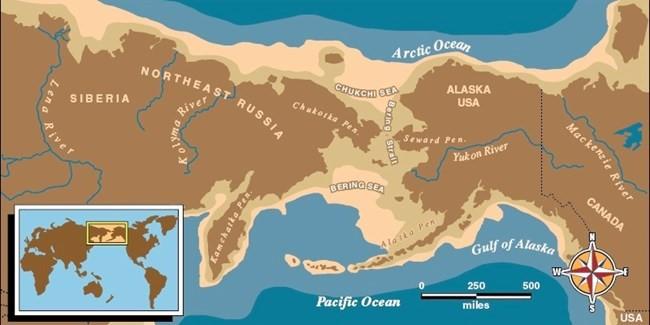

A new study shows that the Bering Land Bridge, the strip of land that once connected Asia to Alaska, emerged far later during the last ice age than previously thought.

Princeton scientists found that the Bering Land Bridge was flooded until 35,700 years ago, with its full emergence occurring only shortly before the migration of humans into the Americas.

The unexpected findings shorten the window of time that humans could have first migrated from Asia to the Americas across the Bering Land Bridge.

The study was published on December 27 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The findings also indicate that there may be a less direct relationship between climate and global ice volume than scientists had thought, casting into doubt some explanations for the chain of events that causes ice age cycles.

“This result came totally out of left field,” said Jesse Farmer, postdoctoral researcher at Princeton University and co-lead author on the study. “As it turns out, our research into sediments from the bottom of the Arctic Ocean told us not only about past climate change but also one of the great migrations in human history.”

Insight into ice age cycles

During the periodic ice ages over Earth’s history, global sea levels drop as more and more of Earth’s water becomes locked up in massive ice sheets. At the end of each ice age, as temperatures increase, ice sheets melt and sea levels rise. These ice age cycles repeat throughout the last 3 million years of Earth’s history, but their causes have been hard to pin down.

By reconstructing the history of the Arctic Ocean over the last 50,000 years, the researchers revealed that the growth of the ice sheets — and the resulting drop in sea level — occurred surprisingly quickly and much later in the last glacial cycle than previous studies had suggested.

“One implication is that ice sheets can change more rapidly than previously thought,” Farmer said.

During the last ice age’s peak of the last ice age, known as the Last Glacial Maximum, the low sea levels exposed a vast land area that extended between Siberia and Alaska known as Beringia, which included the Bering Land Bridge. In its place today is a passage of water known as the Bering Strait, which connects the Pacific and Arctic Oceans.

Based on records of estimated global temperature and sea level, scientists thought the Bering Land Bridge emerged around 70,000 years ago, long before the Last Glacial Maximum.

But the new data show that sea levels became low enough for the land bridge to appear only 35,700 years ago. This finding was particularly surprising because global temperatures were relatively stable at the time of the fall in sea level, raising questions about the correlation between temperature, sea level and ice volume.

“Remarkably, the data suggest that the ice sheets can change in response to more than just global climate,” Farmer said. For example, the change in ice volume may have been the direct result of changes in the intensity of sunlight that struck the ice surface over the summer.

“These findings appear to poke a hole in our current understanding of how past ice sheets interacted with the rest of the climate system, including the greenhouse effect,” said Daniel Sigman, Dusenbury Professor of Geological and Geophysical Sciences at Princeton University and Farmer’s postdoctoral advisor. “Our next goal is to extend this record further back in time to see if the same tendencies apply to other major ice sheet changes. The scientific community will be hungry for confirmation.”

New context for human migration

The timing of human migration into North America from Asia remains unresolved, but genetic studies tell us that ancestral Native American populations diverged from Asian populations about 36,000 years ago, the same time that Farmer and colleagues found that the Bering Land Bridge emerged.

“It’s generally believed that the land bridge was open for a while, and then humans crossed it at some point,” Sigman said. “But our new data suggest that the land bridge was not open, and as soon as it opened up, human populations made their way into North America.”

The finding raises questions about why humans decided to migrate as soon as the land bridge opened, and how humans made their way across the land bridge with no previous knowledge of the landscape.

The researchers noted that they need to be cautious when considering these implications, as the interpretation requires combining very different types of information, including the new data and the information of human geneticists and paleoanthropologists. They look forward to seeing how their results are built upon by these other scientific communities.

A window to the past

To reconstruct the history of the Bering Strait, Farmer and Sigman sought an ocean chemical fingerprint.

Pacific waters carry high concentrations of nitrogen molecules that have a distinct chemical composition, known as an isotope ratio. Today, waters from the Pacific Ocean travel northwards across the Bering Strait into the Arctic Ocean, carrying a traceable nitrogen isotope ratio.

By measuring nitrogen isotopes in sediments at the bottom of the Arctic Ocean, Farmer found that the fingerprint of Pacific Ocean nitrogen disappeared when the Bering Strait was closed during the peak of the last ice age, as expected.

But when Farmer continued his analyses further back in time – to about 50,000 years ago – he found that the Pacific nitrogen fingerprint returned far more recently than researchers had thought possible.

“When Jesse showed me his data, he didn’t need to explain to me what had happened,” Sigman said. “It was too large of a change to be anything other than a previous opening of the Bering Strait.”

To understand the implications for global sea level, Farmer and Sigman collaborated with Tamara Pico, a sea level expert and professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at UC Santa Cruz, Princeton undergraduate Class of 2014, and co-lead author on the paper. Pico compared Farmer’s results with sea level models based on different scenarios for the growth of the ice sheets.

“When Jesse contacted me I was so excited,” Pico said. “A large part of my PhD thesis was focused on how fast global ice sheets grew leading into the Last Glacial Maximum, and much of my work suggests that they might have grown faster than previously thought.”

Farmer’s nitrogen analyses provided a new set of evidence to back up Pico’s research about sea levels during the last ice age.

“The exciting thing to me is that this provides a completely independent constraint on global sea level during this time period,” Pico said. “Some of the ice sheet histories that have been proposed differ by quite a lot, and we were able to look at what the predicted sea level would be at the Bering Strait and see which ones are consistent with the nitrogen data.”

“This study brought together experts in the Arctic Ocean, nitrogen cycling, and global sea level. And the outcome has consequences not only for climate and sea level but also for human prehistory,” Farmer said. “One of the thrilling aspects of paleoclimate research is the opportunity to collaborate across such a broad range of subjects.”

Cover Photo: Cape Espenberg, the northern tip of the Seward Peninsula, Bering Land Bridge National Preserve, western Alaska, U.S. Photo: Michael J. Thompson/U.S. National Park Service