Twelve severed hands were found in Egypt as part of a horrifying “trophy-taking” practice that was just made revealed by a ground-breaking study.

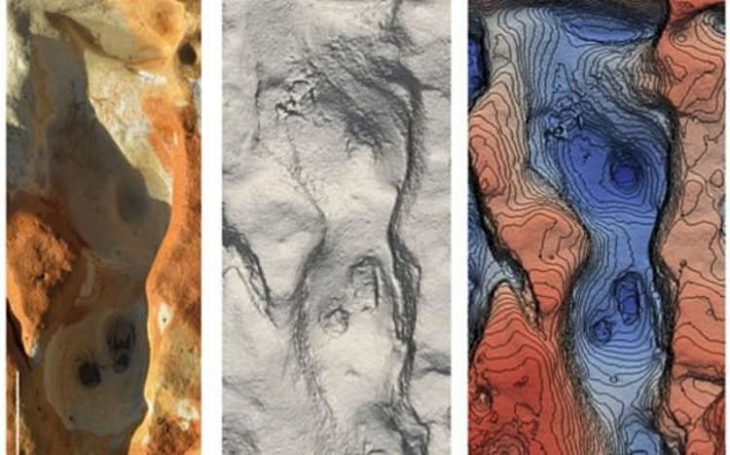

The severed right hands have been discovered in three pits within a courtyard in front of the throne room of a 15th Dynasty (c.1640–1530 BC) Hyksos palace at Avaris/Tell el-Dab‘a in north-eastern Egypt.

This discovery is the first physical evidence of hand amputations in ancient Egypt, shedding new light on the civilization’s dark past.

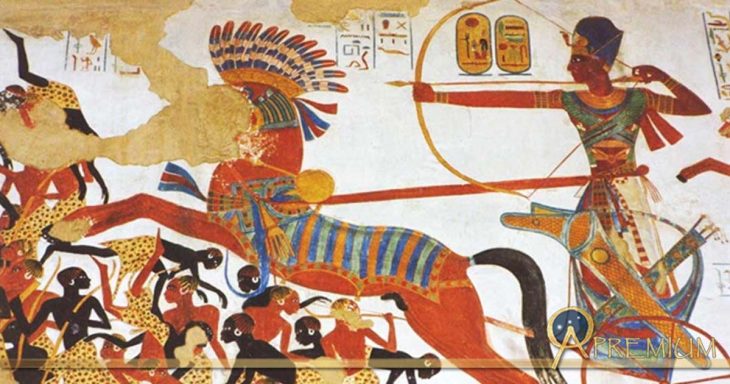

Although the practice of placing severed hands is documented in tomb inscriptions and temple reliefs dating back to the New Kingdom, this is the first instance of an osteological analysis based on physical evidence.

Anatomical markers indicate that the hands belong to at least 12 adults, 11 of whom are male and one of whom is female. Once the attached parts of the forearm were removed, the hands were deposited in the pits with the fingers wide-splayed, primarily on their palm-facing sides.

Only six of the discovered hands have intact proximal row carpal bones, and no signs of cut marks or any soft tissue removal are present. No lower-arm bone fragments were found in the pit, which suggests that these hands were purposefully severed from the lower arms.

The taphonomic and biological analyses of the bones, according to researchers, provide information about the mutilation and preparation of these body parts as well as the individuals to whom they originally belonged.

The custom of severing an enemy’s right hand appears to have been brought to Egypt by the Hyksos, according to researchers, even though the hands cannot be directly linked to a particular ethnic or cultural group. According to a relief depicting a mass of hands at King Ahmose’s temple in Abydos, the Egyptians adopted this practice at the latest during his reign.

Evidence shows that severed hands were prepared and arranged for presentation in a public ceremony in the pharaoh’s palace. “In this politically structured frame, the severed hands served as symbolic currency for status acquisition, within a system of values celebrating warfare and dominance, as argued by other bioarchaeological studies in geographically diverse contexts.

Cutting off the right hand, in particular, would not only have made counting victims easier, but it would also have served the symbolic purpose of removing an enemy’s strength.