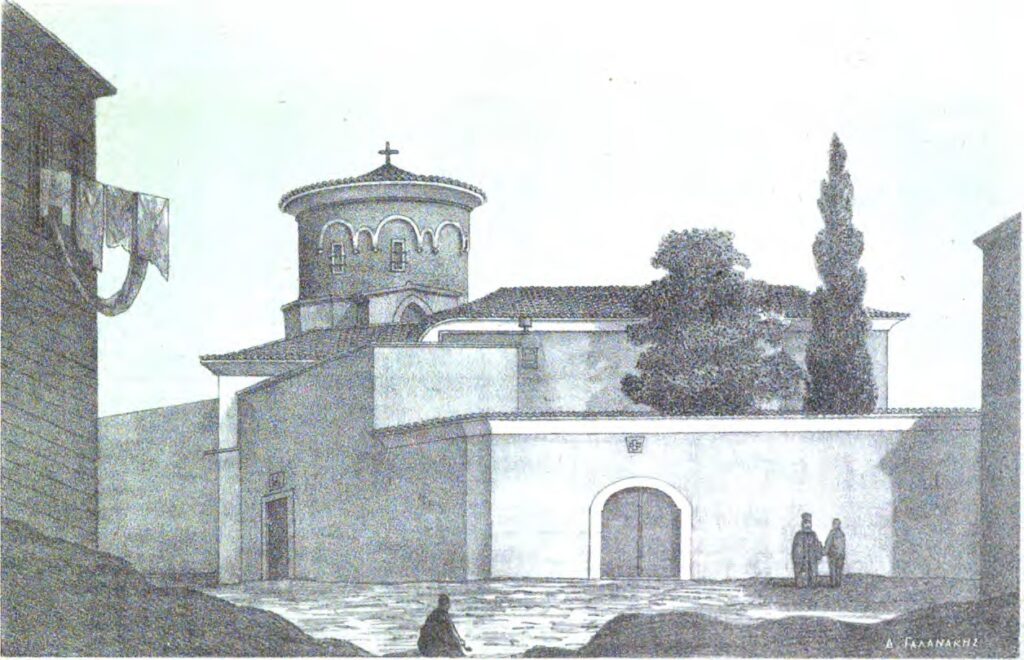

Nestled at the base of the imposing Phanar Greek Orthodox College, a landmark intrinsically linked to the panoramic vistas of Istanbul’s Golden Horn, lies a modest church that has silently borne witness to a captivating tapestry of history. The Church of St. Mary of the Mongols, affectionately known as the “Kanlı Kilise” or Bloody Church by the local populace, stands as a unique testament to Byzantium’s enduring legacy.

It is the singular domed church in Istanbul that has not only survived the tumultuous centuries since the Byzantine era but continues to serve its original purpose as a place of worship. Its narrative, rich with imperial ambitions, diplomatic maneuvering, and poignant personal stories, truly distinguishes it.

The site’s sacred origins trace back to the early 7th century when Princess Sopatra, daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Maurice, and her companion Eustolia, established a monastery upon the city’s fifth hill. However, the upheaval following the Fourth Crusade and the subsequent Latin Empire led to the monastery’s destruction. As the Orthodox Byzantines reclaimed their city in 1261, a new chapter began. Amidst growing concerns about the Mongol incursions into Anatolia, Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos orchestrated a strategic alliance.

In 1281, he dispatched his illegitimate daughter, Maria Despina Palaiologina, as a bride to the powerful Mongol Ilkhan Hulagu, accompanied by a substantial dowry and an array of opulent gifts. This diplomatic marriage was a pragmatic response to the weakened Byzantine state, which had been significantly depleted of its military and financial resources during the Venetian occupation. The logic was clear: forge kinship with a formidable adversary to deter further aggression.

