A multidisciplinary research team has resolved a long-standing chronological puzzle surrounding one of Europe’s rarest archaeological discoveries: the so-called “Princess of Bagicz,” the only well-preserved wooden log coffin from the Roman Iron Age found in Poland.

Published in Archaeometry and led by Dr. Marta Chmiel-Chrzanowska, the study applied dendrochronology—tree-ring dating—to address a nearly century-wide discrepancy between traditional typological analysis and radiocarbon testing. The findings not only establish a firm date for the burial but also demonstrate how environmental and dietary factors can significantly distort radiocarbon results.

Discovery on an Eroding Baltic Coast

The burial was uncovered in 1898 near Bagicz on Poland’s Baltic coast, when coastal erosion caused a section of cliff to collapse. In this region, the shoreline can retreat by up to a meter per year, gradually revealing archaeological remains that had long been sealed beneath the soil.

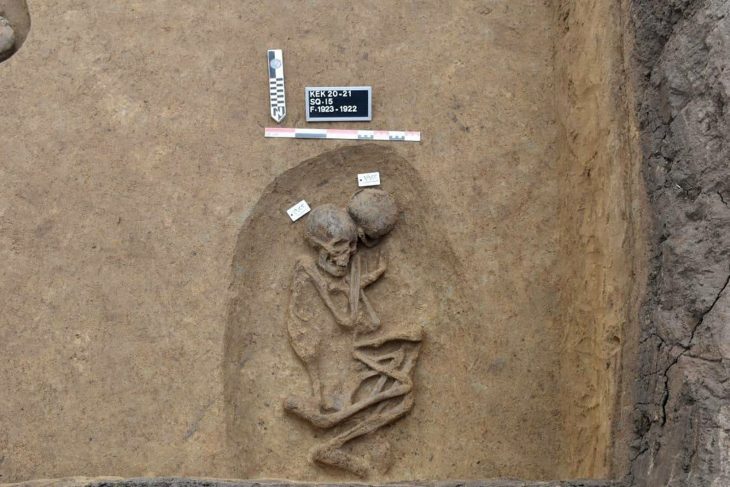

The coffin has been linked to the Wielbark culture, which flourished between the 1st and 4th centuries CE. Communities associated with this culture commonly interred their dead in hollowed-out log coffins or graves lined with organic materials such as twigs. However, wooden structures rarely survive in the acidic soils of Pomerania, making the Bagicz coffin an exceptional find and the only well-preserved example of its kind from the region.

Inside the oak log coffin lay the remains of a young woman accompanied by several ornaments, including a bronze fibula, a decorative pin, two bronze bracelets, and a necklace composed of glass and amber beads. Early documentation also mentioned a small wooden stool and a cattle hide, though these organic materials did not survive long enough to be incorporated into the collections of the National Museum in Szczecin.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Because the burial initially appeared isolated and contained ornamental objects, early researchers interpreted the woman as a person of elevated social status, leading to the enduring nickname “Princess of Bagicz.” Subsequent excavations, however, revealed a nearby cemetery, indicating that she had been part of a larger burial ground and suggesting that her social standing may not have been as exceptional as once believed.

A 100-Year Dating Discrepancy

Establishing the burial’s age proved unexpectedly complex. In the 1980s, archaeologists conducted a typological analysis of the grave goods, particularly the bronze ornaments, and concluded that the burial most likely dated to the mid-2nd century CE, approximately between 110/120 and 160 CE. This conclusion aligned with known stylistic patterns from Roman-period Central Europe.

Decades later, in 2018, radiocarbon analysis of one of the woman’s teeth produced a dramatically earlier date, placing the burial between 113 BCE and 65 CE with high probability. The nearly 100-year discrepancy between the two methods raised serious questions about which chronology was reliable.

Dendrochronology Provides the Decisive Evidence

To resolve the conflict, researchers turned to dendrochronology in 2024. By analyzing the growth rings of the oak used to construct the coffin and comparing them with established regional tree-ring chronologies, they determined that the tree had been felled around 120 CE, with a margin of error of plus or minus seven to eight years.

This result closely matches the earlier typological assessment and clearly indicates that the radiocarbon date was artificially older than the actual burial.

Why the Radiocarbon Date Appeared Too Old

The research team investigated why radiocarbon analysis had produced an earlier date. Stable isotope analysis revealed that the woman consumed a substantial amount of animal protein and likely freshwater fish. Fish inhabiting rivers and lakes can absorb dissolved ancient carbon from limestone or glacial deposits. When humans consume such fish, their skeletal remains may incorporate that older carbon, creating what is known as a reservoir effect. This phenomenon can make individuals appear significantly older in radiocarbon tests than they truly are.

The environmental context may have compounded the issue. Studies indicate that the region’s water was moderately hard, meaning it contained elevated levels of dissolved carbonates. Aquatic organisms living in such environments can incorporate ancient carbon, which then enters the human food chain and distorts radiocarbon measurements.

Strontium isotope analysis further complicated the picture by suggesting that the woman’s isotopic values resemble those recorded in parts of Scandinavia, including Öland. However, glacial geological processes in Pomerania produce strontium signatures similar to those in Scandinavia, making it difficult to determine whether she was a migrant or a local inhabitant. At present, there is no definitive evidence confirming migration.

What This Discovery Reveals About Dating the Past

The redating of the Princess of Bagicz burial carries broader implications for archaeological research. The case demonstrates that even widely trusted scientific techniques such as radiocarbon dating can produce misleading results when environmental and dietary factors are not fully accounted for. It highlights the exceptional precision of dendrochronology when preserved timber is available and shows how combining multiple analytical methods can produce a far more reliable historical framework than relying on a single approach.

By integrating artifact typology, radiocarbon analysis, stable isotope research, strontium data, and tree-ring dating, the researchers were able to establish a secure chronology for the burial. The oak coffin, felled around 120 CE, anchors the woman firmly in the early 2nd century Roman Iron Age.

More than a century after coastal erosion first exposed the log coffin near Bagicz, scientific advances have finally resolved its dating controversy. While the woman buried within may no longer be considered a princess, her grave has become an important case study in archaeological methodology, illustrating how tree rings can decisively clarify debates that radiocarbon evidence alone cannot settle.

Chmiel-Chrzanowska, M., Fetner, R., & Krąpiec, M. (2026). Unrevealing the date of a Roman Iron Age period burial in log coffin from Bagicz: A multidisciplinary approach. Archaeometry, (arcm.70113). doi:10.1111/arcm.70113

Cover Image Credit: Contemporary view of the Princess of Bagicz’s oak log coffin exhibited in Poland. Chmiel-Chrzanowska et al., Archaeometry (2026).