Shipwreck site near Île Sainte-Marie matches historical records of pirate Olivier Levasseur’s treasure-laden vessel, say researchers

After more than fifteen years of underwater exploration and archaeological excavation, researchers believe they may have discovered the remains of one of the most legendary pirate ships in history: the Nossa Senhora do Cabo, captured by the infamous pirate Olivier Levasseur, also known as “La Buse,” in 1721.

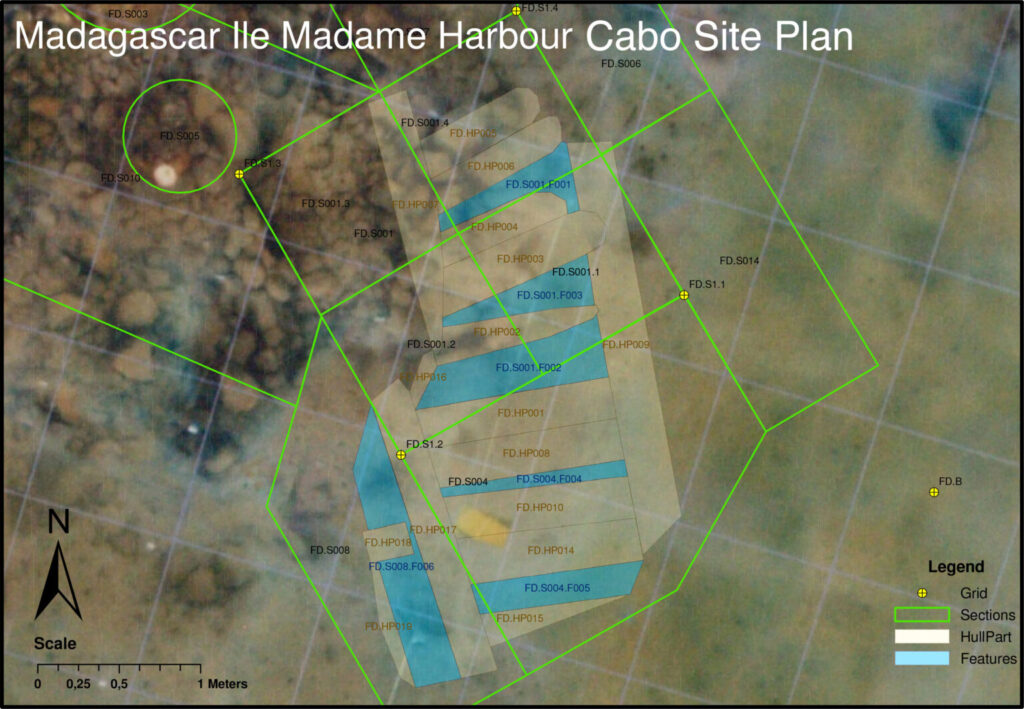

Located off the small island of Îlot Madame, near Madagascar’s eastern coast, the shipwreck site has yielded a remarkable trove of artifacts, ship timbers, and structural features consistent with 18th-century Portuguese East Indiaman construction. Combined with detailed historical records, the evidence points to a compelling case that this may indeed be the long-lost vessel that once carried one of the richest pirate treasures ever recorded.

A Legendary Capture in the Indian Ocean

Historical documents recount how La Buse and fellow pirate John Taylor seized the Nossa Senhora do Cabo—originally a 72-gun Dutch-built man-of-war—near Réunion Island in April 1721. The vessel had been sailing from Goa to Lisbon, carrying an immense cargo of gold, silver, jewels, silks, and religious artifacts, as well as over 200 enslaved individuals bound for sale in Madagascar.

Following the capture, the pirates reportedly towed the ship to Saint Marie Island, renamed it Victorieux, and careened it for refitting. Eventually, as pirate alliances fractured, the ship was scuttled near Îlot Madame—an area now known as Pirate Island.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

In their paper, which hasn’t been peer reviewed yet, the pair says they have dozens of artifacts that back up their claims.

