Archaeologists map Red Lily Lagoon, a hidden landscape in the Northern Territory where the first Australians lived more than 60,000 years ago.

Red Lily Lagoon in West Arnhem Land sits more than 40 kilometers inland, near a culturally significant rock art site, Madjedbebe. It is an important archaeological landscape with significant implications for understanding the First Australians.

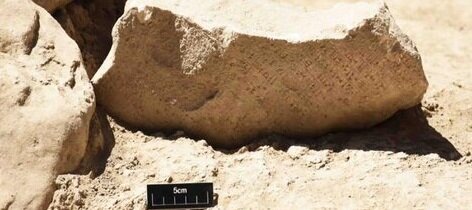

Scientists at Flinders University have used sub-surface imaging and aerial surveys to see through floodplains in the Red Lily Lagoon area of West Arnhem Land in Northern Australia. These ground-breaking methods showed how this important landscape in the Northern Territory was altered as sea levels rose about 8,000 years ago.

The researchers used a 3D model to visualize that landscape, with the findings, published in the scientific journal Plos One.

“These results show huge hidden sandstone escarpments — similar to the dramatic sandstone escarpments we see in Arnhem Land and Kakadu today — that for the majority of human occupation were actually exposed and probably habited by people,” lead researcher Jarrad Kowlessar said.

He said the underground mapping and visualisation technique could be used by archaeologists to identify underground sites where First Australians may have lived thousands of years ago, and potentially left behind rock art or tools.

The findings also provide a new perspective on the region’s rock art, which is internationally recognized for its significance and distinct style.

The researchers can see how the transformation of Red Lily Lagoon had led to the growth of mangroves that have supported animal and marine life in a region where ancient Indigenous rock art is located by examining how sediments now buried beneath the flood plains changed as sea levels rose. This transformation has, in turn, fostered an environment that has inspired the subjects and animals in ancient rock art.

In their findings published, the researchers say environmental changes at the lagoon are reflected in the rock art because fish, crocodiles, and birds were featured in the art when the floodplain transformed to support freshwater habitats for new species.

The study’s co-author, Associate Professor Ian Moffat, said the technique was a “game changer” for archaeological research.

“Instead of focusing on the archaeological sites — which is the way we normally think about archaeology — we’ve really stepped out and tried to understand the landscape in a much more holistic way,” he said.

Professor Paul Tacon, an archaeologist at Griffith University who was not involved in the research, said the technique was a “promising” use of the 3D modeling technology, but more research was needed.

Professor Paul Tacon also warned that if rock art had been painted on the sandstone cliffs, it would likely have been eroded by now.

Dr. Kowlessar, however, thinks that even if rock art had been lost to time, the method could still be used to locate locations where people may have left behind tools, furthering researchers’ understanding of Australia’s First Peoples.