On South Korea’s western shoreline, where vast UNESCO-listed tidal flats stretch toward the horizon, an unusual archaeological mystery has captured public imagination. Earlier this month, South Korean researchers revealed a newly recovered Goryeo-era celadon cargo—87 bowls and cups dating to the mid-12th century—that appear so pristine that many observers questioned whether they could really be nearly 900 years old.

The pieces were lifted from waters off Taean, not far from where a 15th-century Joseon tax vessel known as Mado 4 was also excavated this season. Photographs released by the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage (NRIMCH) showed the celadon placed on black fabric and acrylic stands, their surfaces shining as though they had come straight from a kiln rather than the seabed.

But to underwater archaeologists, the real story is not about mystery—it is about the remarkable preservation power of the West Sea’s clay-rich mudflats.

Why Did the 12th-Century Ceramics Survive in Perfect Condition?

What shocked the public was not only the celadon’s luster but also its astonishing completeness.

“In this case, we recovered all 87 celadon pieces intact,” said Hong Gwang-hui, a researcher with NRIMCH’s Underwater Excavation Division. “The preservation rate was effectively 100 percent.”

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

The team found the cargo in tightly nested stacks—almost certainly the same packing configuration used when the vessel first set sail in the 12th century. This arrangement, Hong explained, acts as a natural buffer. The outer bowls shield the inner pieces, distributing external impact and preventing significant breakage.

Even minor cracks, if they formed at all, were easily restorable. Because all pieces emerged whole, the institute did not need to “select” the best ones for press photographs. What the public saw is essentially the full assemblage, untouched aside from basic cleaning.

The Hidden Power of Tidal Flats: A Natural Preservation Chamber

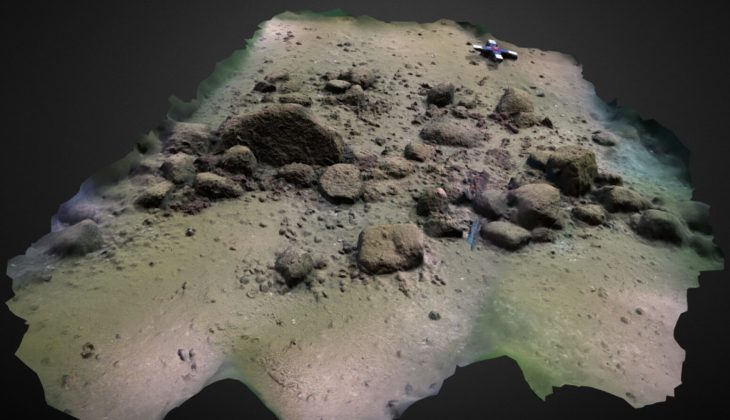

Understanding why the celadon looks new requires understanding where it rested for nearly a millennium. Korea’s west coast is lined with broad tidal flats—one of the world’s richest mudflat systems—recognized by UNESCO for their ecological value. Their significance for maritime archaeology, however, is equally profound.

“Our west coast tidal flats are dominated by dense clayey deposits,” explained Park Ye-ri, also a researcher at NRIMCH. “Once a wreck settles and is buried, the artifacts are essentially sealed under a thick mud layer.”

That mud layer produces two essential preservation effects.

First, it creates a low-oxygen environment that suppresses microbial activity. This dramatically slows the degradation of organic materials such as wood, seeds, rope, bamboo tallies or cargo tags—objects that typically decay rapidly underwater.

Second, clay immobilizes whatever it buries. Unlike sand or rock, where waves and currents can jostle artifacts, cohesive mud holds objects firmly in place. There is no rolling, scraping or abrasion—three of the greatest threats to underwater ceramics.

“Once a bowl sinks into cohesive mud, it doesn’t move,” Park said. “It doesn’t scrape against rocks. That’s why it survives.”

Why Shipwrecks Elsewhere in Korea Look Very Different

The nearly mint-condition Taean celadon is not representative of all Korean shipwrecks. Move south toward Jeju Island or across rocky coastal shelves, and the preservation picture changes dramatically.

For years, NRIMCH has excavated a Chinese Southern Song–era trading ship off Sinchang-ri on Jeju’s coast. Unlike the clay of Taean, the seabed there consists mostly of rock and sand, and is exposed to powerful wave action.

“There the seabed is mostly rock and sand,” Park explained. “The area is exposed to strong wave energy, and there is a higher possibility of damage from microorganisms and marine life.”

Ceramics from this site frequently show heavy breakage, erosion and thick accretions. Many survive only as fragments. The contrast underscores that Taean’s exceptional results are environmental rather than miraculous.

Similar mudflat conditions exist elsewhere in East Asia, including across the Yellow Sea in China. Hong notes that shipwrecks such as the famous Nanhai One also demonstrate exceptional preservation thanks to similarly dense sediment.

What makes Taean distinctive is the convergence of factors: shallow coastal waters, extensive mudflats and centuries of heavy state and commercial traffic, all creating a dense cluster of well-preserved wreck sites.

Why This Celadon Find Matters — and What Comes Next

While the celadon bundles have captivated the public, specialists emphasize that the broader archaeological value will depend on what the excavation uncovers next.

“Simply finding a stack of celadon is not, by itself, extraordinary,” Hong noted. “We have many examples of large ceramic cargoes from Korean waters.”

Divers have already recovered promising contextual material near the site, including a wooden anchor, anchor stones, rice grains and timber fragments. These clues suggest the presence of a previously unknown Goryeo-era ship, now informally labeled “Mado 5,” likely buried beneath the mud.

The most valuable discoveries, however, would be written evidence—wooden tags or bamboo tallies traditionally tied to ceramic cargoes during the Goryeo and Joseon periods. Such inscriptions can reveal kiln origins, shipping destinations, owners and tax records, allowing archaeologists to reconstruct trade networks and administrative systems.

“Providing that kind of context is what archaeology aims to do,” Hong said. “We are not just raising artifacts; we are reconstructing the connections around them.”

For now, the pristine celadon bowls of Taean stand as a striking reminder that the past sometimes survives not by chance, but thanks to the quiet work of mud, time and a remarkably protective seabed.

Cover Image Credit: Divers from the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage inspect a tightly stacked bundle of celadon bowls on the seabed off Taean, a West Sea coast renowned for its expansive tidal mudflats and historic maritime corridors. Yonhap News Agency.