According to a new study, modern languages ranging from Japanese and Korean to Turkish and Mongolian may have had a common origin from ancient China some 9,000 years ago.

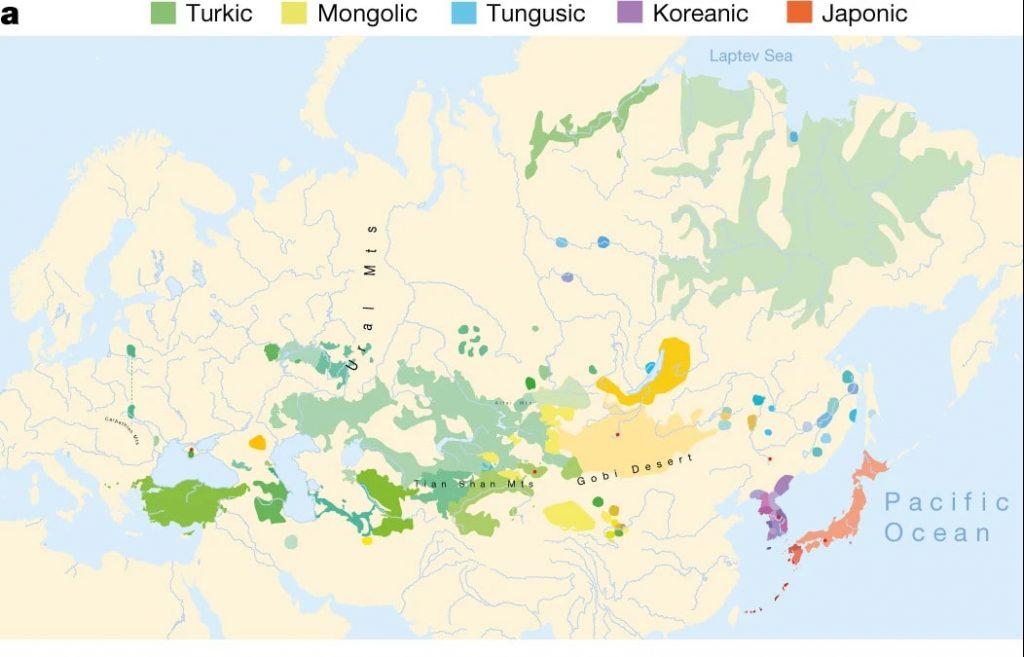

The findings detailed on Wednesday show that hundreds of millions of individuals who speak what the researchers term Trans Eurasian languages spanning a 5,000-mile span share a common genetic ancestor (8,000 km).

An international team of scientists has concluded that the Trans-Eurasian languages, also known as Altai, can be traced back to early millet growers in the Liao Valley in what is now Northeast China and that its spread was driven by agriculture.

The findings show how humankind’s adoption of agriculture after the Ice Age fueled the spread of some of the world’s main language groups. As hunter-gatherers converted to an agricultural existence, millet was an important early crop.

The origins and degree to which the five groups that make up the Transeurasian family are related have long been an area of contention among scholars.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

There are 98 Trans Eurasian languages. Numerous Turkic languages, such as Turkish in portions of Europe, Anatolia, Central Asia, and Siberia, as well as various Mongolic languages, such as Mongolian in Central and Northeast Asia, and various Tungusic languages in Manchuria and Siberia, are among them.

Based on genetic and archaeological evidence, as well as linguistic analysis, the researchers concluded that the languages spread north and west into Siberia and the steppes, and east into Korea and Japan as farmers moved across northeast Asia — a conclusion that challenges the traditional “pastoralist hypothesis,” which proposed that nomads led the dispersal away from the eastern steppe.

The research underscored the complex beginnings of modern populations and cultures.

“Accepting that the roots of one’s language, culture or people lie beyond the present national boundaries is a kind of surrender of identity, which some people are not yet prepared to make,” said comparative linguist Martine Robbeets, leader of the Archaeolinguistic Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany and lead author.

“But the science of human history shows us that the history of all languages, cultures, and peoples is one of extended interaction and mixture,” he added.

The researchers devised a dataset of vocabulary concepts for the 98 languages, identified a core of inherited words related to agriculture, and fashioned a language family tree.

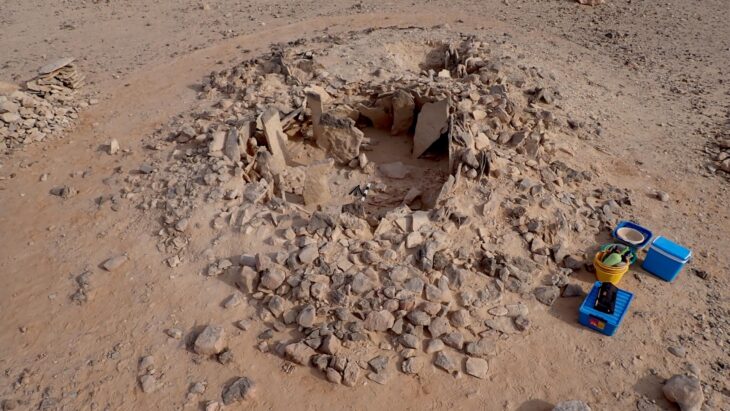

Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History archaeologist and study co-author Mark Hudson, the researchers compared artifacts from 255 archaeological sites in China, Japan, the Korean peninsula, and the Russian Far East, looking for similarities in pottery, stone tools, and plant and animal remains. They also took into account the dates of 269 old agricultural remnants found at various locations.

Farmers in northeastern China ultimately supplemented millet with rice and wheat, an agricultural package that was passed down when these communities went to the Korean peninsula about 1300 BC and then to Japan around 1000 BC, according to the study.

For example, a woman’s remains found in Yokchido in South Korea had 95 percent ancestry from Japan’s ancient Jomon people, indicating her recent ancestors had migrated over the sea.

“By advancing new evidence from ancient DNA, our research thus confirms recent findings that Japanese and Korean populations have West Liao River ancestry, whereas it contradicts previous claims that there is no genetic correlate of the Transeurasian language family,” the researchers said.

The researchers from Britain, China, the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, Russia, the Netherlands and the United States published their findings in the journal Nature on Wednesday.