Archaeological Evidence Emerges from the Depths

Surveys conducted between 1999 and 2015 identified at least ten major anomalies beneath the lagoon, three of which (Anomalies 1, 2, and 6) revealed significant shipwreck features. Among these, Anomaly 1 shows a ballast pile with wooden structural elements, while Anomaly 2 contains articulated timbers and iron fastenings likely from a buried hull.

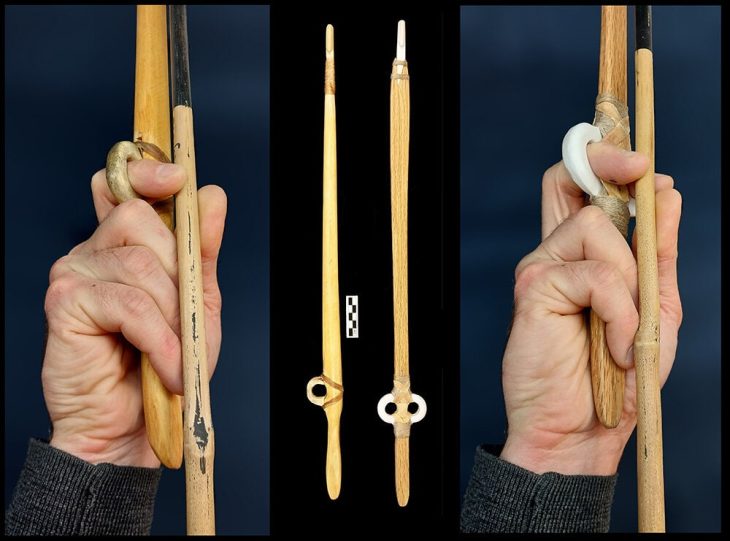

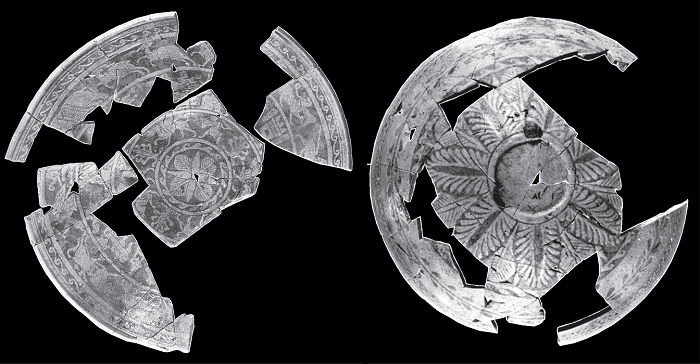

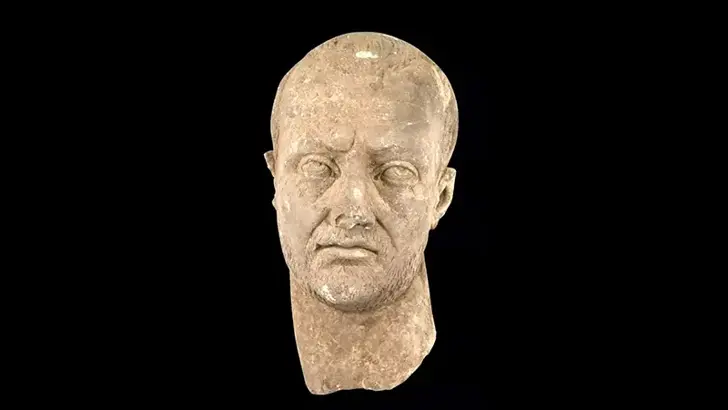

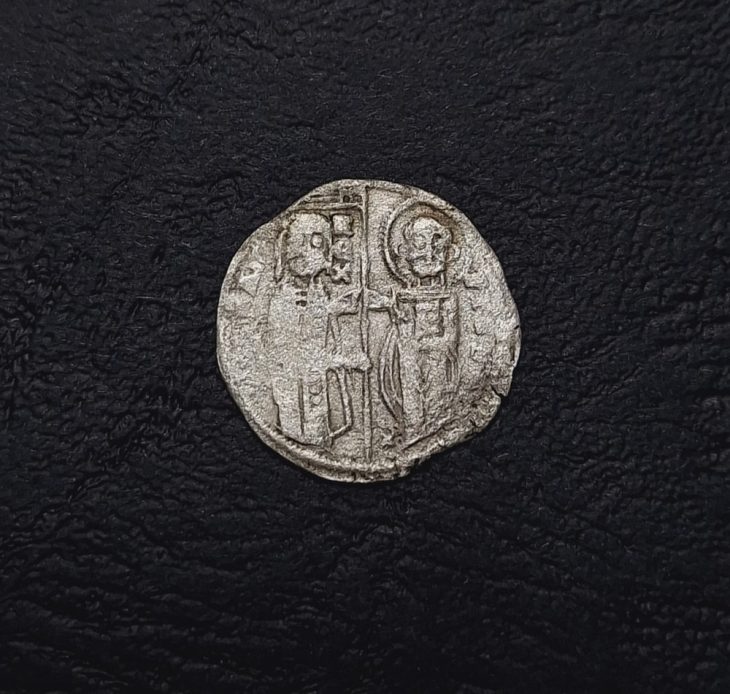

Over 3,300 catalogued artifacts have been recovered from the site, including:

Over 1,500 pieces of 18th-century Chinese porcelain from Jingdezhen

Indo-Portuguese devotional ivory figures and crucifixes

Mughal-period glazed ceramics

Cowrie shells and nutmeg—both key trade items in the Indo-African economy

Gold coins from Dutch, Austrian, and Islamic mints dated between 1649 and 1718

Especially telling is a small ivory plaque engraved with “INRI” and remnants of gold gilding, believed to be part of a Catholic crucifix—strongly suggesting the vessel’s Portuguese religious affiliation.

Structural Clues Support Historical Accounts

Wooden fragments including double futtocks and keel timbers point to a large, ocean-worthy ship. The hull construction aligns with Portuguese East Indiaman shipbuilding techniques of the era, while copper-alloy fasteners and structural reinforcements suggest later modifications—possibly those described in historical records when La Buse reportedly “ripped up half a bridge” to increase the ship’s speed.

Although no nameplate or hull inscription has been discovered, the shipwreck’s size—over 30 meters long—corresponds with 18th-century galleons used in long-distance trade between Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Is This the Victorieux? Evidence Points to Yes

