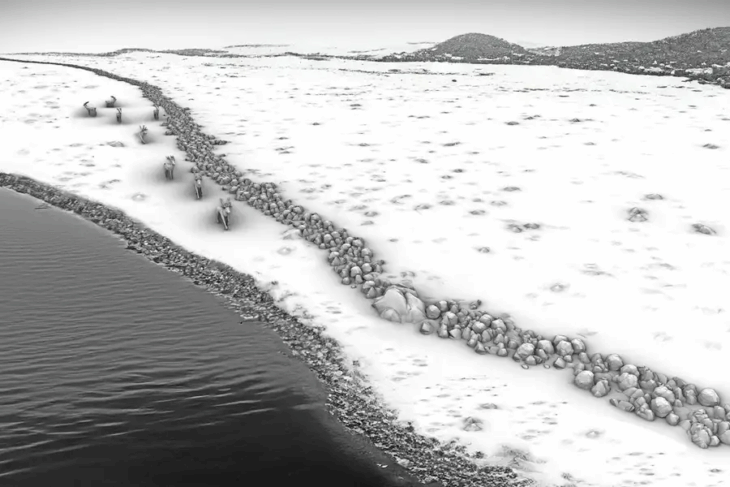

In a rare and captivating discovery, archaeologists have uncovered ancient human footprints dating back approximately 7,000 years at the site of Tell Kurdu Höyük (Kurdu Mound), located in the Amuq Plain of southern Türkiye’s Hatay province, near the Syrian border. The footprints, believed to date to around 5200 BCE during the Ubaid Period, were found preserved in a water-saturated clay layer, and offer a vivid connection to life in prehistoric Anatolia.

The Discovery

According to a statement by Türkiye’s Minister of Culture and Tourism, Mehmet Nuri Ersoy, excavations at Tell Kurdu revealed five human footprints in strata dated to 5200 BCE. The impressions appear to have been left by individuals walking across wet, clay-rich ground — likely soon after rainfall or in marshy conditions. This exceptional find, the minister noted, provides “an unparalleled witness” to human presence in Anatolia millennia ago.

The footprints were uncovered on August 21, 2025, in what is designated as “excavation unit 8564.” The team interprets the prints as belonging to people traversing a “clayey fill layer” exposed to heavy moisture. Such preserved footprints are extremely rare in Anatolian archaeology, especially from such an early era.

Tell Kurdu: A Window into the Chalcolithic

Tell Kurdu is one of the major prehistoric settlement mounds of the Amuq Plain, situated between Anatolia, northern Mesopotamia, and the Levant — a crossroads of ancient cultural interaction.

The Tell Kurdu Excavation Project is co-directed by Rana Özbal (Koç University) and Fokke Gerritsen (Netherlands Institute in Turkey). Renewed excavations since 2022 aim to explore the often-overlooked Middle to Late Chalcolithic period (sixth to fifth millennium BCE).

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Archaeologically, Tell Kurdu is valuable because it preserves horizontal exposures spanning both the 6th and 5th millennia BCE, including phases tied to Halaf and Ubaid cultural influence.

Early trenching has revealed architectural remains (walls, streets, courtyards) as well as evidence for ceramic production and craft workshops in Ubaid-era levels.

One challenge at the site is that earlier “mounding” and bulldozing have disturbed upper levels; in places, later occupation strata were truncated, so intact Ubaid-level deposits lie just a few centimeters below the modern surface.

Tell Kurdu also interacts with broader regional networks: for example, obsidian sourcing studies show materials at the site originated from multiple Anatolian and near-Mesopotamian sources, reflecting trade and exchange ties in both Halaf and Ubaid phases.

The Ubaid Period: Cultural Reach and Local Adaptation

The Ubaid Period (roughly c. 5500–3700 BCE in southern Mesopotamia, though in northern zones often narrower) marks one of the earliest cultural horizons across Mesopotamia and its peripheries.

It is characterized by distinctive painted, buff-ware ceramics, as well as the spread of architectural forms, communal rituals, and early craft specialization.

In Anatolia and the Amuq region, the Ubaid influence is adapted in local terms: at Tell Kurdu, the fifth-millennium (Amuq E) levels show clear Ubaid-style ceramics and structural features, but with continuity in population and local traditions.

Some burials even align with Ubaid mortuary practices, including the use of separate cemetery zones rather than household interments.

At the same time, genetic and anthropological data suggest population continuity through the transition from Halaf-related to Ubaid influence — meaning the cultural shift was less about large migrations and more about adoption and interaction.

Tell Kurdu thus serves as a kind of “local lens” through which archaeologists can examine how Ubaid trends spread into Anatolia, and how local communities negotiated those wider currents while retaining identity.

Significance of the Footprint Find

Footprints preserved from so long ago are extraordinarily rare, especially in Anatolia. These five human imprints — frozen in time — bring a tangible immediacy to prehistoric everyday life, hinting at movement, presence, and environment in a way that pottery shards or walls alone cannot.

Moreover, their context — wet clay, a moment in time — reminds us how precarious the conditions are for preserving such traces over millennia. Their survival underscores the importance of careful excavation, stratigraphic control, and prompt documentation.

As excavations continue, archaeologists hope to discover further clues about the individuals who left these footprints: their age, gait, number of people walking together, and the broader setting of that moment in the Ubaid-era settlement.

Looking Ahead

Under the “Geleceğe Miras” (Heritage for the Future) initiative, Turkey aims to accelerate archaeological research and protect heritage sites nationwide. In that spirit, the Tell Kurdu team is advancing work at multiple trenches, especially targeting Ubaid-level exposures near the mound crest and the eastern sectors.

With each new season, the discovery of these footprints invites readers and scholars alike to imagine — for a fleeting instant — the living presence of people in Anatolia some 7,000 years ago, walking in wet clay, leaving traces that would survive to the present day.

Cover Image Credit: Photo courtesy of Minister Mehmet Nuri Ersoy, via social media.