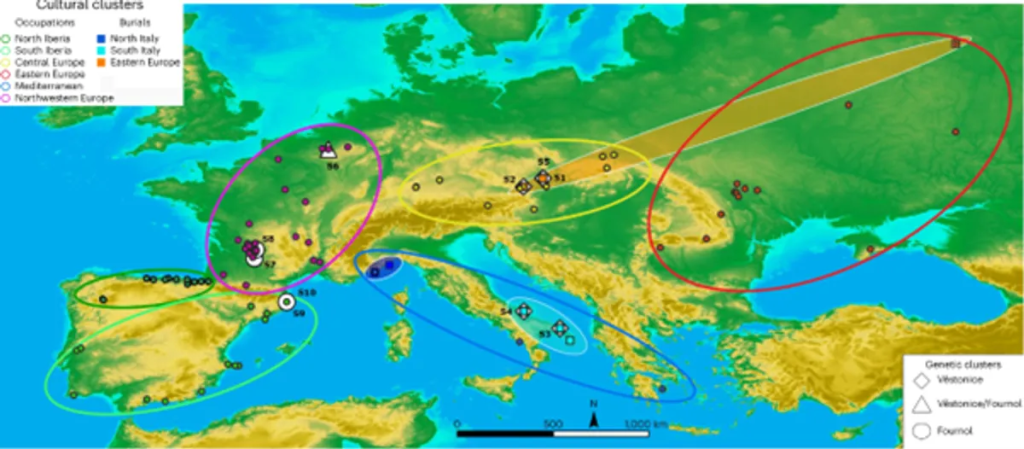

In a new study, researchers have constructed a continent-wide database of personal ornaments worn by Europeans 34,000-24,000 years ago, a period known as the Gravettian technocomplex. Combining the locations at which these were found with genetic data revealed nine distinct cultures.

For ice age hunters in Europe some 30,000 years ago, styles of ornaments including amber pendants, ivory bangles, and fox tooth beads may have also signaled membership in a particular culture, researchers report in Nature Human Behaviour.

The geographic distribution of the beads and the distinctive qualities of their styles serve as the basis for these classifications. In order to highlight the geographic dispersion of these hunter-gatherers throughout Europe, researchers have assembled a new dataset of personal ornaments worn by Europeans during this time.

