Archaeologists have uncovered striking evidence of an ancient ceremonial complex in Murayghat, Jordan, that could rewrite what we know about Early Bronze Age ritual life in the southern Levant.

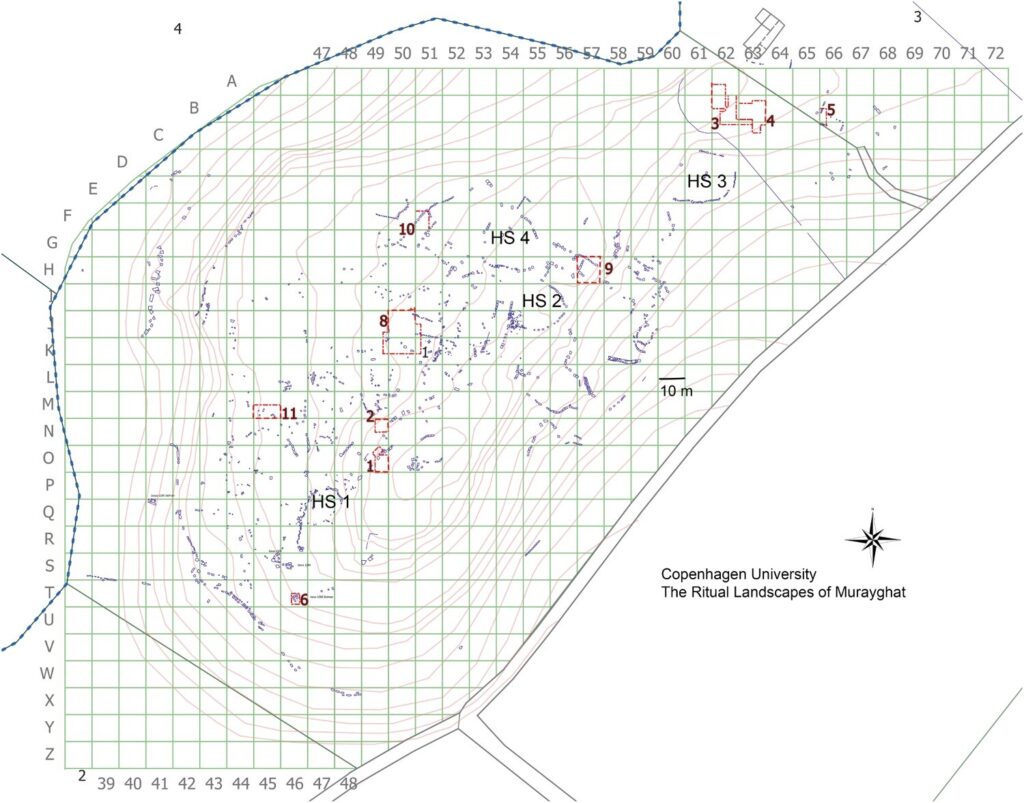

Nestled in the hills southwest of Madaba, Murayghat features a sprawling field of dolmens—stone burial chambers—surrounded by enigmatic standing stones and non-domestic architecture. The research, led by Associate Professor Dr. Susanne Kerner from the University of Copenhagen, suggests that the site may have served as a cultic gathering place during a time of societal upheaval over 5,000 years ago.

Stone Clues to a Disrupted Civilization

The site dates back to the Early Bronze Age IA (around 3600–3300 BCE), a period that followed the decline of the Chalcolithic culture. According to Kerner’s study, the disappearance of copper prestige items, changing climate conditions, and a breakdown of socio-political structures likely triggered a civilizational crisis.

“In a world where temples vanished and the old social order collapsed, people still needed to communicate, organize, and remember,” Kerner writes. “Murayghat may have been one of the places where new forms of identity and belief were forged.”

A Ritual Landscape

Murayghat’s centerpiece is a central knoll flanked by terraced hills, each dotted with collapsed and intact dolmens. These burial structures, some reaching over 4 meters in length, were carefully positioned with sight lines to the knoll and to each other, indicating a coordinated effort in planning.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

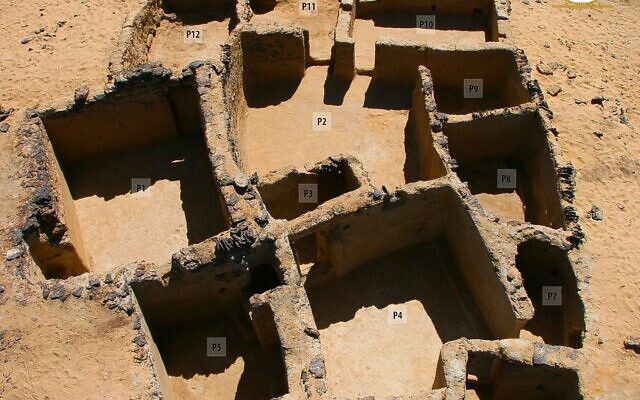

Excavations revealed multiple construction phases and a variety of architectural styles. Lines of orthostats—large upright stone slabs—form partial enclosures, while circular and horseshoe-shaped features suggest communal or ritual use. One striking feature is a large, free-standing monolith known as Hadjar al-Mansub, which stands 2.4 meters tall and faces away from the central site toward the valley—perhaps marking a processional path or ritual axis.

