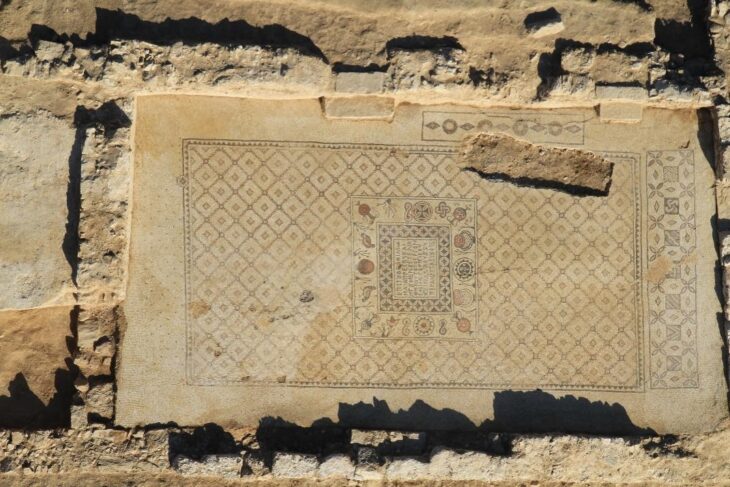

Archaeologists have discovered a shrine containing previously unknown ancient rituals during excavations at Berenike, a Greco-Roman port in Egypt’s eastern desert.

The discovery was made by archaeologists from the Sikait Project led by Professor Joan Oller Guzman at the Autonomous University of Barcelona.

The study, which was recently published in the American Journal of Archaeology, describes the Sikait Project’s excavation of a religious complex from the Late Roman Period.

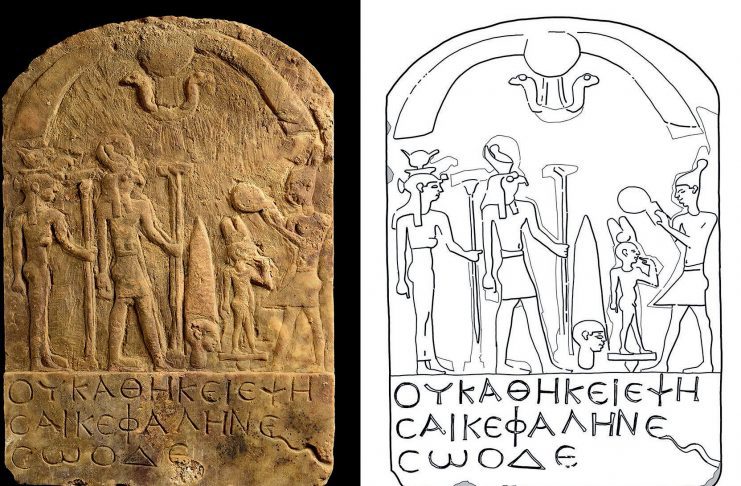

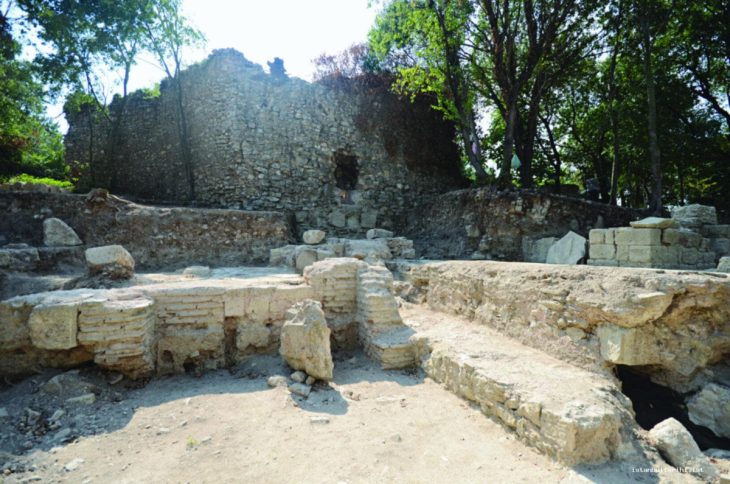

The religious complex, dubbed the “Falcon Shrine” by the researchers, dates from the Late Roman Period, which lasted from the fourth to sixth centuries AD. During this time, the city was partially occupied and controlled by the Blemmyes, as indicated by the discovery of inscriptions on a stele in a small traditional Egyptian temple, which was adapted by the Blemmyes to their own belief system after the 4th century AD.

The Blemmyes were nomadic Eastern Desert people who appeared in written sources between the 7th and 8th centuries BC. The Greek term first appears in a poem by Theocritus and in Eratosthenes in the third century BC. The Blemmyes, according to Eratosthenes, lived with the Megabaroi in the land between the Nile and the Red Sea north of Mero. They had occupied Lower Nubia and established a kingdom by the late 4th century. From inscriptions in the temple of Isis at Philae, a considerable amount is known about the structure of the Blemmyan state.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The most remarkable find in the shrine was around 15 falcons, most of them without their heads. Burial of falcons had already been found in the Nile Valley but this was the first time archaeologists discovered falcons buried within a temple and accompanied by eggs.

This discovery the team considers suggests a new previously unknown ancient ritual when compared to falcon burials in the Nile Valley.

Mummified headless falcons found in other areas were always just individuals, not a group, as in the shrine discovered at Berenike.

The shrine contained the following inscription: “It is improper to boil a head in here” which has been interpreted as a message barring people who enter the shrine from boiling the heads of the animals inside the temple.

“From its archaeological context, the stele almost certainly records an injunction associated with the falcon cult. The text forbade boiling the head of a bird within the area in which the stele was set up,” the researchers wrote in the study.

“All of these elements point to intense ritual activities combining Egyptian traditions with contributions from the Blemmyes, sustained by a theological base possibly related to the worshipping of the god Khonsu (the ancient Egyptian god of the Moon)”, said UAB researcher Professor Joan Oller Guzman.

Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB)

https://doi.org/10.1086/720806

Cover Photo: K. Braulińska; drawing by O.E. Kaper