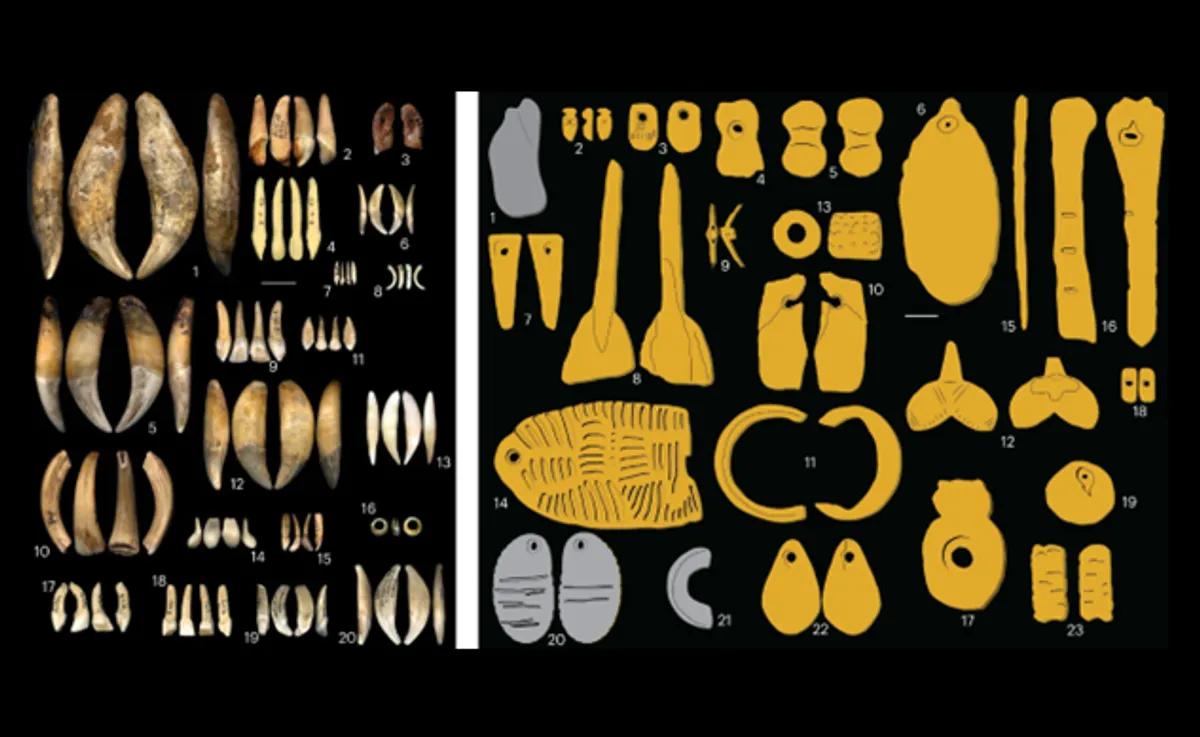

Researchers looked at 134 different kinds of ornaments that were gathered over the course of the previous century from 112 sites in Europe by archaeologists. This large dataset gave a thorough overview of the wide variety of beads that the Gravettians used. Through database integration and data integration from earlier scientific studies and literature, the researchers were able to distinguish and evaluate the distinctive qualities and differences among the bead types linked to various cultural groups.

These ornaments had previously been grouped together as a single culture, the Gravettian people, based on their age and other related artifacts. Best known for their venus figures, including the Venus of Willendorf, this widespread population thrived across Europe for around 10,000 years before dying out before the peak of the last ice age.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

But the diversity of ornaments, once collated en masse, was striking. The researchers identified 134 different types of beads that the Gravettians had crafted from animal bones, teeth, shells, amber, and stone. Some resembled fishtails; others owls. While most of the trinkets were found in the ruins of Gravettian dwellings, some were excavated from burial sites where DNA samples had also been collected.

“We started noticing differences as we were making the database,” study lead author Jack Baker, a doctoral student of prehistory at the University of Bordeaux in France. “There’s actually a big difference, especially between the west and the east.”

Researchers compared bead types between sites and found that places with similar accouterments clustered geographically. Nine distinct groups emerged. People at the easternmost sites, such as Kostenki along the Don River in Russia, seemed to prefer ornaments made of stone and red deer canines, whereas those in northwest Europe wore tube-shaped shells of Dentalium mollusks.

The Gravettian was not “one monolithic thing,” Baker says, but instead included several culturally distinct groups, each hewing to their own ornamental traditions. His team thinks these groups crossed paths: The team’s computer simulations suggest the patterns of bead differences most resemble a scenario in which neighboring groups occasionally swapped styles or territories.

This observation suggests that various factors beyond genetic heritage influenced the distinctiveness of these cultures, including the availability of materials, cultural exchanges among different groups, and individual social status within their respective communities. The study revealed that these differences were particularly pronounced in the context of burial sites, as opposed to the places where people lived.

According to Baker, “Cultural differences crystallize better around things like funerary rites.” Practices related to burial and mortuary rituals played a significant role in delineating the cultural identities and social dynamics of Gravettian populations.

For instance, burials were a common cultural practice among Early and Middle Gravettian populations in Eastern Europe. However, as the Gravettian period progressed, there was a notable shift away from burying the deceased, indicating an evolution of social norms within Gravettian societies over time.

In comparing their findings with up-to-date palaeogenetic data, the researchers discovered both agreements and discrepancies. While some alignment between cultural and genetic data was observed, the cultural analysis revealed nuances and complexities not captured by genetic studies alone. Specifically, the presence of cultural entities in regions not yet sampled by genetic research suggests the existence of cultural diversity beyond the scope of current genetic datasets, reports Scientific American.

As an illustration of their findings, researchers observed that despite the widespread availability of foxes and red deer across the continent during the Gravettian period, these animals were selectively incorporated into beads by specific cultural groups. This suggests that certain Gravettian communities possessed distinct preferences or cultural practices related to the use of specific animal materials in bead making.

Researchers were able to confirm the existence of most cultural groups identified in the archaeological record by comparing them with existing genetic data. However, they encountered challenges in identifying one specific eastern European group due to the lack of known genetic data available for that region. Additionally, two cultural groups in Iberia were only supported by genetic data from a single individual, further complicating the analysis.

For Baker, the research also serves as a reminder that even during the harsh conditions of an ice age, human creativity and cultural expression flourished, with prehistoric populations continuing to create objects of beauty to adorn themselves. The study also serves as an anthropological insight into the resilience and creative spirit of our ancestors.

Cover Photo: J. Baker, et al/Nature