Rome was not a place that promised a lot for women. Lower-class women were typically public, helping to earn a living for their families. Upper-class women were expected to be more private, but they could also have a lot of political and intellectual power depending on the positions of their relatives. However, it is clear that much of a Roman woman’s life was defined by her male relatives.

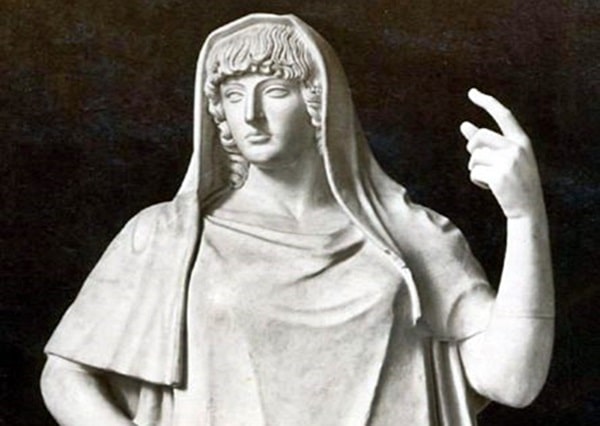

But there was another group in Rome that didn’t have to think about it. These were women who held a sacred duty, from whom girls from noble families were removed from their families for 30 years. These women were expected to spend 30 years of their lives serving the virgin goddess Vesta. They were concerned with the task of perpetuating an eternal flame in Vesta’s temple, and symbolically, with the heart of all Rome.

They have given their families many advantages because of their services, such as individual power and wonderful seats in the Coliseum.

However, if Vestal lets the flame go out, or worse, breaks the vow of chastity, she may face extreme consequences. Her privileged and powerful life is plagued by strict restrictions and high stakes. The fate of Rome itself was in her hands.

How to become a Vestal Virgin?

First of all, you had to be of nobility to be a Vestal Virgin. It was out of the question that one of the lower strata was a Vesta virgin.

Vestal virgins were chosen among daughters of about 6-10 years old. The chief priest, or pontifex maximus, looked for a new Vestal from amongst the most respectable families. In the early days of tradition, girls must be free, and parents’ daughters must also be free. Both parents must be alive, and the girl must have no physical or mental defects.

Later, as fewer families were willing to let their daughter into a restrictive life as nuns, the rules relaxed and the girls of freed slaves became eligible.

After these girls were publicly selected, the young girls would be sent to live in the Atrium Vestae or Vestals House with older nuns who would form their new family for the next thirty years of their lives.

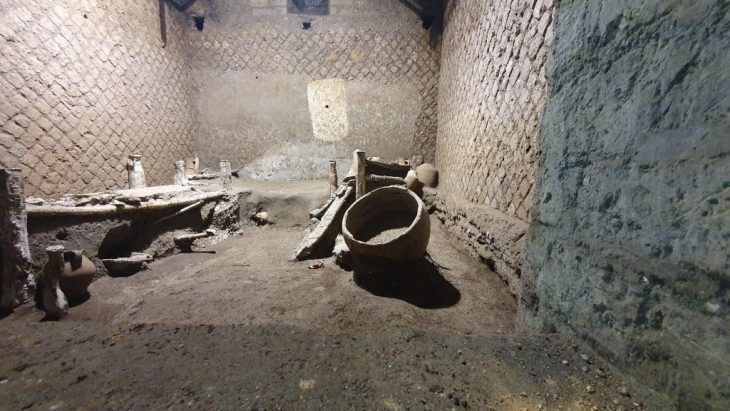

When a Vestal Virgin was chosen, she would join the other nuns at the Temple of Vesta in the Roman Forum. They were expected to perform different tasks such as carrying water from the holy spring and preparing sacred food. But undoubtedly their most important task was to light Vesta’s fire.

