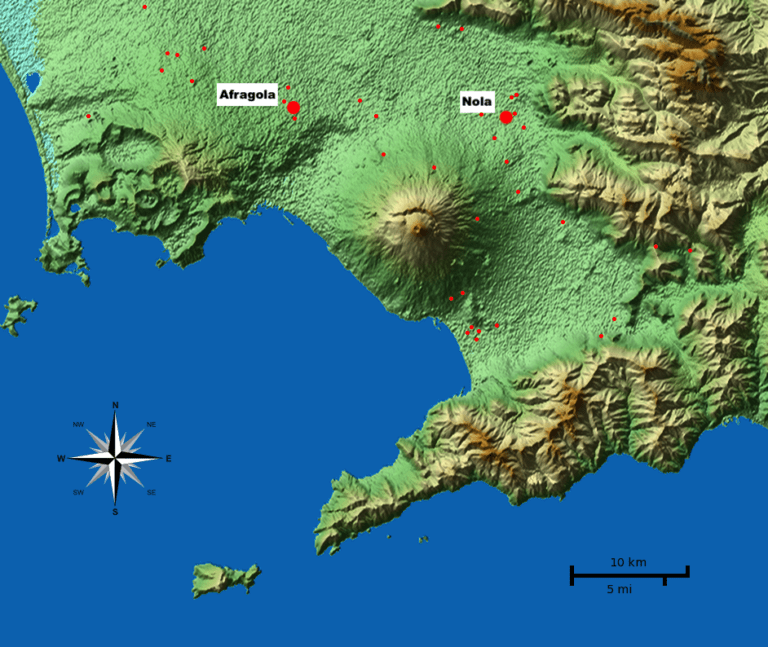

Mount Vesuvius’ Plinian eruption about 4,000 years ago—2,000 years before it buried the Roman city of Pompeii—left remarkable preservation of early Bronze Age village life in the Campania region of southern Italy.

The remarkable preservation of the village of Afragola is unmatched in Europe. It was located near modern Naples, about 10 miles from Mount Vesuvius.

Researchers were curious to see if they could determine the time of year the eruption occurred due to the level of preservation and variety of plants preserved at the site.

Afragola was excavated over an area of 5,000 square meters, making it among one of the most extensively investigated sites of the Early Bronze Age in Italy.

In a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, the researchers explained how the eruption took place in different phases, beginning with a dramatic explosion that primarily transported debris to the northeast.

UConn Department of Anthropology researcher Tiziana Matarazzo said, “The site is exceptional because Afragola was buried by a giant eruption of Vesuvius, and this tells us a lot about the people who lived there and the local habitat. In this case, by finding fruit and agricultural materials, we were able to determine the eruption season, which is not usually possible,”.

Matarazzo added: the last phase brought mainly ash and water – this is the so-called phreatomagmatic phase – which was scattered mainly to the west and northwest, about 25 kilometers from the volcano.

The village was buried in a thick layer of volcanic material during this phase, which replaced the molecules of plant macroremains and produced flawless casts in cinerite (also known as ash tuff), a material that doesn’t degrade for thousands of years.

“Leaves that were in the woods nearby were also covered by mud and ash which was not super-hot, so we have beautiful imprints of the leaves in the cinerite,” said Matarazzo.

The village also had a warehouse where all the grain, various agricultural goods, and fruits were collected from the nearby forests for storage. The building caught fire probably due to the arrival of pyroclastic materials and collapsed, carbonizing the stored vegetal materials inside.

In the Bronze Age, the Campanian Plain was home to a diverse range of food sources, including grains and barley, hazelnuts, acorns, wild apples, dogwood, pomegranates, and cornelian cherries, all of which were exceptionally well-preserved in the aftermath of the volcanic eruption.

“This eruption was so extraordinary that it changed the climate for many years afterward. The column of the Plinian eruption rose to basically the flight altitude of airplanes. It was unbelievable. The cover of ash was so deep that it left the site untouched for 4,000 years. Now we get to learn about the people who lived there and tell their stories,” said Matarazzo.

The evidence points toward the eruption happening in the fall, as the villagers amassed their food stores from the nearby woods.