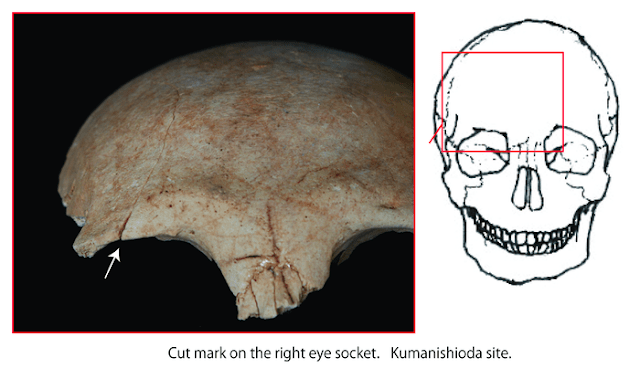

Burial, Feasting, and Memory

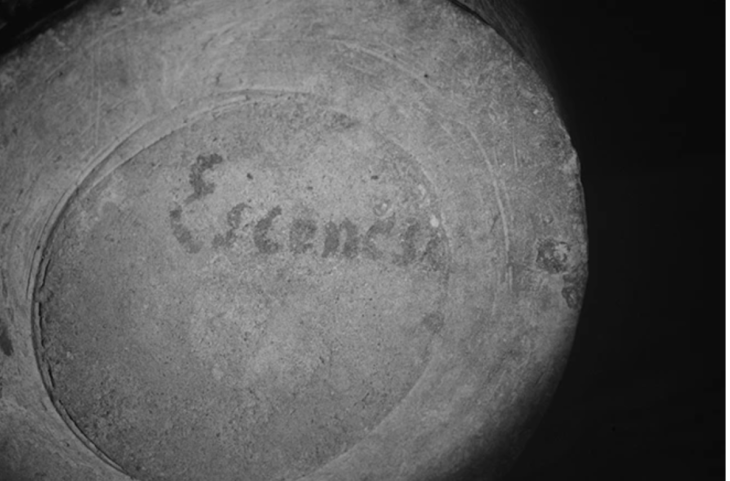

Artifacts found at the site include flint tools, copper objects, horn cores (from goats and gazelles), and unusually large ceramic bowls capable of holding up to 27 liters of food. These “Murayghat bowls” hint at communal feasting rituals—perhaps tied to honoring ancestors or negotiating group identities.

Dolmen fields across the Levant often lie near Early Bronze Age settlements. However, Murayghat lacks clear domestic structures or hearths, reinforcing the theory that this was a special-purpose site. “The architecture is too complex for a residential village,” Kerner asserts. “It’s more plausible that Murayghat functioned as a regional meeting ground—maybe even a sanctuary.”

Reimagining the Bronze Age

Murayghat offers rare insight into how ancient communities responded to crisis. With traditional religious centers in ruins and elite symbols obsolete, people turned to the land—building visible monuments to remember their dead, claim territory, and reconnect with others.

Archaeologists believe Murayghat’s dolmens and standing stones are more than burial markers; they are enduring symbols of a society in transition. The use of local limestone, shaped by hand and placed with intention, speaks to a community trying to make sense of a changing world.

A Site for the Ages

The findings challenge earlier assumptions that dolmen fields were solely nomadic or tribal burial grounds. Instead, they appear to be part of a larger socio-political adaptation—a way for pre-urban societies to stay connected and re-establish order in uncertain times.

As climate shifts and societal stresses mount today, Murayghat reminds us of humanity’s enduring need to adapt, communicate, and commemorate.

The site remains under excavation, but its story—carved in stone—continues to fascinate archaeologists and inspire new questions about the deep roots of belief, memory, and resilience.

Kerner, S. (2025). Dolmens, standing stones and ritual in Murayghat. Levant, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00758914.2025.2513829

Cover Image Credit: View of the central knoll (Area 1) from the north, highlighting multiple alignments of standing stones. Image: The Ritual Landscapes of Murayghat Project / Susanne Kerner