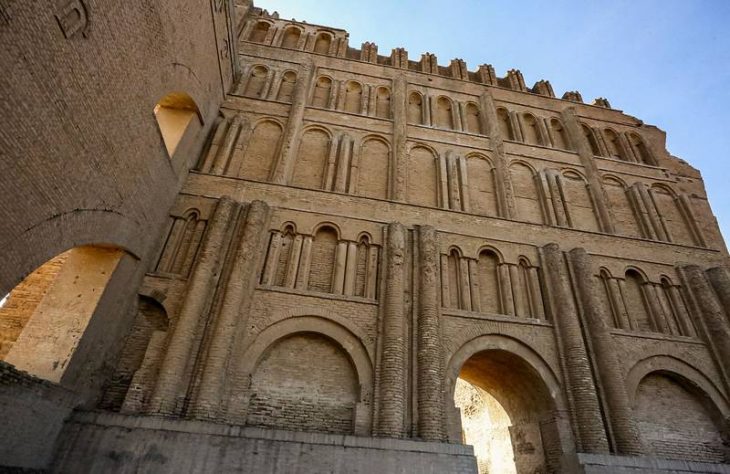

However, fate intervened. Before Maria reached her intended groom, Hulagu Khan passed away, and his capable thirty-year-old son, Abaka Khan, ascended to the Ilkhanate throne. Upon her arrival in Maragheh, the Mongol capital (located in present-day Iran) in the late spring of 1265, Abaka chose to include Maria in his harem and subsequently married her. A devout Christian, Maria requested that Abaka be baptized, a wish he honored. Thus, she became “Khatun Hanim” – the esteemed title bestowed upon her by the Mongols – their queen. After seventeen years of marriage, marked by cultural exchange and perhaps a degree of influence, Maria’s life took another turn with Abaka’s death.

She resolved to return to Constantinople and dedicate the remainder of her years to a monastic life. Upon her return, she acquired the hill where the former church stood, along with the surrounding land, and founded the monastery that now houses the Kanlı Kilise. Embracing the monastic vows fulfilled a long-held aspiration, echoing the life of Saint Melania the Younger, who also faced a forced marriage before pursuing her spiritual calling. Maria took the name of this saint and spent her remaining years in pious devotion on the very hill she had chosen.

Consequently, the church became known as Panaghia Muchliótissa, with “Muchliótissa” signifying “of the Mongols” in Greek. Following the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Fener district, in particular, reportedly witnessed fierce clashes during the three days of plunder sanctioned by Sultan Mehmed II. The steep incline leading to the church became a scene of intense bloodshed, with the crimson flow said to have reached the waters of the Golden Horn, thus giving rise to the evocative name “Kanlı Kilise,” or Bloody Church. While some attribute this name to the memory of the Mongol presence, the striking red-tiled roof of the church likely also contributed to this vivid moniker.

Remarkably, within a century after the Fall of Constantinople, nearly all domed churches in the city were converted into mosques, symbols of the new Islamic sovereignty. Yet, the Kanlı Kilise stands alone as the only domed church to have retained its Christian identity and continues to function as a church to this day. This extraordinary preservation is attributed to a firman, an imperial decree, issued by Sultan Mehmed II,also known as Muhammed bin Murad, Mehmed the Conqueror, and Fatih Sultan Mehmed, himself.

Legend has it that Cristodulos, the Greek architect who designed the Sultan’s grand Fatih Mosque, interceded on behalf of his mother, to whom the church was subsequently gifted. The firman explicitly exempted the church from conversion, a testament to either the Sultan’s respect for the architect or perhaps a strategic move to maintain a degree of goodwill within the local Greek community. This historic decree remains proudly displayed within the church walls, a tangible link to the city’s complex past. In subsequent centuries, despite occasional aspirations to transform it into a mosque, the weight of Ottoman tradition and the enduring power of Fatih’s decree consistently thwarted such attempts.

Today, the legacy of Maria Palaiologina, the “Mary of the Mongols,” lives on not only through her church but also in a poignant depiction within the Kariye (Chora) Church. In the magnificent Deesis mosaic, this remarkable yet perhaps tragic figure is portrayed at the feet of Christ Pantocrator, humbly interceding on behalf of humanity – a lasting image of her journey from Byzantine princess to Mongol queen and ultimately, a revered monastic figure in her restored homeland.

Located in the Fener neighborhood of Istanbul’s Fatih district, this historic church stands on Tevkii Cafer Mektebi Sokak, at the top of a slope with a view overlooking the Golden Horn. It is situated near the impressive building of the Phanar Greek Orthodox College and is enclosed behind a high wall. Although the church doors are usually closed, it is open to the public. Visitors who wish to enter should ring the doorbell located near the entrance.