For more than seven centuries, the violent end of a young medieval nobleman remained an unresolved whisper in European history—half legend, half forensic riddle. His bones, uncovered in 1915 and then lost for decades, carried unmistakable signs of a savage attack. Yet no one could prove who he was, why he was killed, or how his final moments unfolded. Now, a sweeping scientific investigation by Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE) has cracked the case. Through ancient DNA, isotopic analysis, and forensic reconstruction, researchers have confirmed not only the victim’s identity but also the grim choreography of his last minutes.

A single, devastating conclusion emerges from the new evidence: this was a premeditated ambush carried out with extraordinary violence—and science has finally restored the duke who was erased from the political stage in 1272.

A Skeleton Rediscovered, a Mystery Reawakened

The story begins in the sacristy of a medieval monastery, where archaeologists in 1915 uncovered a young man’s skeleton bearing dozens of sharp-force injuries. Early anthropologists proposed a connection to a murdered Hungarian noble, yet the evidence remained too circumstantial to close the case. Worse, the bones vanished from academic view after the 1930s, fueling speculation that they had been destroyed in wartime chaos.

Then came the turning point. In 2018, the postcranial bones resurfaced unexpectedly inside a wooden storage box at the Hungarian Natural History Museum, while the skull—long thought missing—was found preserved at ELTE’s Aurél Török Collection. The rediscovery reopened a century-old forensic puzzle and set the stage for a new investigation supported by anthropologists, archaeogeneticists, stable isotope specialists, radiocarbon experts, and dental researchers.

DNA Reveals the Noble Bloodline

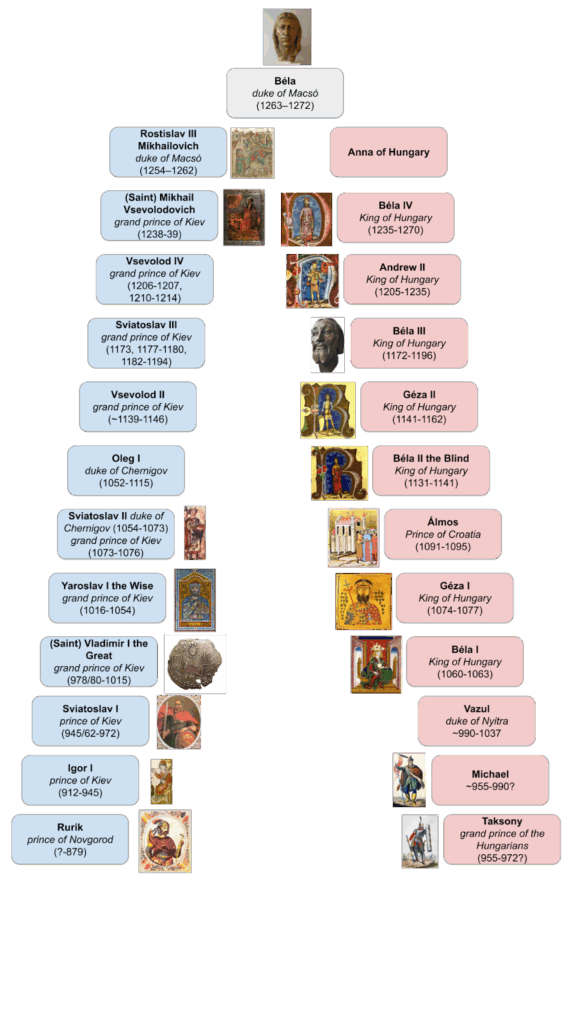

The decisive breakthrough emerged from the genetic analysis conducted by Anna Szécsényi-Nagy and Noémi Borbély of ELTE’s Institute of Archaeogenomics. Whole-genome sequencing aligned the remains exactly with historical genealogies: the young man was a fourth-generation descendant of King Béla III and carried the Y-chromosomal signature of the Rurik dynasty, a lineage of Scandinavian origin that ruled medieval Eastern Europe for centuries.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The genome revealed a complex aristocratic heritage—nearly half Scandinavian, a substantial Eastern Mediterranean component tied to the Byzantine Laskaris family, and a smaller central European element. This genetic mosaic confirmed the identity of the victim: Béla, Duke of Macsó, one of the most politically sensitive figures in 13th-century Hungary. Ancient Origins also highlighted the significance of this identification, noting that apart from King Béla III, he is the only Árpád dynasty member whose nearly complete skeleton has survived.

