Archaeologists believe they have found the site where Emperor Otto I (936-973), known as the Great, founder of the Holy Roman Empire, died.

Otto the Great is regarded by historians as the first Holy Roman Emperor. He earned a reputation as a defender of Christendom as a result of his victory over pagan Hungarian invaders in 955 C.E. He used his self-proclaimed divine right as a ruler and his dealings with bishops to tighten his control over his kingdom and to begin his aggressive expansion into Italy. His son Otto II would succeed him after his death in 973 C.E.

Archaeologists from the Saxony-Anhalt State Office for Monument Preservation and Archeology have been excavating the former imperial palace and the rich Benedictine monastery in Memleben, Germany, since 2017.

This year’s investigations yielded new findings of extraordinary importance. For the first time, reliable archaeological evidence of the Palatinate of Memleben, the as-yet unlocated place of death of Emperor Otto the Great and his father Heinrich I, was identified in the form of a stone predecessor of Otto II’s monastery church. A mysterious foundation in the cloister of the monumental monastery church can possibly be linked to the mention of a subsequent burial of Otto the Great’s intestines.

Recent research focused on three areas directly adjacent to the monumental church of Otto II: the area around the northeast side apse, which is partly used as a cemetery, the cloister area at the northern aisle and the connection between the side aisle and the cloister on the western transept.

The former Memleben monastery is one of the most important sites on the Romanesque Road. The ruins of the monastery church from the 13th century with its preserved crypt are considered an outstanding building that documents the transition from the late Romanesque to the early Gothic style. It reflects the historical significance of the place: The founder of the Holy Roman Empire, Emperor Otto I, known as the Great, passed away in Memleben in 973, as did his father Heinrich I in 936.

The son and successor of Otto the Great, Otto II, and his wife Theophanu founded a richly furnished Benedictine monastery in honor of the emperor at his place of death. It was first mentioned in 979 and was one of the most important monasteries in the Ottonian Empire. Although the complex lost its independence as early as 1015 when Heinrich II placed it under the control of the East Hesse Benedictine monastery of Hersfeld, it did not lose its function as a place of remembrance of the ruling family.

In 2022, the remains of the foundations of a stone structure that existed before the church was built were found directly next to the northern side apse of the monumental church of Otto II. Since this was the first indication of architecture that existed before the construction of the monumental basilica and thus dates back to the times of Heinrich I and Otto the Great, its study was of particular importance during this year’s excavations. The previously unknown building could be traced on a larger scale and turned out to be approximately east-west oriented. The interior is about 9.20 meters wide. The extent to the east has not yet been recorded, as the end of the building is superposed here by today’s monastery garden. In addition to clearly defined foundation pits with traces of mortared quarry stone masonry, the west side has an opening over five meters wide. A remnant of masonry in the middle of the opening suggests that it originally had two portals.

The demolished remains of the building are cut by the significantly deeper foundations of the northeast apse of the monumental church. It must therefore be a building preceding the church from the 10th/11th century. Its interior has a massive rubble pavement, which served as a substructure for a lime plaster floor that is only preserved in small parts. The extraordinary quality of the building from the 10th century leads to the conclusion that it is either an older sacred building or an important, representative building of the Palatinate of Memleben. Regardless of the clarification of this question, which can be done in the future with the help of the evaluation of the skeletal material from the adjacent cemetery and further geophysical investigations, it has been possible for the first time to find archaeological evidence of the authentic place of residence and death of the rulers Heinrich I. and Otto I.

A mysterious foundation in the cloister – on the trail of Otto I’s heart?