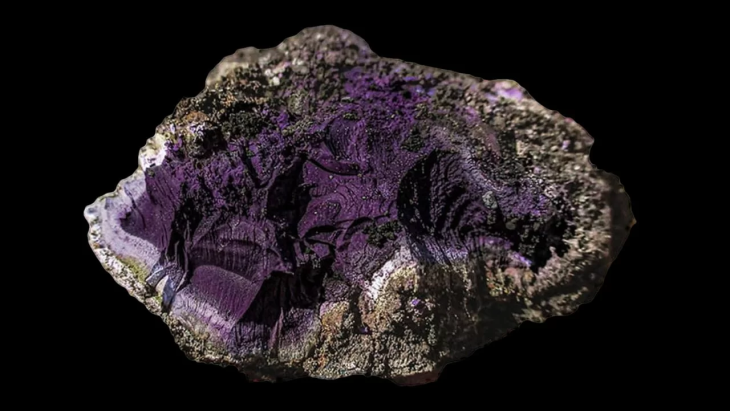

Symbolically, the hearth represented the heart of the home, where the family did their most basic work. The fire burning in the Temple of Vesta represented the house fire for the Roman people. İf on fire it represented stability and strength for all.

In a house, the fire was run by the women of the house. Vestal Virgins, who were unmarried and quasi-independent as opposed to the family’s mother and daughter, were mothers to all of Rome.

İf the Vesta fire goes out?

For a vesta virgin, the burning out of the fire meant that the girl would receive a great punishment when the fire was extinguished, no matter how sacred. Their high status meant that only the high priest, also called the Pontifex Maximus, was allowed to strike them. Their punishment was given in a private place. Curtains were drawn to hide Vestal’s shame.

She says that if the Virgin Vestal is very lucky, she can fix things before anyone finds out and tries to beat her. One day, Aemilia, one of the lucky Vestals, saw that the flame was extinguished and immediately prayed to Vesta. There are many versions of the Aemilia tale. Seeing that the fire was extinguished, the girl throws a piece of cloth on the embers and the fire burns again.

If Vestal virgins break their oaths?

As part of his ministry, Vestal would remain chaste. They were like family members of all Rome – mothers, and sisters of the entire population. Therefore, it was a great betrayal for a Vestal to have a romantic or physical relationship with a Roman.

That particular crime was termed crimen incesti. A confirmed case is rarely found, but when it happened, it caused everyone’s dissatisfaction. The crime was so abhorrent to the Romans that the Vestal Virgins who were found to have violated the celibacy clause suffered a terrible fate.

Vestaller, who was found guilty of this crime, was buried alive. Most scholars agree that this particular punishment was not implemented because no Roman wanted to be directly responsible for the death of the Vestal, although there may be a connection between burying the Vestal alive and the goddess Vesta’s connection to the earth.

Freedom after 30 years

According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the first ten years were devoted solely to learning how to become the best Vestal Virgin possible. The last ten years of a Vestal service had to focus on educating the next group of nuns, while the next ten were devoted to performing rituals.

By 30 years they were free to reenter society and become normal Roman wives. However, although some believe that an old Vestal wedding would bring good fortune, few have been documented to be married.

Being a Vestal Virgin wasn’t too bad!

Being a Vestal wasn’t all that bad, considering the Roman women. While the wives and daughters of Rome were indebted to men who practically dictated their every move in their lives, the Vestals were rare women who were at least responsible for their own destiny.

The Vesta Virgin Virgins formally got rid of the patriarchy that ruled the lives of almost all other women of that era. They have the ability to own their own property, so they can make their own last wishes. Vesta sometimes even appears in court. Because Vestal is considered to have outstanding status and virtue, she can testify without first taking an oath. They are sometimes commissioned to provide important legal documents, such as treaties. In some cases, they can even vote, which is an extremely rare privilege for the male-dominated Roman women.

Source

- Cook, SA (ed.). Cambridge Antik Tarihi. Cambridge University Press, 1971

- Icks, M. The Crimes of Elagabalus. Harvard University Press, 2012

- Gruen, E. (1968). M. ANTONIUS AND THE TRIAL OF THE VESTAL VIRGINS. Rheinisches Museum Für Philologie, 111(1), 59-63. Retrieved February 23, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41244355

- Staples, A. (2013). From Good Goddess to Vestal Virgins: Sex and Category in Roman Religion. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Beard, M. (1980). The Sexual Status of Vestal Virgins. The Journal of Roman Studies, 70, 12-27. doi:10.2307/299553