Tracing the Duke’s Early Life Through Isotopes

Strontium isotope results show the duke spent his early childhood in the region of Vukovar and Syrmia—territory that formed the core of the medieval Macsó Banate. Later in life, he appears to have relocated northward, likely toward the royal court. Radiocarbon analysis initially suggested a slightly earlier date, but further research revealed the influence of a “reservoir effect” caused by heavy consumption of fish and aquatic animals, common in the diet of high-status medieval elites.

His dental calculus contained over a thousand microfossils, including starch grains from wheat and barley that preserved evidence of cooking and baking. Combined, these data reconstruct not only where he lived but how he lived—comfortably, with access to elite food networks, before his abrupt and violent death.

A Forensic Reconstruction of a Savage Assassination

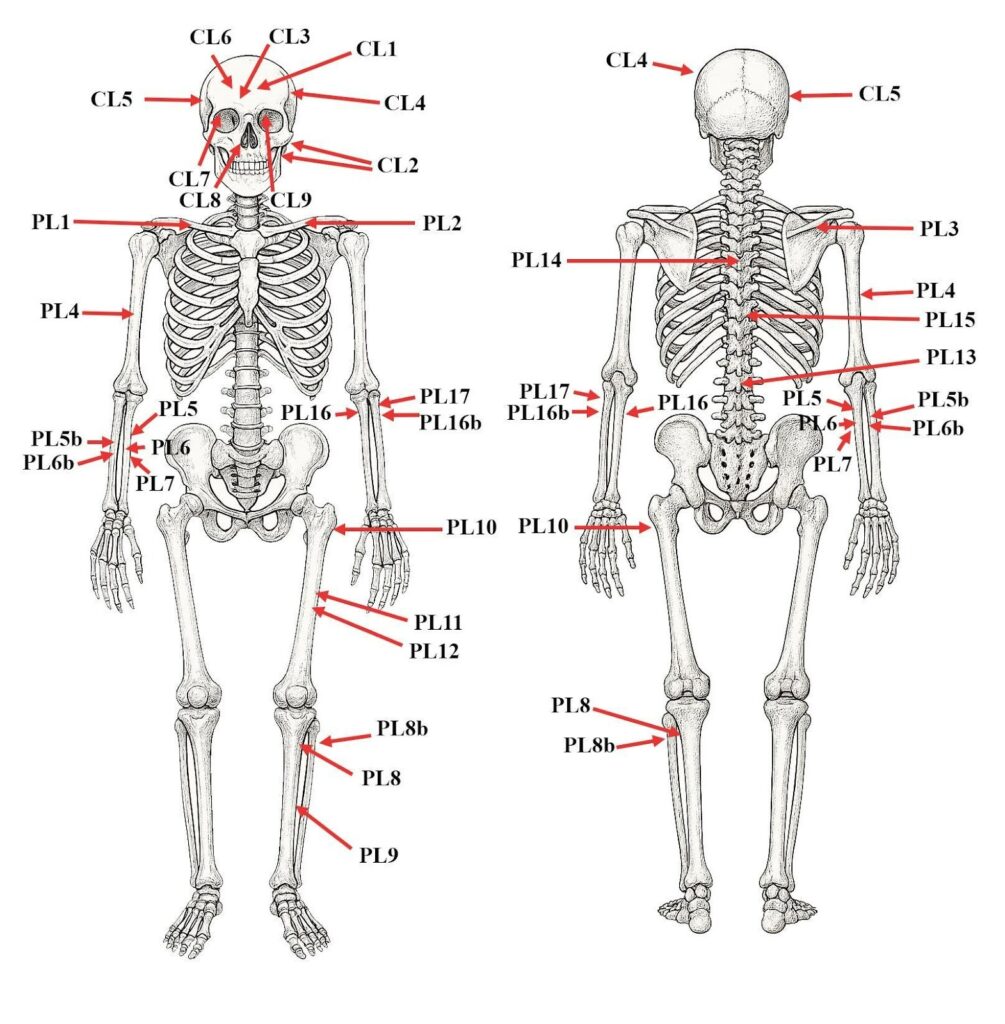

The bones preserve a story far more brutal than the chronicles alone ever hinted. Forensic anthropologists identified twenty-six perimortem injuries—deep cuts, crushing blows, and violent trauma to the skull and limbs. These wounds were inflicted in a rapid, coordinated assault. Three attackers seem to have surrounded Béla: one confronting him head-on, the other two striking simultaneously from his sides.

The depth and angle of the cut marks indicate the use of at least two weapon types, likely a sabre and a longsword. Crucially, the duke was unarmored when attacked, leaving his skull and torso exposed. The pattern suggests he recognized the danger and attempted to defend himself; severe injuries to his hands and arms show last-moment attempts to block incoming strikes.

The reconstructed sequence is chilling. Initial blows targeted the head and upper body. As Béla struggled to protect himself, he suffered defensive wounds. Additional strikes from the sides overwhelmed him, and after he fell, the attackers delivered the fatal blows to his head and face—signs of personal hatred layered atop political motive.

Medieval chronicles had accused the powerful Kőszegi faction of orchestrating the killing, but the forensic evidence now reveals more than simple political elimination. This was a planned ambush executed with rage and precision.

