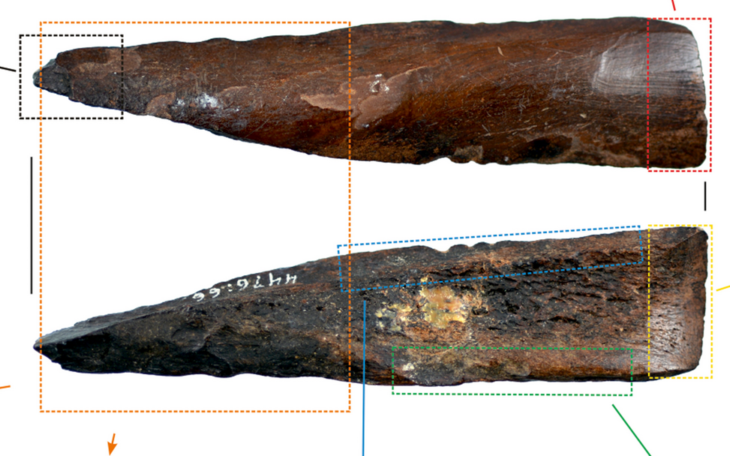

Researchers in Kent in southeastern England have discovered a prehistoric handaxe so big it would have been almost impossible to wield as a cutting tool. The handaxe is the third largest ever found in Britain.

Excavations also uncovered artifacts preserved in deep Ice Age sediments on a hillside above the Medway Valley. A total of 800 artifacts were discovered, thought to be more than 300,000 years old and buried in material that filled a sinkhole and an ancient river channel.

The researchers, from UCL Archaeology South-East, unearthed several handaxes, and two of them were giants of a form known as a ficron, characterized by a rounded thick base tapering to a long, finely-worked tip.

One is 22 cm (nine inches) long but missing its tip. The other is 29.5 cm (11.6 inches) long and intact. It is 11.3 cm (4.4 inches) wide at its widest point.

Letty Ingrey, of UCL Institute of Archaeology, said: “We describe these tools as giants when they are over 22cm long, and we have two in this size range.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

“The biggest, a colossal 29.5cm in length, is one of the longest ever found in Britain. These hand axes are so big it’s difficult to imagine how they could have been easily held and used. While right now, we aren’t sure why such large tools were being made, or which species of early human were making them, this site offers a chance to answer these exciting questions.”

The site is thought to date to a period in the early prehistory of Britain when Neanderthal people and their cultures were beginning to emerge and may even have shared the landscape with other early human species.

While archaeological finds of this age, including another spectacular ‘giant’ handaxe, have previously been discovered in the Medway Valley, this is the first time they have been discovered as part of a large-scale excavation, providing new insights into the lives of their makers.

Amongst the unearthed artifacts were two extremely large flint knives described as “giant handaxes”. Handaxes are stone artifacts that have been chipped, or “knapped,” on both sides to produce a symmetrical shape with a long cutting edge.

Dr Matt Pope (UCL Institute of Archaeology), said: “The excavations at the Maritime Academy have given us an incredibly valuable opportunity to study how an entire Ice Age landscape developed over a quarter of a million years ago. A programme of scientific analysis, involving specialists from UCL and other UK institutions, will now help us to understand why the site was important to ancient people and how the stone artifacts, including the ‘giant handaxes’ helped them adapt to the challenges of Ice Age environments.”

The research team is now working on identifying and studying the recovered artifacts to better understand who created them and what they were used for.

Cover Photo: ASE Senior Archaeologist Letty Ingrey inspects the largest handaxe. UCL Institute of Archaeology