Despite gaps in the archaeological record, the cumulative evidence presents a persuasive narrative. The combined presence of luxury goods, sacred artifacts, military-grade timbers, and geographic consistency with pirate-era descriptions makes this site a strong candidate for the Nossa Senhora do Cabo—the ship later renamed Victorieux by Levasseur.

Dr. Claudio Lorenzo, who led the 2015 field season, noted:

“The integration of physical evidence and historical documentation strongly supports this identification. This site tells a story of piracy, colonial power, and human suffering—etched into the sediment of the Indian Ocean.”

Preservation Challenges and Future Research

The wreck lies in shallow waters within an active lagoon, making it vulnerable to damage from tides, vessels, and chemical erosion. Each excavation season concluded with re-covering the site with ballast stones to preserve the fragile remains. Due to conservation constraints, many artifacts were returned to the seabed after documentation.

Further research is planned to:

Investigate structural changes linked to La Buse’s modifications

Analyze the wood to determine origins from Portuguese and Indian shipyards

Match recovered religious artifacts to known church inventories from Réunion and Goa

Conclusion: A Window into the Golden Age of Piracy

If confirmed, the Nossa Senhora do Cabo represents not just an extraordinary archaeological find, but a rare convergence of piracy, trade, colonialism, and cultural exchange. The ship’s story—carrying treasure, enslaved people, and sacred cargo—embodies the complex dynamics of the 18th-century Indian Ocean world.

The site also reminds us of the human cost beneath the surface: plundered riches, lost lives, and the enduring legacy of imperial exploitation.

Clifford, Brandon A., and Mark R. Agostini, PhD. (2025) “From Goa to Sainte-Marie: An Archaeological Case for the Identification of the Nossa Senhora do Cabo.” Center for Historic Shipwreck Preservation, Brewster, MA.

Cover Image Credit: Pirate ship chasing its prize (unknown artist). Center for Historic Shipwreck Preservation