Archaeology often surprises us with unexpected finds, but few discoveries capture the imagination like the recent unearthing of a simple clay vase in the Sharjah desert of the United Arab Emirates. What at first looked like an ordinary vessel turned out to be a treasure trove of 409 silver coins dating back more than 2,300 years. Linked to the legacy of Alexander the Great and the Hellenistic period, this extraordinary find reshapes our understanding of Arabia’s role in ancient global trade networks.

A Vase That Weighed Too Much

In 2021, archaeologists excavating at the ancient city of Mleiha discovered a clay vase that seemed unusually heavy, weighing more than 9 kilograms. When they carefully opened it, they found not water or grain but a stunning collection of silver coins—tetradrachmas from the 3rd century BC.

These coins were not only symbols of wealth but also powerful cultural artifacts that reflected the fusion of Greek influence with Arabian identity.

Coins Bearing the Mark of Alexander the Great

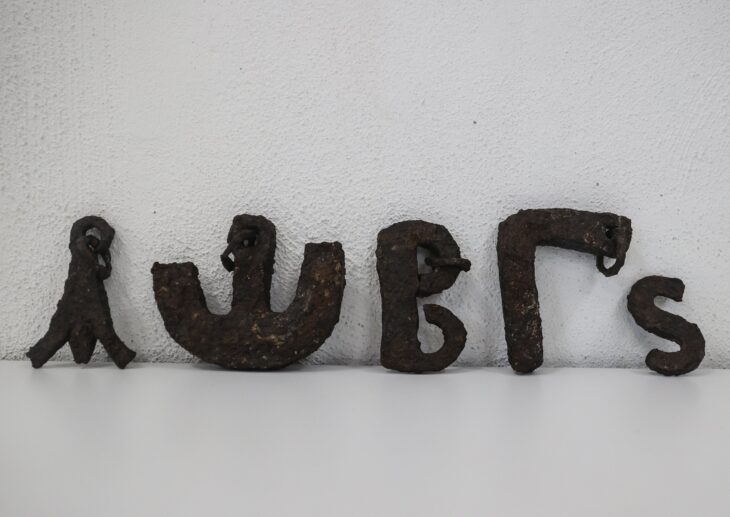

Most of the coins in the hoard are tetradrachmas, each weighing between 16 and 17 grams. The earliest examples depict Alexander the Great represented as Hercules, wearing the lion skin headdress, on one side, and Zeus seated on his throne on the other. These images illustrate the enduring power of Alexander’s iconography long after his empire fragmented.

Over time, the designs evolved. Later coins carried Aramaic inscriptions and local motifs, signaling a cultural transformation. Arabia was not merely imitating Greek designs but adapting them, creating a hybrid identity that combined international symbols of power with local traditions. This evolution reflects how Arab communities engaged with, reinterpreted, and reshaped external influences.

📣 Our WhatsApp channel is now LIVE! Stay up-to-date with the latest news and updates, just click here to follow us on WhatsApp and never miss a thing!!

Mleiha: A Hub of Trade and Culture

The discovery underscores the strategic importance of Mleiha. Situated between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, Mleiha was more than a farming settlement—it was a vibrant hub on trade routes that linked India with the Mediterranean world. Merchants passing through exchanged spices, incense, textiles, and precious metals, requiring a currency that could be recognized across borders. The silver coins found in the vase demonstrate that Arabia’s merchants produced money inspired by Greek prototypes yet tailored to their own economic needs.

Evidence from excavations reveals that Mleiha was far from isolated. Similar Hellenistic-inspired coins have been found across the Gulf, including in Bahrain and Kuwait. This points to the existence of a regional monetary network, suggesting that Arabia was already embedded in a complex web of international commerce.

More Than Just Money: A Cultural Snapshot

The Mleiha coin hoard offers more than economic insight—it provides a window into cultural exchange. The combination of Greek symbols and Aramaic inscriptions illustrates how Arabia was a crossroads of civilizations. These coins show how societies negotiated identity and power, blending outside influences with local traditions to craft unique cultural expressions.

The vase itself becomes a metaphor: a humble container hiding a wealth of information. Just as the coins reveal evolving political and economic realities, the discovery illustrates how Arabia was deeply connected to the broader ancient world.

The Broader Context of Mleiha

Archaeological evidence shows that Mleiha’s history extends far beyond the Hellenistic period. Human activity in the region dates back as early as 130,000 years ago. In later centuries, the settlement thrived due to advanced underground irrigation systems, known as falaj, which allowed agriculture to flourish in the desert. By the time the coin hoard was hidden, Mleiha had grown into a fortified city with palaces, temples, and workshops.

This urban complexity helps explain why such a treasure was accumulated and concealed. The coins were not only valuable currency but also potent symbols of prestige and power.

Rewriting the Map of Ancient Trade

The implications of the discovery are profound. Until recently, many historians believed that Hellenistic influence was limited to regions around the Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, and northern India. The Mleiha coin hoard demonstrates that the Arabian Peninsula was not only influenced by these networks but was an active participant in them.

The transition from Greek iconography to localized designs also reveals that Arabia was not a passive receiver of culture. Instead, it actively redefined imported ideas, using them as tools for economic exchange, political authority, and cultural expression.

Conclusion: A Treasure That Changes History

The 2,300-year-old silver coin hoard found in Mleiha is far more than a remarkable archaeological discovery—it is a story of connection, exchange, and identity. These coins embody the intersection of cultures, economies, and empires, proving that Arabia played a far more significant role in the ancient world than previously imagined.

From Alexander the Great’s iconic imagery to inscriptions in local languages, the coins chart the region’s transformation. They remind us that even in antiquity, Arabia was a key player in global networks—a desert crossroads where East met West and where cultural fusion thrived.

Sharjah Archaeology Authority (SAA)

Cover Image Credit: Sharjah Archaeology Authority (SAA)