New research finds that Mesopotamians were utilizing hybrids of domesticated donkeys and wild asses to drive their war wagons 4,300 years ago – at least 500 years before horses were bred for the purpose.

Archaeologists excavating in modern-day Syria discovered the full remains of 25 horse-like animals in a stunning burial complex that also held human skeletons and gold, silver, and other precious materials in the early 2000s. The graves, which date back 4,300 years, were discovered in the ancient Mesopotamian city of Umm el-Marra

Many of the equids had been killed, maybe sacrificed, before being buried. Their bones were not like those of horses, donkeys, asses, or other contemporary equids. For years, scientists wondered if these were the remnants of kungas, strong horse-like hybrids highly treasured by the Mesopotamians and recorded in numerous written documents.

The examination of ancient DNA from animal bones discovered in northern Syria answers a long-standing mystery about the “kungas” recorded in ancient records as pulling war wagons.

The equid bones unearthed at Umm el-Marra were hybrids, probably definitely the mythical kungas, according to genetic study, making them the earliest-known hybrids developed by humans. The researchers behind the discovery, which was published (January 14) in Science Advances, also determined which species the Mesopotamians most likely mixed together thousands of years ago to generate kungas, which had previously been unknown.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The new study shows, that kungas were strong, fast, and yet sterile hybrids of a female domestic donkey and a male Syrian wild ass, or hemione — an equid species native to the region.

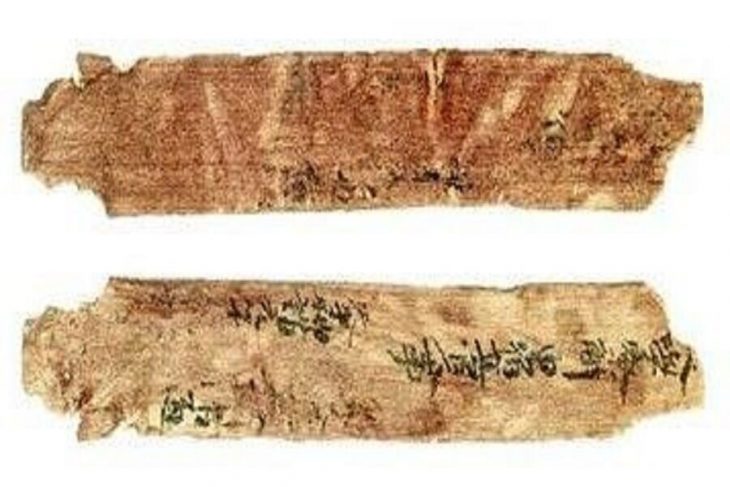

Despite the fact that the best sample from any of the Umm el-Marra equids contained just a tiny fraction of the animal’s original genome, the team was still able to detect thousands of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the DNA. This allowed them to compare the genomes of various equids—including horses, donkeys, and different wild asses such as Persian onagers from Iran, kiangs from Tibet, and khulans from Mongolia—to the Umm el-Marra equids.

The analysis relied on genomes recovered from some of the last-surviving Syrian wild asses and one ancient Syrian wild ass genome from an 11,000-year-old specimen found at the Göbekli Tepe Neolithic archaeological site in modern-day Turkey.

”The Syrian wild ass at the time, prehistoric times, was much larger,” explains study co-author Eva-Maria Geigl. The authors note how their study backs up previous research suggesting that the smaller, more recent Syrian wild asses were likely dwarfed forms, with taller individuals being the norm for this species in ancient times.

Capturing Syrian wild asses would have been extremely difficult for ancient breeders due to their quick, undomesticated nature. “This would explain why these kungas were so expensive and prestigious,” Geigl says.

In ancient texts, kungas are described as costing up to six times as much as a donkey. They were also listed in dowries for royal marriages and were used to pull chariots belonging to members of the elite.

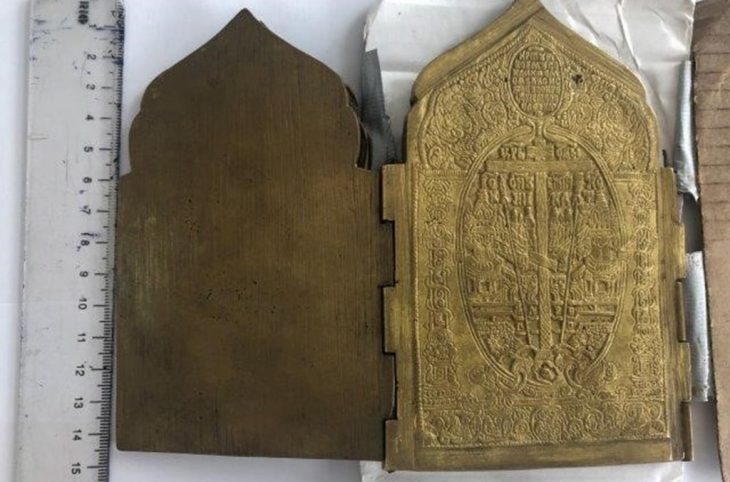

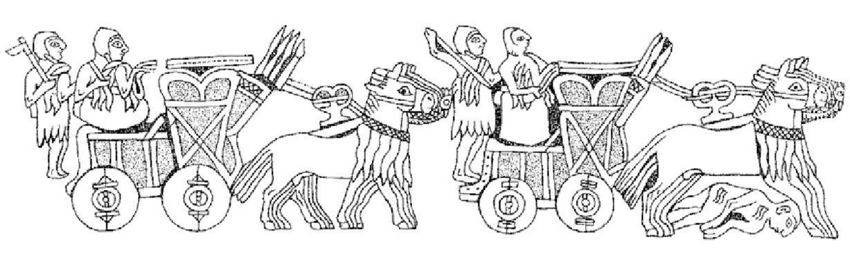

They were prized as war animals, too. A 4,600-year-old artifact called the Standard of Ur, a wooden box found in modern-day Iraq with inlaid depictions of war and peace includes images of kungas pulling battle chariots and trampling enemies in the process.

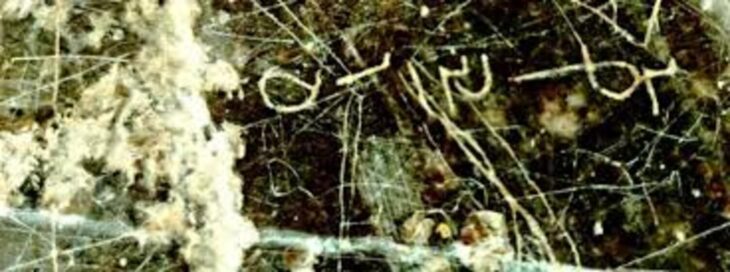

Ancient records show the successor states of the Sumerians — such as the Assyrians — continued to breed and sell kungas for centuries — and a carved stone panel from the Assyrian capital Nineveh, now in the British Museum, shows two men leading a wild ass they had captured.

The kunga bones for the latest study came from a princely burial complex at Tell Umm el-Marra in Northern Syria, which has been dated to around the early Bronze Age between 3000 B.C. and 2000 B.C.; the site is thought to be the ruins of the ancient city of Tuba mentioned in Egyptian inscriptions.