Using drone mapping, an academic from Cranfield University in the UK has revealed that Dmanisis Gora, a 3,000-year-old mountainside fortress in the Caucasus Mountains, is much larger than previously thought.

Among the first of its kind in this region of Eurasia, Dmanisis Gore, which is inside the boundaries of the Republic of Georgia, has long been regarded as a significant Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age settlement.

Dr Nathaniel Erb-Satullo, Senior Lecturer in Archaeological Science at Cranfield Forensic Institute, has been researching the site since 2018 with Dimitri Jachvliani, his co-director from the Georgian National Museum, revealing details that re-shape our understanding of the site and contribute to a global reassessment of ancient settlement growth and urbanism.

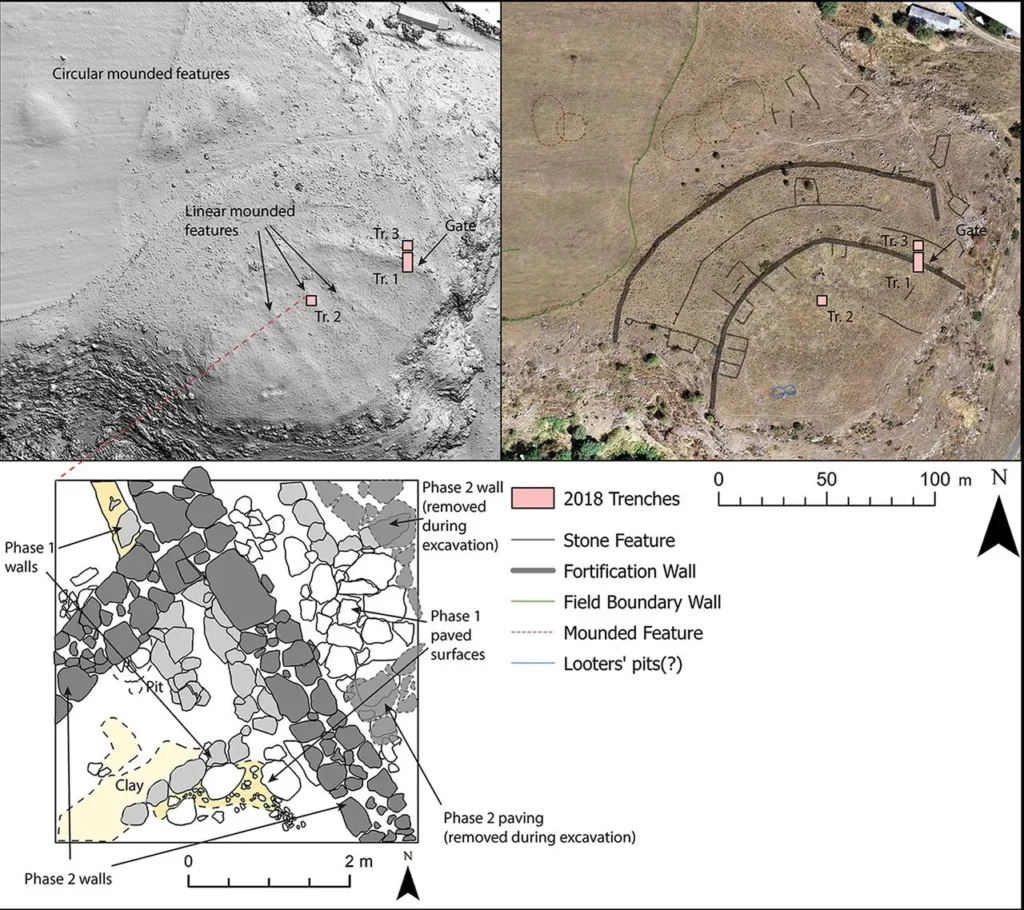

Research on the fortress – named Dmanisis Gora – began with test excavations on a fortified promontory between two deep gorges. A subsequent visit in Autumn, when the knee-high high summer grasses had died back, revealed that the site was much larger than originally thought. Scattered across a huge area outside the inner fortress were the remains of additional fortification walls and other stone structures. Because of its size, it was impossible to get a sense of the site as a whole from the ground, prompting the use of advanced drone technology to create aerial imagery.

“The drone took nearly 11,000 pictures, which were processed using specialized software to produce high-resolution digital elevation models and orthophotos,” Dr. Erb-Satullo explained. “These datasets allowed us to identify subtle topographic features and create precise maps of fortification walls, graves, field systems, and other structures within the outer settlement.”

The drone survey showed that the fort is expansive, with its outer settlement protected by a fortification wall that stretches a kilometer long. This makes Dmanisis Gora more than 40 times the size initially estimated.

The research team used a DJI Phantom 4 RTK drone which can provide relative positional accuracy of under 2cm as well as extremely high-resolution aerial imagery. In order to obtain a highly accurate map of human-made features, the team carefully checked each feature in the aerial imagery to confirm its identification.

The researchers merged aerial photographs with declassified Cold War–era spy satellite images to identify ancient structures from recent modifications attributable to the advent of modern farming. That gave researchers much-needed insight into which features were recent, and which were older. It also enabled researchers to assess what areas of the ancient settlement were damaged by modern agriculture. All of those data sets were merged in Geographic Information System (GIS) software, helping to identify patterns and changes in the landscape.

The massive size and defensive architecture of the site suggest that it was a major settlement in an era of evolving social and political complexity in the region.

The authors note that the data from Dmanisis Gora supports theories that pastoral mobility was still a major element of Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age cultures in the Caucasus region, meaning the people remained on the move much of the time even though they constructed facilities that would suggest they were getting ready to urbanize in a major way.

The site exhibits evidence of low-intensity occupation, which may indicate seasonal use, despite the significant investment in stone architecture. This lends credence to ideas that pastoral mobility was still significant in Late Bronze and Early Iron Age societies.

This work has been funded by the Gerda Henkel Foundation, the Gerald Averay Wainwright Fund and the British Institute at Ankara.

Cover Credit: N. L. Erb-Satullo et al., Antiquity (2025)