Archaeologists in Iran have uncovered a rare Sassanid-era rock inscription that sheds new light on royal festivals and calendrical traditions practised during late antiquity. The inscription, recently identified on rock cliffs in the Marvdasht Plain in southern Iran, is believed to reference a ceremonial event held during the month of Dey, a significant period in the ancient Iranian calendar.

According to Iranian archaeologist and historian Abolhassan Atabaki, the small stone inscription was carved in Middle Persian (Pahlavi) script and appears to record the date of an official Sassanid celebration. Although parts of the text have been damaged by erosion over centuries, surviving lines clearly point to a royal festival associated with Dey, one of the winter months in the Zoroastrian calendar.

“The inscription most likely commemorates the timing of a Sassanid royal ceremony,” Atabaki explained in remarks to the Tehran Times, noting that weathering and natural erosion have caused the final portion of the text to be lost. Despite this damage, the find is considered archaeologically valuable due to the scarcity of inscriptions that directly reference festivals rather than royal titles or victories.

The month of Dey held special religious and symbolic importance in pre-Islamic Iran. In the Zoroastrian calendar, Dey is associated with Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity, and includes several important observances such as Deygan festivals, which were celebrated on days when the name of the day and the month coincided. These festivals emphasized royal legitimacy, cosmic order, and the divine protection of kingship—core concepts in Sassanid political ideology.

The Sassanid Empire (224–651 CE) placed strong emphasis on ritual, calendar regulation, and religious ceremonies as tools of governance. Royal festivals were not merely social events but were closely tied to state ideology, reinforcing the king’s role as the protector of faith and order. Inscriptions referring to such events suggest that ceremonies were sometimes commemorated in public or sacred landscapes, particularly near historically significant sites.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

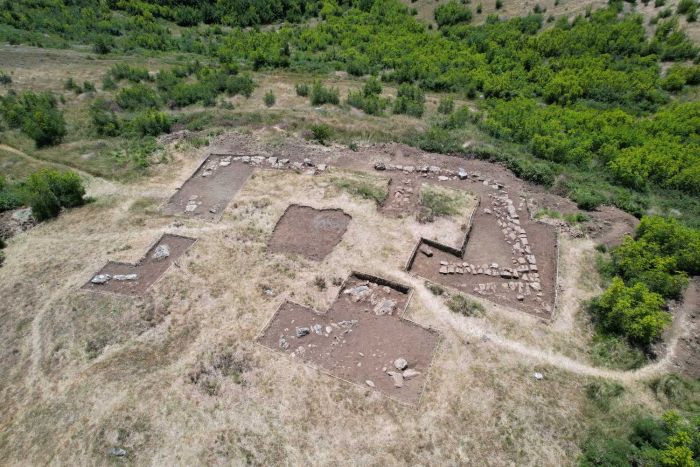

The Marvdasht Plain is one of Iran’s most archaeologically rich regions, hosting remains from multiple ancient civilizations. Over the past two years, Atabaki has documented several additional Sassanid-era carvings in the area, many of them etched into limestone cliffs overlooking ancient routes and settlements.

According to Atabaki, more than 50 historical remains from the Elamite, Achaemenid, and Sassanid periods have been recorded across the plain. These findings include inscriptions, rock reliefs, and architectural traces that collectively illustrate the area’s continuous importance over several millennia.

Marvdasht is located near some of Iran’s most iconic ancient sites, including Persepolis, the ceremonial capital of the Achaemenid Empire, as well as Naqsh-e Rostam and Naqsh-e Rajab, both renowned for their royal tombs and reliefs spanning multiple dynasties. The nearby ruins of Estakhr, a major city during the late Achaemenid and Sassanid periods, further highlight the region’s enduring political and religious significance.

Archaeological research indicates that settled communities existed on the Marvdasht Plain long before Achaemenid king Darius I selected the foothills of Mount Rahmat for the construction of Persepolis in the 6th century BCE. The continued use of the landscape during the Sassanid era demonstrates how later empires consciously linked themselves to Iran’s imperial past.

Scholars believe that discoveries such as this newly identified inscription contribute to a deeper understanding of Sassanid ceremonial life and the role of seasonal festivals in reinforcing imperial authority. Further documentation and preservation efforts are expected to provide additional insights into how ancient Iranian rulers used ritual, timekeeping, and sacred geography to legitimize their rule.

Cover Image Credit: Tehran Times