Why This Duke Mattered

Béla of Macsó held a uniquely volatile position in 13th-century Central Europe. Linked to the royal house of Árpád through his mother and to the influential Rurikid network through his father, he embodied a fusion of Western, Byzantine, and Slavic political interests. As Ban of Macsó, he controlled strategic borderlands and possessed legitimate claims to influence at the Hungarian court.

His death in 1272 occurred during a turbulent period marked by rival noble factions competing for dominance over the young King Ladislaus IV. Béla’s assassination removed a powerful political actor—and physics, genetics, and anthropology have now reconstructed exactly how that removal unfolded.

A Medieval Cold Case Finally Closed

According to project leader Tamás Hajdu, the combined evidence leaves no room for ambiguity: the killing was organized in advance, but the execution was far from calm. Béla resisted, suffered multiple coordinated blows, and died in an act of violence that blended political purpose with intense emotional aggression.

Seven hundred and fifty years later, the remains of the forgotten duke speak again. Science has restored his identity, his movements, his diet, and even the brutal rhythm of his final moments—closing one of medieval Europe’s most enduring forensic mysteries.

Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE)

Cover ımage Credit: The skull of the 13th-century individual uncovered in the Dominican monastery on Margaret Island in Budapest, examined in the ELTE-led investigation. Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE)

Hajdu, T., Borbély, N., Bernert, Z., Buzár, Á., Szeniczey, T., Major, I., Cavazzuti, C., Molnár, M., Horváth, A., Palcsu, L., Kelentey, B. Á., Angyal, J., Mende, B. G., Jakab, K., Lisztes-Szabó, Z., Takács, Á., Cheronet, O., Pinhasi, R., Reich, D. E., Trautmann, M., … Szécsényi-Nagy, A. (2025). Murder in cold blood? Forensic and bioarchaeological identification of the skeletal remains of Béla, Duke of Macsó (c. 1245–1272). Forensic Science International: Genetics, 103381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsigen.2025.103381