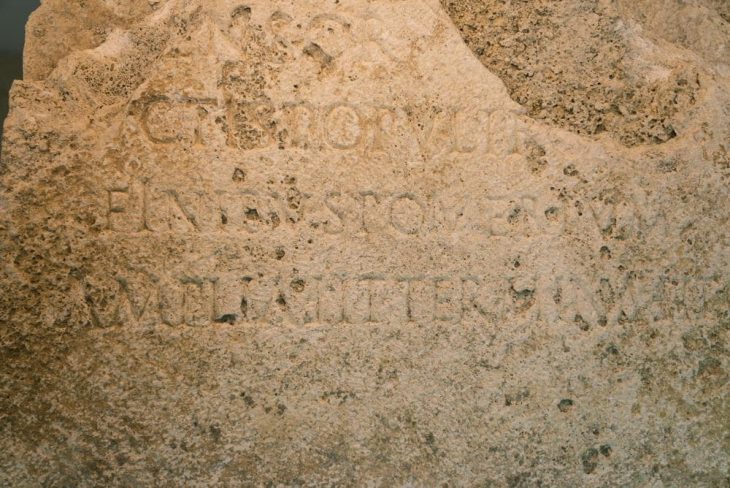

On the northern aisle of the monumental church, the foundation ditch of the original, much bigger cloister from the 10th/11th century could be found under the remains of late medieval modifications. The alignment of the building is interrupted in the center of the cloister by a large pit created to remove building materials. The intention behind this pit is made clear by the preserved substructure of a west-east oriented long rectangular foundation that is deeper than the church nave and by an elaborately worked stone. In the extraction pit above the natural gravel of the Unstrut meadow, a large amount of ceramic and oven tile fragments from a subsequent filling with building rubble were found. In addition to the remains of high-quality glass vessels, a Thuringian hollow penny of Jena mint was found on its sole, which dates the recovery of high-quality parts of the previously completely unknown building, which originally rose on the long rectangular foundation, to the late 14th century.

Based on current knowledge, it remains unclear what the building in the center of the cloister is. It is currently without comparison. However, the traces of the mysterious building evoke associations with a written source from the 16th century, according to which the reburial of Otto the Great’s heart was located in the cloister area. According to Thietmar von Merseburg’s chronicle from the beginning of the 11th century, the ruler’s entrails were buried the night after his death in Memleben’s St. Mary’s Church (a predecessor of Otto II’s monumental church), and his embalmed body was transported to Magdeburg. An interpretation of the newly discovered building in the monumental church cloister as a sanctuary for the temporary storage and veneration of the ‘relic’ with the entrails of Otto the Great is within the realm of possibility. An interpretation as the remains of a tumba (tomb) of a high-ranking personality is also conceivable.

New insights into the construction and end of Otto II’s monumental church

To further clarify the floor plan and the building history of Otto II’s church, an area on the outside of the northern aisle was also examined. This provided insights into the western transept, the foundation of which is interlocked with the nave to the east. This information complements previous findings on the construction sequence: the eastern apse and eastern transept appear to be the first components built. These were supplemented by the two eastern side apses and the nave and western transept, which were built in one go. During the excavation, severe fire traces were also evident on the foundation, which was originally located underground. They can only be explained by a targeted uncovering and burning during the demolition of the building and give an impression of how material was extracted from the enormous structure: the laborious dismantling of individual stones using scaffolding was avoided, but large parts of the masonry were brought to collapse by fire. In parallel with the extraction pit in the cloister area, the demolition can be placed in the 14th century.

In summary, this year’s archaeological excavations in Memleben produced important results. Of particular importance is the evidence of a stone-built predecessor of the well-known church of Otto II, which was of exceptionally high quality and almost monumental by the standards of the 10th century. This discovery is extremely significant, especially in view of the fact that, despite all efforts, the Palatinate Memleben had not been located so far. The palatinate had an enormous historical significance for the founding of the Holy Roman Empire as the royal court and the place of death of the rulers Heinrich I and Otto I, which extends far beyond the borders of Saxony-Anhalt. As part of current research, it has now been possible for the first time to identify reliable archaeological evidence of the authentic location of the palatinate.

The field school and research excavation (August 21st to September 29th, 2023) of the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt (LDA), which has been running since 2017, is conducted in cooperation with the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (MLU), the Anhalt University of Applied Sciences (HA) and has been supported by the Kloster und Kaiserpfalz Memleben Stiftung.

State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt

Cover Photo: State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt